By Vivian Faith Prescott

For the Capital City Weekly

With his orange gloved hands, my dad pops the shell off the crab, then twists the crab in half and pulls the guts off, and then puts the crab halves in the tote beside him. We’re processing Dungeness crab at Mickey’s Fishcamp. My dad tells me when his mother first came up to live in Wrangell, she worked as crab shaker at the local cannery. Crabbing and shaking run in our family.

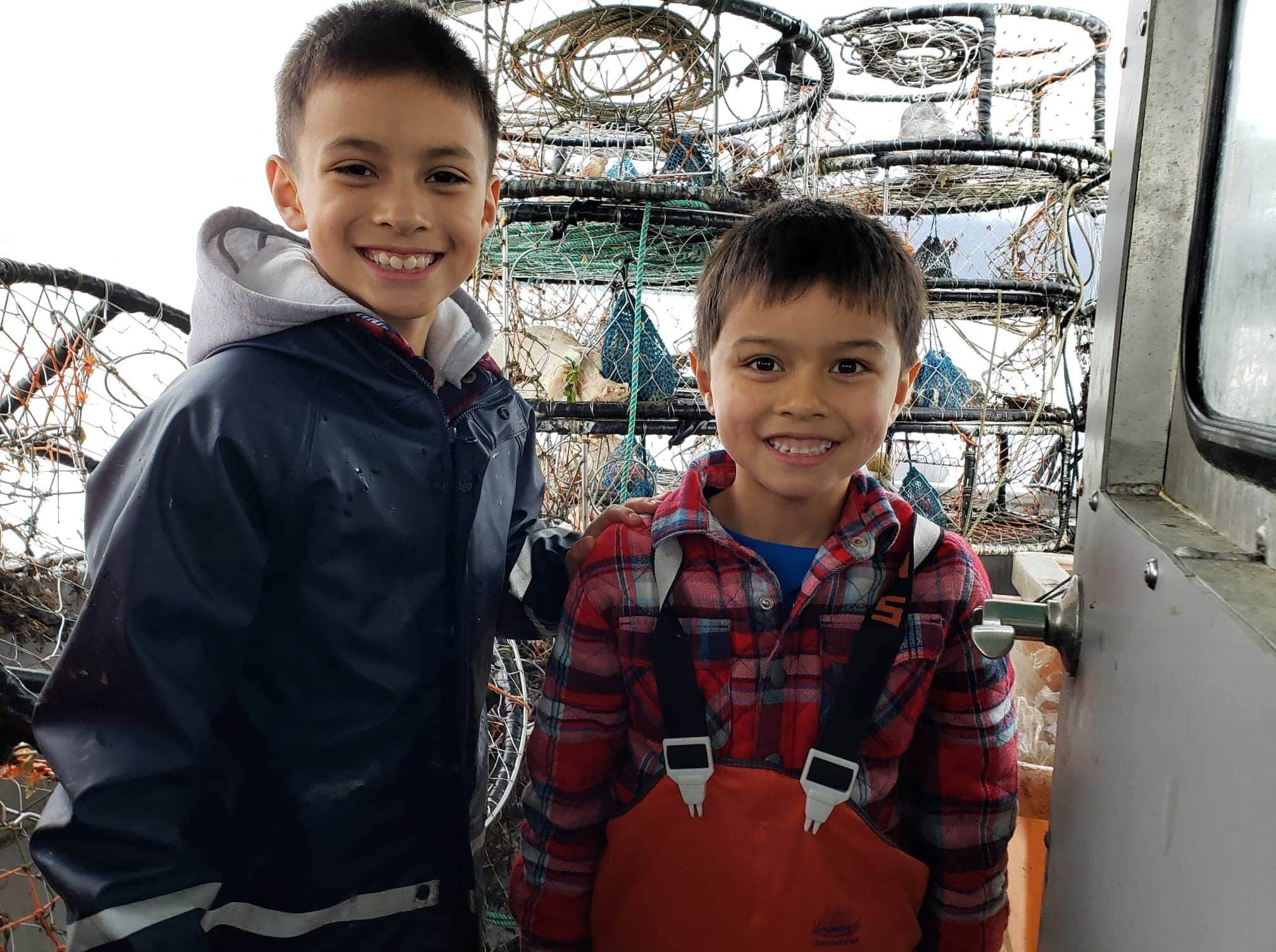

We bought these crabs from my son, Mitch Mork, who’s deck-handing for his dad this summer, along with my two grandsons, Owen, 9, and Chatham, 6. They’re working 225 pots around the Wrangell area. Mitch crabs partially for work but mostly to hang out with his dad. He’s also teaching my grandkids how to work hard and showing them that being an employee isn’t their only option in life.

Mitch is Tlingit and grew up commercial fishing in Wrangell and Sitka. He’s been a civil engineer in Anchorage for the past 12 years but now lives in Sitka.

“Now, I’m a domestic engineer, a homemaker,” Mitch said. “and a fisherman, a woodworker, landlord, photographer, stock trader and teacher.”

[Encounters with the giant Pacific octopus]

Mitch’s dad has been crabbing for decades, and he helped develop the local fishery. Mitch recalls crabbing on his family’s boat, the F/V Charmer, when he was young. He often worked for candy and remembers sorting through what seemed like endless soft crabs.

As I watch my own dad pull off crab shells, I think about all that goes into crabbing. Depending on permit size, crabbing takes the entire day. It’s easy enough to pull one pot, but the number of repetitions — at 150 to 300 plus — can wear on a body.

Every crabber has a different process but day-trip crabbers are on the water by 6 a.m. Crabbing requires lots of bait, mainly humpies or waste from the processors. They bait up bait bags, jars, and hooks on the way to the first string. They load up more bait before heading out or after the crab is delivered. Larger pieces of meat are cut up to fit in bags or put on hooks, and some are ground up for smaller bait jars. Every boat has its own technique, but basically it involves getting something stinky into the pot.

Mitch said, ideally, pots sit on the ocean floor for a day or two before you pull them. The crabbers head out to the first buoy in the string and the captain chooses an approach requiring the least effort, taking into account the direction of the current. The boat pulls alongside the buoy and they retrieve it either by hand or using a long pole with a hook. The slack in the line allows the line to be pulled up by hand to be placed in the sheave line hauler. The power is turned on and the rope is coiled onto the deck. Depending on the line length, it takes about 5-30 seconds to reach the boat and then the pot gets heaved onto the rail.

After the pot is aboard, the door bungee is opened, the old bait — if any — is removed. Crabs are then sorted to remove females, small and soft crabs, which are tossed back into the ocean. Crabs have to be males, identifiable by the narrow flap on the abdomen. Female flaps are wide. Crabs must be hard-shelled or they won’t have very much meat in them and the processor won’t buy them. The keepers are put into totes or large trash cans. As long as the weather is cool, the crabs stay alive all day. People can get sick from eating crabs that’ve been dead for too long before cooking them so they can only be sold alive. Larger boats that stay out for days at a time use tanks full of circulated or aerated water to keep the crabs alive. Most Wrangell boats are day-trip boats, though. After the crabs are sorted, new bait is added and the pot is reset again.

Mitch said even though crabbing is repetitious and at times monotonous there’s often something exciting going on. Sometimes there’s a pot bulging with a single huge octopus, loads of giant snails or even a halibut. Crabbers fight big waves, sea lions break open pots, and river sand holds pots tight on the bottom. Sometimes lines get stuck in the prop.

After picking a string of pots, the crab boat runs to the next set. Running time is often time to grab a snack, prep bait and clean the mess on the deck before it sticks. After all the pots are picked, it’s time to run to the processor. The boat is cleaned on the way to save cleaning time after the crab is sold.

A crab boat can wait in line in the harbor for 20-45 minutes before unloading. After they tie up to the processor’s dock, a bin is hoisted down into the boat. The crabbers dump smaller totes or cans into the bins and hoist the crab up to the processor. Large totes or storage areas on the boat that can’t be dumped must be emptied one by one. The deckhands must move fast because there are often boats waiting. Mitch explained they can’t take their time selecting a safe place to grab a crab either, so being quick usually avoids being caught by an angry claw. After unloading, the paperwork is signed and the crabbers head back to the dock to ready the boat.

One of the difficult things about crabbing is that pots can get lost and then they are ghost fishing. Ghost fishing is when pots keep on fishing without bait or fishermen to pick them. This is a worldwide problem. If the crabs or other life can’t get out, they die. To combat this problem, there are rot string regulations. Every season, the rot string (cotton twine), is replaced. The doors on the pots are fastened with this twine that falls apart in a short period. This prevents long term ghost fishing and allows the crabs to push their way out.

Crabbers can lose pots for a variety of reasons, though, and it digs into profits. Wrangell has a lot of logs in the water from the Stikine River that catch buoys and drag pots into deep water. Pots can also be sanded down so much they can’t be retrieved. During crab season, Wrangell’s shoreline is dotted with colorful buoys. Pots are so close to one another that lines can be cut by props. Inexperienced crabbers can even set pots too deep for their line. Pots can disappear in big currents only be seen again at low tide. And worst of all, pots can be taken by thieves, which is sometimes a problem in Wrangell.

[Planet Alaska: Carrying on our traditions]

Now, as I sit outdoors beside my dad watching the crab-cooker boil, I consider how our family is connected to crab, from pulling pots, to processing and eating. It’s reassuring knowing that with my grandsons, Owen and Chatham, a new generation is learning to crab.

Tomorrow will be a long day picking crab meat. But tonight, when I fall asleep, I’ll be thinking about what I want to make from the crab: crab patties, crab mac salad, cream crab on toast, crab crepes, crab casserole, crab dipped in butter…

• Wrangell writer and artist Vivian Faith Prescott writes “Planet Alaska: Sharing our Stories” with her daughter, Vivian Mork Yéilk’. It appears twice per month in the Capital City Weekly.