Until about 20 years ago, little was known about the abundance of colorful cold-water corals that line sections of the seafloor around Alaska.

Now an environmental group has gone to court to try to compel better protections for those once-secret gardens.

The lawsuit, filed Monday by Oceana in U.S. District Court in Anchorage, accused federal fishery managers of neglecting to safeguard Gulf of Alaska corals, and the sponges that are often found with them, from damages wreaked by bottom trawling.

Bottom trawling is a practice that harvests fish with nets pulled across the seafloor.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service “ignored important obligations” to protect the Gulf of Alaska’s seafloor, under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, the lawsuit said.

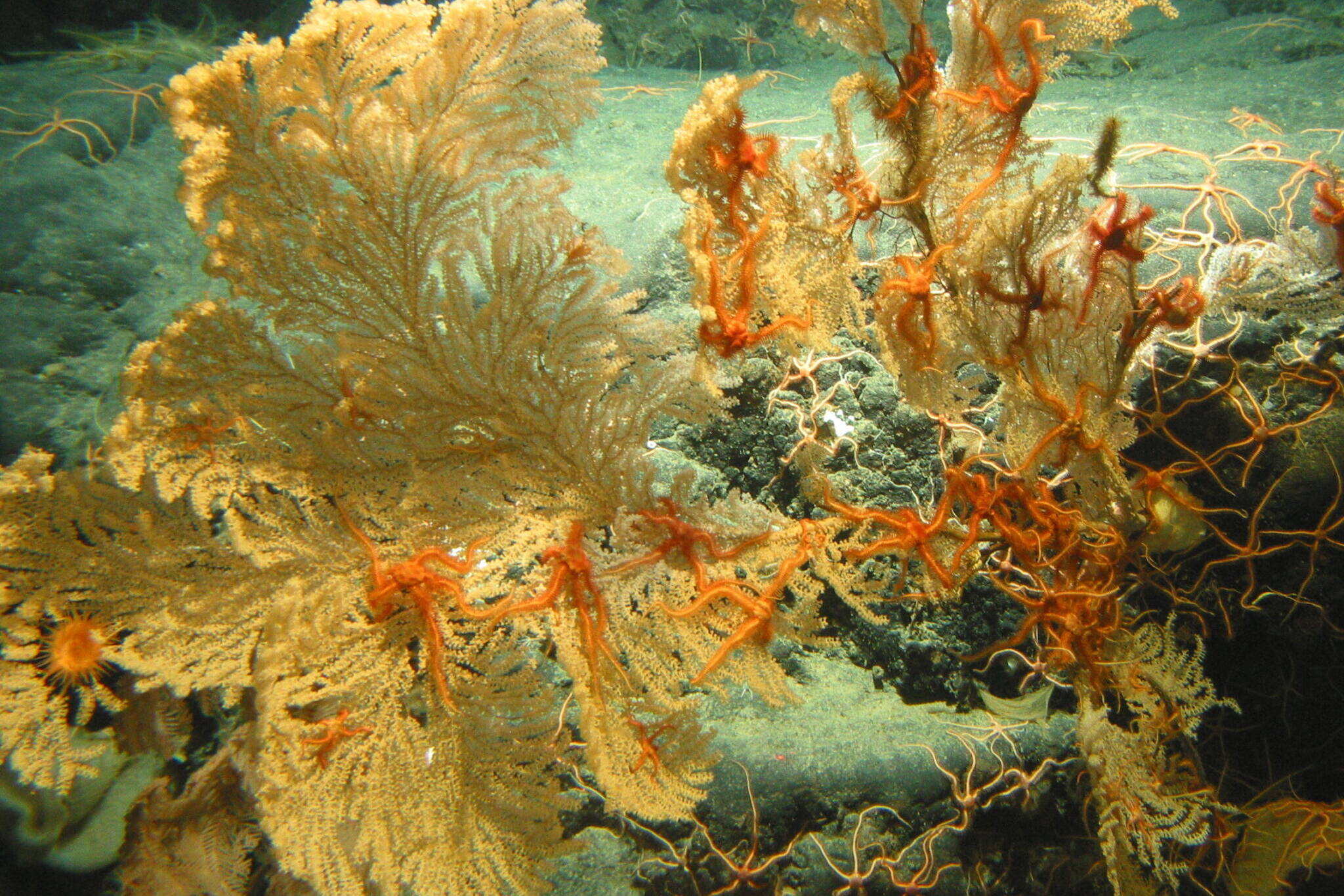

Corals and sponges are important marine habitat features, supporting fish populations and other sea life. Already vulnerable to the warming conditions caused by climate change and acidification caused by the ocean’s absorption of atmospheric carbon, corals and sponges are further imperiled by fishing gear that scrapes the seafloor, the lawsuit said.

“If not destroyed by trawling, some corals and sponges can live for hundreds or thousands of years. They provide complex habitat for fish and other species, including commercially important species like rockfish, crab, and prawns,” the lawsuit said. “Damage to long-lived, slow-growing, and sedentary species, like cold-water corals and sponges, can be irreversible.”

At issue in the lawsuit is the way managers identify and protect what is known as “essential fish habitat.”

The North Pacific Fishery Management Council, which sets policies that are carried out by the National Marine Fisheries Service, does periodic reviews to determine which areas should be considered essential fish habitat and what special protections should apply there. In December, the council passed a series of updates for habitat important to a variety of fish species; those changes got NMFS approval in July.

But a key omission from those updates are any new protections for coral gardens or sponge habitat in the Gulf of Alaska, Oceana argues.

That leaves the swath of Gulf water that stretches from Yakutat to the Islands of the Four Mountains in the Aleutians as “the largest remaining area between San Diego and the Arctic that is largely open to bottom trawling,” said Ben Enticknap, Oceana’s Pacific campaign director and senior scientist.

More knowledge is being gained about Alaska’s corals and sponges and their role in the ecosystem, Enticknap said. “That type of information is really critical and should be incorporated into the council’s process for consideration,” he said.

At the June 2023 North Pacific Fishery Management Council meeting, Oceana submitted a proposal that would close about 90% of the Gulf to bottom trawling. The council did not take any action on that proposal, Enticknap said.

In the past, the council was a pioneer in cold-water coral protection, Enticknap said.

In 2005, the council closed a large marine area around the Aleutians to bottom trawling to protect the coral gardens that had been newly discovered there. Enticknap, then with the Alaska Marine Conservation Council, provided information that helped bring about what he considers to be a landmark policy change.

The 2005 rule did close some sections of the Gulf of Alaska to bottom trawling for the purpose of coral protections. But Oceana contends that much more area should be off-limits to bottom trawling.

A spokesperson for NMFS declined to comment on the lawsuit, citing the agency’s policy concerning pending litigation.

The agency itself is the prime source of new knowledge about Alaska’s corals and sponges.

NOAA scientists have been working for several years to identify and map Alaska’s corals, including those on the floor of the Gulf of Alaska. Underwater surveys, including those conducted last summer by NMFS in collaboration with an array of international agencies and institutions, have used sophisticated technology to capture images of the corals, sponges and the sea creatures that live among them. An important goal of the research, according to NMFS, is examining whether fishing, other human activities or climate change are harming the coral habitat and, if so, how that habitat should be protected.

The Oceana lawsuit is not the only effort to secure more protection for deep-water corals.

A bill sponsored by U.S. Rep. Mary Peltola, D-Alaska, seeks to restrict trawl fishing that touches the seafloor. Called the Bottom Trawl Clarity Act, it specifically lists corals and sponges as resources to be protected from trawling impacts.

• Yereth Rosen came to Alaska in 1987 to work for the Anchorage Times. She has reported for Reuters, for the Alaska Dispatch News, for Arctic Today and for other organizations. She covers environmental issues, energy, climate change, natural resources, economic and business news, health, science and Arctic concerns. This article originally appeared online at alaskabeacon.com. Alaska Beacon, an affiliate of States Newsroom, is an independent, nonpartisan news organization focused on connecting Alaskans to their state government.