KENAI — Juniper Lanmon-Freeman cried the first time she attended the birth of a child. A licensed midwife, Lanmon-Freeman now delivers two to three babies per month for mothers at their homes. But the job goes far beyond that — by the time she delivers the child, she’s spent weeks with the mother.

“(On) my last birth, I visited her 13 times before she had her baby,” she said. “When they’re in labor, you’ve built this relationship with them. It’s more like a sister relationship or a good female friend.”

Lanmon-Freeman is one of just 63 licensed midwives in Alaska, and one of two on the central Kenai Peninsula. Three more are licensed in Homer, and the majority practice in Anchorage. Sometimes, when she’s attending a birth and another one of her clients goes into labor, the peninsula’s midwives will step in for each other, Lanmon-Freeman said.

“We have an agreement that if (a mother goes into labor) and you’re at another birth and you can’t go, (we’ll cover each other),” she said. “We’ve got some grey hairs out of it.”

However, next year, the picture will likely change. The cost to obtain a direct-entry midwife license — a license to practice as a midwife primarily in out-of-hospital settings — in Alaska will more than double, rising from $1,750 to $3,800 for a biennial certification. That doesn’t include the initial application fee and the fees for certifications for apprenticeships, which midwives have to complete before becoming eligible for full certification.

For morticians, the fee is increasing from $100 to $150 every two years. For naturopaths, license applications fees are increasing by a factor of 10 from $50 to $500, and a biennial license will cost $1,200 instead of the former $470. It doesn’t include all the licenses. For some, fees are actually going down. For example, behavioral analysts will only have to pay $500 for their licenses next year instead of $1,000.

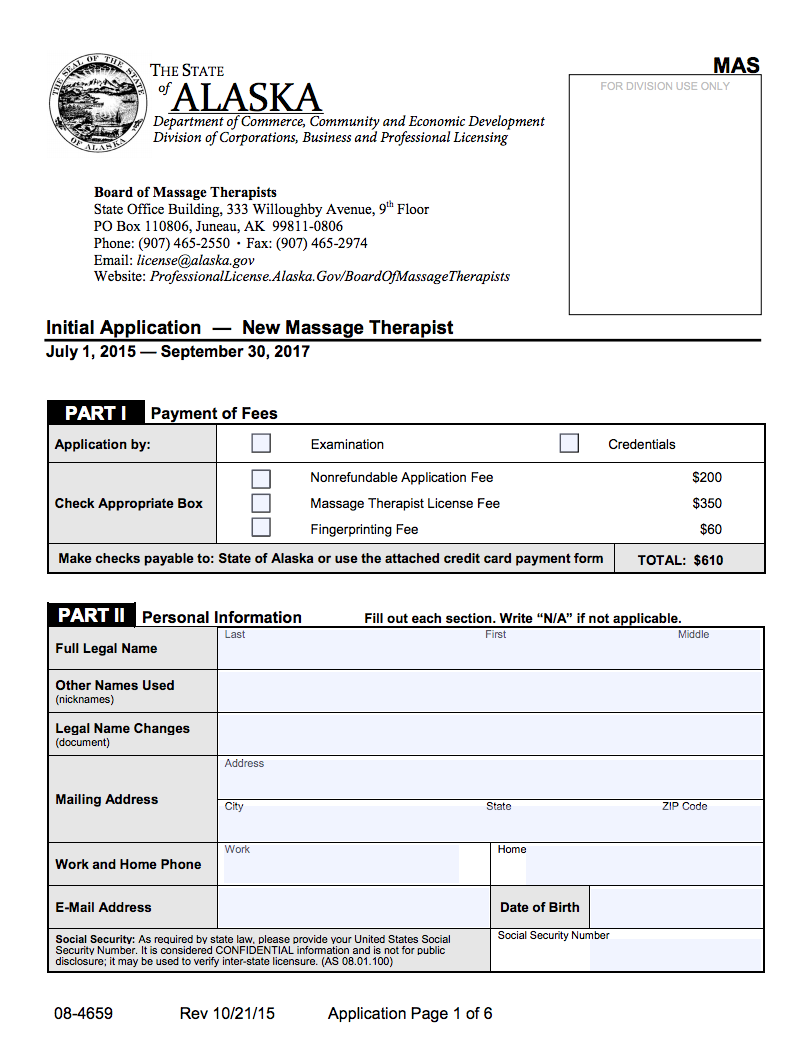

The state of Alaska requires occupational licenses for a variety of professions, from doctors to underground storage tank workers to pawnbrokers. Each of those licenses has to be renewed with the state every two years for the professional to legally work. It’s not a set list — the Legislature can add a licensing requirement for occupations at any time, as in the case of massage therapists, who were not required to be licensed until 2015.

The Alaska Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development administers licenses through its Division of Corporations, Business and Professional Licensing. Boards such as the Medical Board or the Board of Direct-Entry Midwives manage many of the programs, but those that aren’t are administered directly by the division.

Alaska statute requires every occupational licensing program to balance its operating fees with the revenue from professional licenses. The division staff evaluates the fees every year to determine if they have to increase or if they can decrease them to stay solvent, said Sara Chambers, division operations manager.

“That sounds like a pretty straightforward business practice,” Chambers said. “… Fee programs may or may not be changed. We will often change fees before renewal. It makes a lot more sense to put a new fee in place in advance (of renewals).”

The licensing programs don’t rely on the state general fund to operate, so it isn’t the state budget deficit that’s pushing the fees up — it’s increasing investigation and legal fees and imbalances between the operating and licensing costs.

“Part of our cost is hearing costs,” said Angela Birt, who oversees the investigations in the division. “We’re represented by the Department of Law … a lot of the cost you see about investigations are typically related to legal proceedings.”

Last year, the division conducted 600 investigations, according to a July 2016 report to the Legislature. Investigations can range in complexity, taking years in some cases. The complexity pushes up the cost. But the person being investigated doesn’t pay for the investigation — that’s borne by the program. Fines paid as the result of investigations go back to the state’s general fund, Chambers said.

As a result, the staff that works on the investigations keeps tight timesheets.

“Generally, they’re trying to count down to the quarter of the hour,” Birt said.

Chambers said there had been some concerns raised over the years about the way the licensees bear the cost while the fines go to the general fund.

“That’s been a concern that the good apples are essentially paying for the bad apples,” Chambers said. “We’ve worked on it different ways, different times throughout the years.”

Rep. Kurt Olson, R-Soldotna, the outgoing representative for the central Kenai Peninsula, proposed a bill in April 2013 at the request of the Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development “to levelize the dramatic changes in professional licensing fees,” according to the minutes from the House Finance Committee in April 2014. The bill would have changed that law to fund the personnel costs for investigations out of the general fund instead of licensing fees.

The Alaska Nurses Association testified in opposition to the move, expressing concerns about additional pressure on the general fund in a time of declining revenues. Patricia Senner, who testified to the House Finance Committee on behalf of the association, said the association instead suggested the Legislature set up a fund to deal with the most expensive investigations rather than all of them.

“From a historical perspective, the decision to have licensee fees pay for the cost of the Boards was made during a time of diminishing state revenues,” Senner said in her testimony. “We do not think over the next several years the Division is going to want to be reliant on a diminishing source of general fund revenues when they could have had a more steady income source with licensee fees. If the Division can’t get enough general funds to pay for their investigators, how are they going to prioritize investigations?”

The bill was last heard and held in the House Finance Committee in April 2014, according to the Alaska State Legislature’s website.

Lanmon-Freeman said she runs her business on a fairly tight margin. She accepts Medicaid and Denali KidCare, both of which pay lower reimbursement rates than private insurers. She also charges between $6,000 and $10,000 for a birth, which includes the prenatal and post-natal visits, she said.

A study published July 2015 in the trade journal Health Affairs found that hospital costs for low-risk childbirth varied widely among facilities in 2011. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the national average covered cost in 2013 was about $13,118 for a delivery without complications. In Alaska, that same procedure cost about $15,477 in 2013, according to CMS.

However, that doesn’t include the cost of pre- and post-natal care, medications, travel or the additional costs incurred by complications. CMS did not publish data for Alaska on costs for a C-section without complications, but nationally the average is $20,179, according to the CMS data. Alaska tends to be more expensive than the national average for health care procedures.

Midwives are able to offer more personal care without the risk of hospital-acquired infections or travel, Lanmon-Freeman said. In the end, for many mothers on Medicaid or Denali KidCare who use midwives, the relatively controlled costs and low risk of complication save the state money in the long run, but the increase in licensing fees threatens their ability to keep prices low, she said.

“It’s pushing a lot of midwives into a predicament: do you continue practicing something that you love, that your clients love, but can you afford it?” Lanmon-Freeman said. “… You just do it for the love of it.”

She said she was concerned that as the fees continue to increase, it may drive more midwives to not reapply, increasing the pressure on the remaining midwives in the program to bear the cost of licensing and regulation, pushing fees even higher.

Division of Corporations, Business and Professional Licensing Director Janey Hovenden said in testimony to the Legislature in January 2016 that one of the challenges of setting fees is to set up a path to get programs out of an operating deficit while not pricing people out of the occupation. Auditors have suggested some fixes for such a problem, such as combining the midwife licensing program with the nursing licensing program, which has approximately 16,000 licensees, Birt said.

To anticipate costs, the division developed a cost prediction tool that is essentially a spreadsheet that allows managers to test different license costs and project the effect on the program’s bottom line in the future. The future is hard to predict because the number of licensees is always uncertain, Chambers said. Program fees pitch up and down over the years as the division corrects deficits and works to reduce surpluses.

“If there’s a spike in investigations, that may cost (a particular) program a little more money in the next cycle,” she said. “The tool gives us a consistent and transparent way to estimate those. At the end of the day, it is an estimate.”

Elizabeth Earl is a reporter for the Peninsula Clarion. She can be reached at elizabeth.earl@peninsulaclarion.com.