Most adult insects have two kinds of eyes.

Small “ocelli” on various parts of the head are light-sensitive but are thought not to make good images. The two large “compound eyes” that are used for finding food or mates or landing sites are actually composed of numerous single light receptors called ommatidia. There are thousands of ommatidia in the compound eyes of some insects, such as dragonflies, but only a few in ants. In day-active insects, each ommatidium typically forms its own image, so what a compound eye sees is a mosaic. A mosaic isn’t as clear as the single image made by a vertebrate eye, but compound eyes are very good at detecting motion.

Day-active insects typically have good color vision, although they have little sensitivity to red. Most of these insects have two peaks of light sensitivity, one in the green-yellow range of wavelengths, the other in blue and ultraviolet. But honeybees, bumblebees and most butterflies generally have three peaks of light sensitivity: for yellow, blue-violet and UV.

[How vertabrates use ultraviolet light]

Many of us are familiar with hummingbirds’ preferences for red. Insect pollinators also have color preferences — bees for blue, hoverflies for yellow. But they are certainly not restricted to those colors and may visit many kinds of flowers, using color as one means of telling them apart, so they can learn to avoid those offering little reward.

Showy flowers with pretty petals and other ornamentation evolved to attract pollinators; they are part of a sexual display, making use of insect color-vision in achieving pollination. The wide array of colors and color patterns of flowers — along with size and shape — helps insects to discriminate among flower species and concentrate their visits on those that offer the best access to food rewards (exceptions include flowers that are false advertisers, as discussed in a previous essay). From the flowering plant’s point of view, concentrating an insect’s visits increases the probability that pollen is transferred among plants of its own species and less is wasted on some other kind of flower, with no reproduction accomplished.

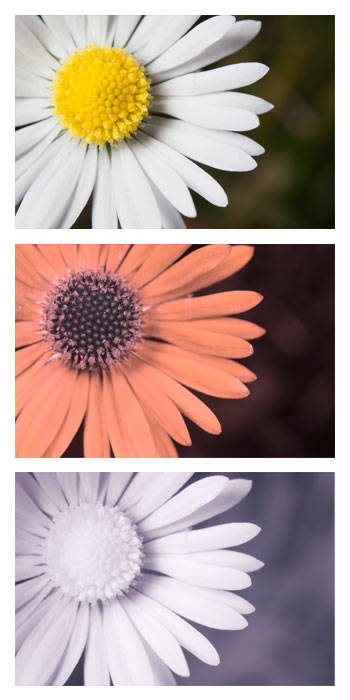

Humans can’t see UV, so flowers look quite different to us than to a bee or butterfly. Some flowers have particular UV markings, which we can “see” only with special equipment, that help identify the flower or perhaps guide an insect visitor to the right place and position to obtain nectar and effect pollination. Here are some local examples:

Silverweed (Potentilla anserina) is common on our wetlands, yellow marsh marigold (Caltha palustris) grows in some sloughs and slow creek and large-leaved avens (Geum macrophyllum) grows along many trails. All three have flowers that are yellow to human eyes. And all three are reported to have flower centers that absorb UV and look dark, in contrast to the outer parts of the petals, which reflect UV and are bright. Many bee-pollinated yellow flowers are said to have this arrangement, with UV absorbing centers and UV-reflecting peripheries.

The blue harebell (Campanula rotundifolia) reflects UV on the female sexual parts (pistil and stigma). Field chickweed (Cerastium arvense) has white flowers that reflect UV strongly. The yellow monkey-flower (Mimulus guttatus) has two different life-histories: some are perennial and some are annual, and the UV markings on their flowers differ too. Bees are reported to discriminate against whichever pattern is unfamiliar to them.

Long-leaf sundew (Drosera longifolia) that grows in some of our muskegs has white flowers. But the petals and sexual parts absorb UV while the nectaries are strongly reflective of UV rays. Interestingly, in this insectivorous plant, which traps bugs on its leaves, the leaf blade absorbs UV but the sticky drops on the bug-catching tentacles have strong UV reflectance, making a big contrast.

[Fantastic spiders use brilliant colors in mating]

Among the orchids, the forest-dwelling species known (for some strange reason) as rattlesnake plantain (Goodyera oblongifolia) has white flowers and is bee-pollinated. But the forward-projecting, cup-shaped middle petal, called the lip, is reported to reflect UV as a bright yellow-green. Yellow ladyslippers (Cypripedium parviflorum) are said to have very UV-reflective tissue around the opening of the lip (or “slipper”), at least in some populations. UV patterns of calypso orchids in Southeast are now being investigated. (Thanks to Marlin Bowles for digging up the information on orchids.)

Some of our non-native flowers have UV patterns too. Dandelions absorb UV in the center and reflect UV on the outer fringe of petals. The little weed called herb robert (Geranium robertianum) has a dark-centered, UV-absorbing pink flower. Orange hawkweed (Hieracium aurantiacum) has orange-red flowers that are said to reflect a checkered pattern.

Many other local species have apparently not been examined for UV-absorbing and -reflecting patterns. There’s a photography project waiting for someone!

Exactly how the UV patterns work in attracting insects or in focusing an insect visitor’s attention on the nectar source and sexual parts of the flower is not well documented, it seems. Insects may sometimes be indifferent to them or attentive only in certain conditions. More research is needed.

• Mary F. Willson is a retired professor of ecology. “On The Trails” is a weekly column that appears every Wednesday.