SEATTLE — After a massive toxic algae bloom closed lucrative shellfish fisheries off the West Coast last year, scientists are turning to a new tool that could provide an early warning of future problems.

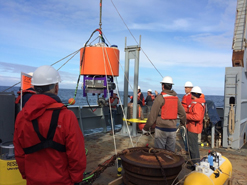

Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Washington last week deployed the so-called ocean robot about 50 feet into waters off the coast of La Push, Washington, near a known hotspot for toxic algae blooms.

The tool, dubbed “a laboratory in a can,” will remain in the water until mid-July, providing real-time measurements about the concentrations of six species of microscopic algae and toxins they produce, including domoic acid.

The instrument is equipped with sensors and cellular modems that will allow it to take water samples and send that information to shore three times a week for the next several weeks. Scientists plan to deploy it again in the fall, another critical time for harmful algae blooms.

Last year, dangerous levels of domoic acid were found in shellfish and prompted California, Washington and Oregon to delay its coastal Dungeness crabbing season. Washington and Oregon also canceled razor clam digs for much of the year.

The domoic acid was produced by microscopic algae that flourished during the summer amid unusually warm Pacific Ocean temperatures. The massive algae bloom produced some of the highest concentrations of domoic acid observed along some parts of the West Coast.

Shellfish managers, public health officials, coastal tribes and others will be able to access the algae data and get advanced warning of toxic algae blooms off the Washington coast before they move to the coastline and contaminate shellfish.

Domoic acid is harmful to people, fish and marine life. It accumulates in shellfish, anchovies and other small fish that eat the algae. Marine mammals and fish-eating birds in turn can get sick from eating the contaminated fish. In people, it can trigger amnesic shellfish poisoning.

Stephanie Moore, a scientist with NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, said the instrument will make it much easier to get crucial information about blooms and toxins sooner.

Researchers typically would have to go out in a boat, collect water samples and bring them back to a lab to be analyzed, a process that could take days, she said.

“We’re actually miniaturizing a lab, putting it in a can and then leaving it out in the field to do the work for us,” Moore said. “This is so great because in so many of these remote offshore locations, we can leave the lab out there and get this information in a matter of hours rather than days.”

The tool, called an environmental sample processor, was developed at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. Dozens of engineers, scientists and others from multiple institutions worked for about a year and a half on the processor, which was sent out for the first time in the Pacific Northwest a week ago.

Dan Ayres, coastal shellfish manager for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, called the instrument “a huge step forward.”

The state has a robust monitoring program on beaches, he said, but receiving data about offshore conditions would give people even more time to make decisions, such as when and where to sample shellfish for toxins or when and where to open beaches for razor clamming.

“If we had more time and can give businesses more time to plan, staff and place orders, and residents to make decisions, the impacts would certainly be lessened,” he said.

Last year’s toxic algae bloom roiled tourism in coastal communities and marine ecosystems and “hit us across the face,” he added.

Vera Trainer, who manages the marine biotoxin program at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center, said this year appears to be a much more typical year for toxic algae blooms.

The vision is to have multiple robots in multiple hotspots to track harmful algae blooms along the coast, she said.