By Mike Koshmrl

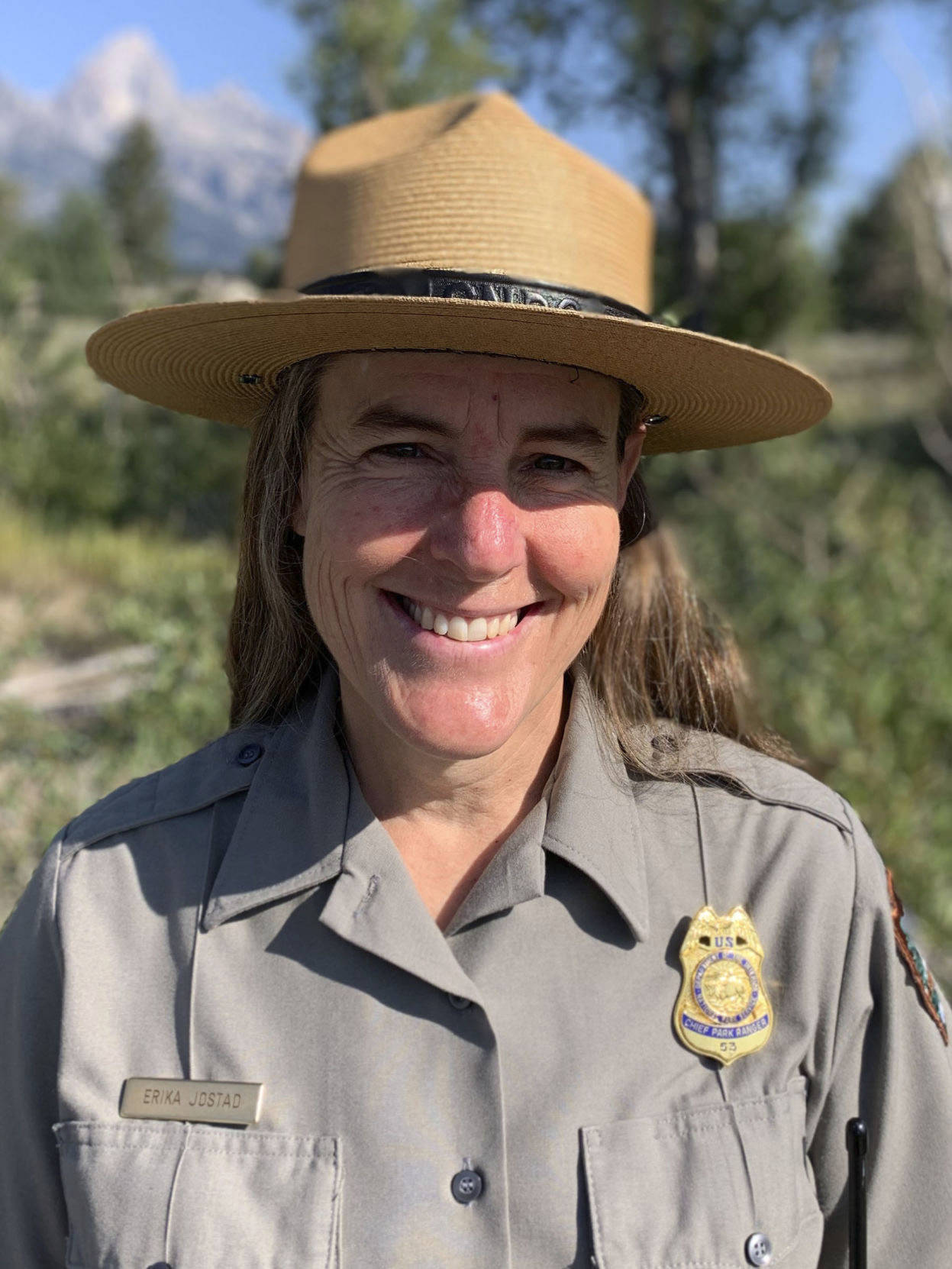

JACKSON, Wyo.— Erika Jostad’s baseline for what Grand Teton National Park is like in the summer is skewed by 2021, easily the busiest year in the park’s 92-year-and-running history.

Teton Park’s incoming permanent chief ranger has been in the job for months on an interim basis, during which time she’s overseen some 60 “incident responses” to fire — and that’s with a couple months of wildfire season remaining. The more general emergency call caseload has ballooned, too, outpacing gains in visitation and increasing nearly 70% over the average from the past five years.

“One of the things I’ve heard a lot about is that more people are coming to national parks, who are maybe not traditional park visitors,” Jostad told the Jackson Hole News&Guide. “It’s wonderful that we’re reaching new audiences and developing their support, but they’re also less experienced with things like camping, hiking, backcountry travel and river travel. And so it’s a possibility that they’re the ones who are more likely to get in trouble.”

The fast-paced, action-packed nature of a job overseeing a ranger corps at one of the five most peopled national parks isn’t something that’s off-putting to Jostad. Rather, there was an allure to the sometimes-hectic duties after a six-year stint as chief ranger at Alaska’s Denali National Park, which is comparatively remote and quiet.

[Not moving at a glacial pace]

“I’m excited to be working in a place that has a little bit more tempo and visitation,” Jostad said. “There are complexities and challenges here.”

Jostad succeeds Michael Nash, who took a position this spring as a national law enforcement specialist with the National Park Service’s Washington, D.C., office. Until his transition, he held Teton park’s top cop post for nearly 11 years.

A California native, Jostad becomes the first female chief ranger in Grand Teton National Park history. It’s an honorific she’s familiar with: In 2016 she became the first female Denali chief ranger.

“Some of what Grand Teton is really thoughtfully trying to do is bring more voices into the park’s employee community,” Jostad said. “Part of that is creating greater gender diversity.”

In her new role Jostad is in charge of personnel — firefighters and law enforcement rangers — who traditionally have been mostly male. That demographic makeup is not surprising, she said, considering the agency’s history.

“The Park Service grew out of the military,” Jostad said. “It’s a white, male organization.”

A 25-year National Park Service veteran, Jostad has a career that includes permanent law enforcement gigs at California’s Kings Canyon and Sequoia national parks and Gates of the Artic National Park and Preserve in Alaska. Factor in seasonal and temporary positions and her career also includes stops at Mount Rainier, Zion and Yosemite national parks, in addition to Glen Canyon and Lake Roosevelt national recreation areas.

Teton Park Superintendent Chip Jenkins praised his new hire in a statement.

“Erika is recognized nationally as an outstanding leader within the National Park Service,” he said. “She is a forward-thinking professional, adept at collaborative relationships, and we are fortunate to have her join our community as a steward of this place.”

Jostad moves to northwest Wyoming with her husband and son and their golden retriever and cat. They’re dwelling in federally owned housing at Moose, which is becoming an increasingly in-demand asset for the Park Service in evermore pricey Jackson Hole. As longtime employees like Michael Nash are leaving, the number of homeowners among the park’s staff is dwindling.

“It’s out of my price range, certainly, to be able to buy something in the community,” Jostad said. “So that means when you replace the chief ranger, you have to have a house in the park for them, too.”

“The number of positions that the park has exceeds, by a fair amount, the number of homes,” she added. “So, we’re on the brink of not being able to actually refill positions.”