By Mary F. Willson

For the Juneau Empire

Vertebrates have a broad spectrum of ways to care for their offspring. At one end of the spectrum are such species as herring and many other pelagic fishes that simply release their gametes into the water, where sperm meets egg, and the parents go off to do other things, providing no parental care at all. Avian brood parasites, which dump their eggs in other birds’ nests so the hosts rear the young, likewise provide no parental care (unless you count the effort of selecting the right nest to parasitize).

At the other end of the spectrum are species in which both male and female parents invest a lot of effort in caring for their young. For example, male and female of most species of penguin (except the emperor penguin male who does the incubating) and many other birds share the duties of both incubating the eggs and feeding the chicks. When the male does not incubate eggs, his care may be indirect: he usually feeds the female so she can stay on the egg-warming job longer. Among mammals, females of course nurse the offspring for a while, but in wolves and foxes, for instance, the male partners often bring food to the nursing mothers, and then both parents feed the young ones.

In between these extremes is an array of interesting arrangements, ranging from solo female care to solo male care:

—Solo female care: Many mammals leave all parental care to the females; males do no more than inject sperm to fertilize eggs. Porcupines, bears, and deer are local examples. A female salmon prepares a gravel bed for the eggs and she may guard her nest for a few days while the male she spawned with is off looking for other potential mates. Mallards and many other ducks also leave parental chores to the females.

Two species of very unusual frogs in Australian rainforest were not formally discovered by scientists until the 1970s but they were extinct before 1990. The females of these frogs brooded their eggs and tadpoles in their stomachs! Both eggs and tadpoles had ways of shutting down the digestive acids of the mother’s stomach while they were in residence. Geneticists and cell biologists are trying to resurrect a viable specimen of gastric-brooding frog from preserved tissue, but it would take more than one specimen before we could see this phenomenon in real time.

—Solo male care: This arrangement is known to occur regularly in certain birds, amphibians, and fishes. For example, jacanas are long-toed marsh birds that are customarily polyandrous; females are larger than males and defend territories that include the sub-territories of several males. The males do all the work of incubating and rearing chicks.

Spotted sandpipers have a variable mating system, sometimes monogamous but in some places they are polyandrous. A polyandrous female generally leaves her first male partner to do parental duties at his nest while she then pairs with another male, with whom she shares parental care.

The two species of Darwin’s frogs in Chile are called mouth-brooders, but actually the young are reared in the vocal sacs of the males, which ‘ingest’ the eggs and harbor them until they hatch. One of these frogs incubates the tadpoles until they can eat and then takes them to pools where he releases them to feed and grow up. The other species incubates both eggs and tadpoles; when the tadpoles become froglets, they just hop out of his mouth.

Fishes have been very inventive of ways for males to take over parental care. Stickleback males build nests and entice females to lay their eggs there, guarded by the males. Seahorse males incubate eggs in an abdominal pouch where the females inserted those eggs. The young ones emerge fully developed but extremely small. Intertidal sculpins often lay their eggs on the undersides of rocks, where they are guarded by males.

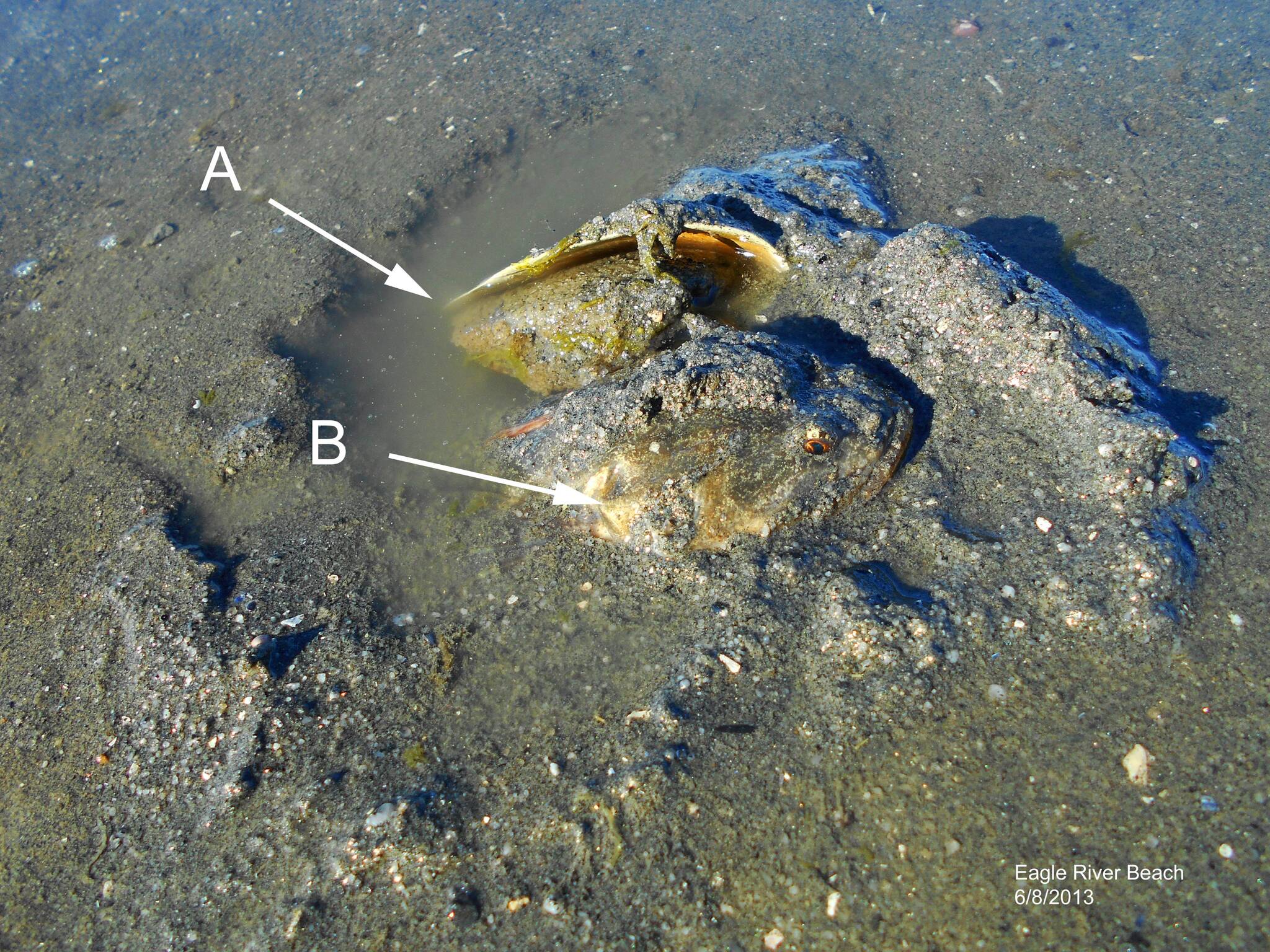

Ravens know another place to look, cuing two local naturalists to finding sculpin eggs under horse-clam shells worn like helmets on the heads of males buried in the sediments.

• Mary F. Willson is a retired professor of ecology.