IDOMENI, Greece — At flashpoints near borders on either side of Europe, authorities tried Tuesday to force back migrants desperate to begin new lives in more prosperous nations.

In Greece, police bused about 1,250 Afghans stuck at the Macedonian border back to Athens after countries further up the migrant trail wouldn’t let them through. In France, authorities prepared to evict people from a shantytown known as the “jungle” in the port of Calais, where migrants wait for a chance to try to cross into Britain.

The seemingly arbitrary decision by some Balkan countries to close their borders to Afghans attempting to make their way across Europe to seek asylum has left thousands stranded in Greece, even as more continue to arrive on Greek islands from the nearby Turkish shore.

By nightfall, more than 4,000 people, mostly from Syria and Iraq, were camped out just yards from the border fence waiting to cross into Macedonia. Although those nationalities were not being blocked, the flow across the border had slowed to a trickle, leaving thousands waiting in the cold as night descended.

The European Union and United Nations criticized the new restrictions on Afghans, with the EU’s executive arm saying it had “concerns about this approach” and would raise the issue with the countries in question.

Among the Afghans turned away from the Macedonian border was 20-year-old Mirwais Amin, who said he was separated from relatives when he was sent back to Athens.

“Macedonia isn’t letting migrants through. I can’t understand why,” he said. “I can’t get to the (border) camp, and members of my family are there. It’s cold here and we have no food.”

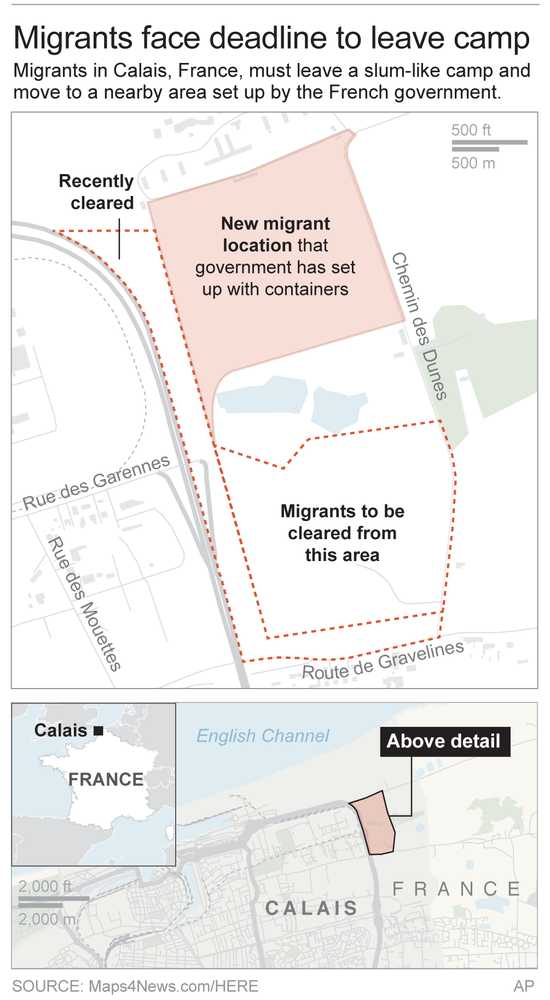

In Calais, authorities maintained the sprawling shantytown, which cropped up years ago but mushroomed last year in the midst of the migrant crisis, is a sanitation risk. Charity groups went to court to seek a last-minute delay of the forced evacuation, and on Tuesday the court announced a decision would not come until Wednesday or later.

Officials estimate 800 to 1,000 people live on the muddy, makeshift site, but humanitarian groups contend the figure is more than 3,000.

Regional administration head Fabienne Buccio said on Europe-1 radio the expulsion order doesn’t mean authorities will use force. Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve insisted the evacuation would be “progressive.”

Maya Konforti of the aid group L’Auberge des Migrants said volunteers would stand by the migrants if authorities try to force them out.

“We are going to be at their side … no matter what,” she said. “We are very suspicious but we are hopeful that they are going to be reasonable, because we are reasonable.”

Belgium was reinforcing its borders with France near Calais in anticipation of a potential wave of people attempting to cross if the camp is shut down.

The waves of refugees heading to Europe have grown in pace even compared to last year’s massive influx, sorely testing European unity. Greece, with its extensive coastline and its islands’ proximity to Turkey, is by far the favored route.

On Tuesday, the International Organization for Migration said more than 102,500 people had crossed into Greece since Jan. 1 and another 7,500 streamed into Italy over the same period. Such figures weren’t reached last year until June. More than 1 million people crossed into Europe in 2015, more than 80 percent of them reaching Greek islands from Turkey.

Despite initial welcoming overtures from some more prosperous European countries such as Germany, the sheer size of the flow has made nations balk at the prospect of having to integrate so many new arrivals.

Several countries have been distinctly hostile to the idea, and those along a route that migrants take through the Balkans in hopes of reaching countries like Germany and Sweden have closed their borders to certain nationalities. The latest move was against Afghans, who were not allowed to cross from Greece into Macedonia this week, leading to protests on the border and the danger of thousands being stranded in the financially troubled country.

Greece on Tuesday slammed Austria for drastically restricting the crossings of asylum-seekers and for inviting officials from western Balkan countries to discuss the migration issue while excluding Greece.

The Greek foreign ministry described the gathering in Vienna as a “unilateral move which is not at all friendly toward our country.”

Government spokeswoman Olga Gerovassili said Greece was making plans to house of tens of thousands of migrants. However, she said, Europe should be dealing with the issue cohesively.

“It is not acceptable and it must not be tolerated by the EU, for (some members) to do their own thing, regardless of what everyone agreed on,” she said.

The Austrian cap on the number of people it will admit each day prompted Macedonia to prevent Afghan migrants from crossing last weekend and to slow the rate at which asylum-seekers from Syria and Iraq were allowed to cross.

Faced with the buildup at the Greek-Macedonian border, police early Tuesday ordered mostly Afghan migrants onto Athens-bound buses. They were being taken to an army-built camp near the capital that was set up last week, following European Union pressure to complete screening and temporary housing facilities.

The International Rescue Committee described Macedonia’s restrictions as “yet another example of arbitrary, unilateral decisions by individual states threatening to cause serious humanitarian consequences for desperate refugees.”

Bill Frelick, refugee program director at Human Rights Watch, accused EU countries of turning a blind eye to the plight of Afghan asylum-seekers.

“Once again, Europe is resorting to closing its borders to asylum-seekers, instead of coming up with realistic policies to address the plight of those fleeing war and repression,” he said.

Athens says it is shouldering a disproportionate burden in what is essentially a European refugee crisis even as other EU countries have been painfully slow to fulfill pledges to accept asylum-seekers for relocation.

Frustrated by the slow pace of progress, Greece’s Southern Aegean prefecture signed a bilateral agreement Tuesday with Spain’s regional authority of Valencia for the transfer of at least 1,000 refugees from Aegean islands.

The agreement was signed on the island of Leros, with the Southern Aegean regional authority saying the deal would be sent to the two countries’ governments for ratification.

Under the agreement, Valencia will arrange for a ship with a capacity of 1,000 people to sail from the Aegean islands to Spain, with the possibility of such a journey being repeated.

___

Becatoros reported from Athens. Associated Press writers Derek Gatopoulos in Athens, Elaine Ganley in Paris, Sylejman Kllokoqi and Boris Grdnoski in Gevgelija, Macedonia, and Dusan Stojanovic in Belgrade, Serbia, contributed to this report.

___

Follow Kantouris at http://www.twitter.com/CostasKantouris and Becatoros at http://www.twitter.com/ ElenaBec