A few weeks ago I awoke to cooing doves, a warm Hawaii breeze, and the scent of Kona coffee tugging at my soul. I have Hawaiian heritage, so something magic happens when I’m walking on Hawaiian soil, surrounded by sun, water and sipping Kona coffee. Maybe it was my coffee that fueled my artistic side that day. But I came up with a New Year’s challenge to draw an ovoid a day.

I don’t have a competitive spirit. I cheer for both teams at sporting events, plus I’m not someone who takes on New Year challenges. I am the kind of person, though, who likes to challenge myself.

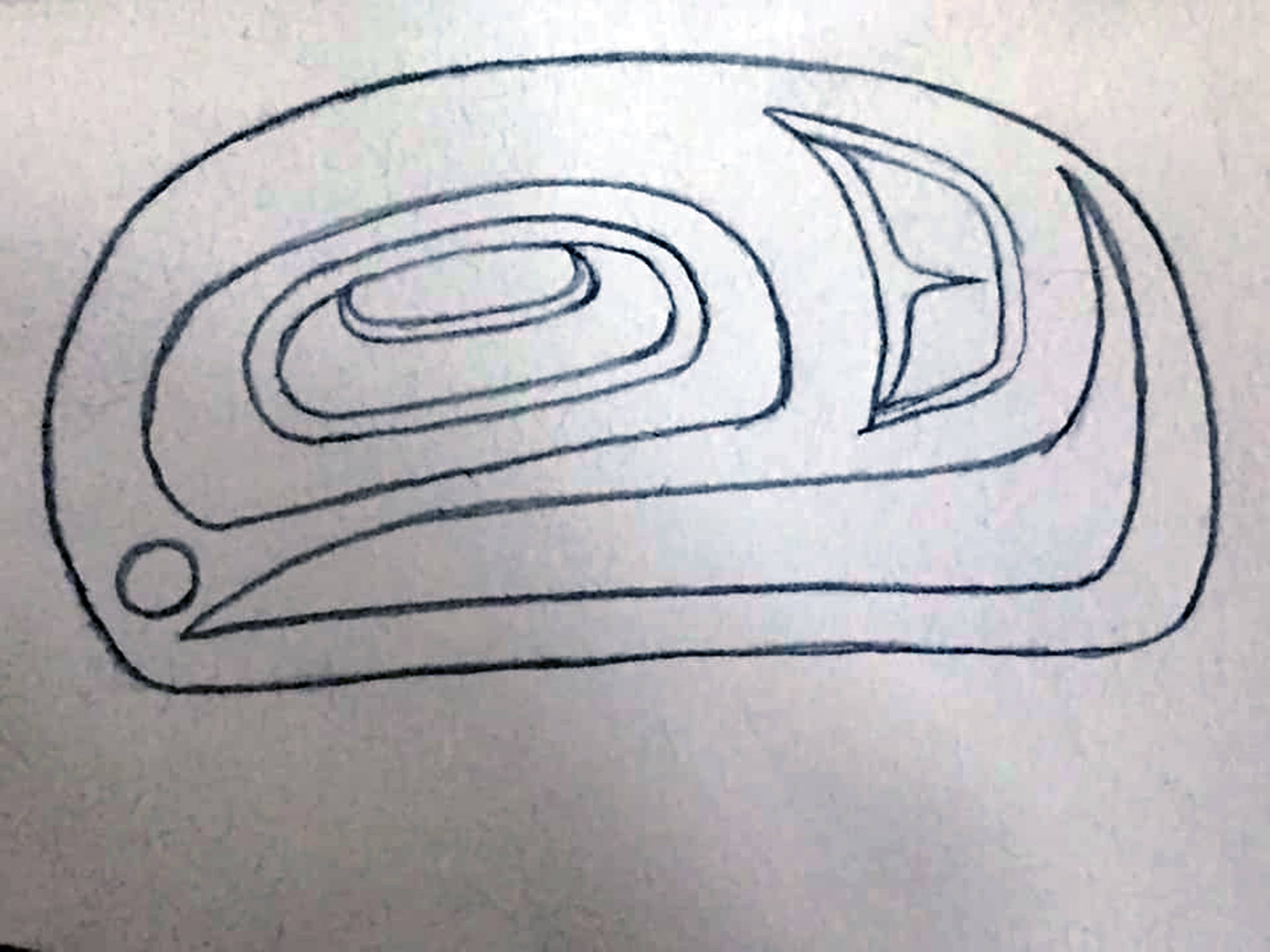

Wait, what’s an ovoid you ask? If you’ve seen Northwest Coast art, you’ve seen it. An ovoid is similar to an oval. It’s somewhat egg-shaped and in Northwest Coast art ovoids have a flatter bottom line. Ovoids often represent human or animal body parts: wings, fins, eyes, shoulders, hips and hands. Among Northwest Coast artists, an ovoid is sometimes called the mother of designs, meaning it’s the central artistic element from which all other design elements flow.

The first step to learning any art is to start. The next step is practice. Through practice we make mistakes that teach us, and we continue to practice. In Northwest Coast art, apprenticeships are all about practice. I’ve worked on my Northwest Coast Native art (also called formline art) techniques for decades. As a Tlingit, I feel obligated to ensure the art form continues. I remember when not many people were practicing this art form. Over the generations, colonization efforts had convinced people our art was evil and not something “civilized” people did. Our people also suffered from transgenerational trauma, so picking up an adze or even a pencil to paper, or threading a bead to sew a design on a dance robe, was often painful.

Fortunately, as a child in the early 1980s in Wrangell, I happened to encounter a couple of Master Carvers working on replica totem poles for our Chief Shakes House. It was a warm summer day, near the area of the old Russian fort beside Shakes island, what was then and still is a potholed muddy parking lot. I’d gone to work with my dad who was the Harbormaster at the time. His office was nearby. We stopped to see how the carvers were progressing. I followed my dad to where the men were busy carving. We stood watching when Steve Brown, the carver closest to us, looked up at me and asked if I’d like to try it. I was a shy 5-year-old and I shook my head no. My dad said go ahead and try it and nudged me toward the carver. I held the adze with my small hands and Steve wrapped his hands around mine and with both our hands clutching the adze I began chopping into the wood. I recall a kindness in his eyes as he gifted me this moment from my ancestors. It was the beginning of a very long journey.

I grew up with the knowledge that women were not normally carvers in the Tlingit culture, but a couple decades later, in the early 2000s, I was the only woman in almost every single Northwest Coast art class I took. Fortunately, things have changed since then. It’s wonderful to see so many female Northwest Coast artists. A few of my favorite female Northwest coast artists are Heather Bell Callaghan, Lianna Spence, Allison Bremner Marks and Crystal Worl. I highly recommend taking a look at the art these women do. They’re amazing!

You don’t have to be a natural at it to practice formline art. When it comes to this art form, I’m not very good. I’m OK. It takes me a really, really long time to draw or carve anything. Though I’m not confident in creating my own designs, I still try. Mostly, I’ve never put in the kind of effort it takes to become really good. I’m a dabbler. This art takes lots of practice. I work on formline art because I love it. It’s an extension of my soul. It connects me to my ancestors. Northwest Coast art pre-dates the Roman Empire, the Egyptian pyramids and the Greek Parthenon. Formline art is one of the world’s oldest art forms, yet the world almost lost this art due to the path of colonization. There are many people, in the past and present, who’ve worked hard to make sure our formline art not only survives but thrives.

I’ve had numerous formline art teachers, but one of my all-time favorite teachers was one just this last year when I had the opportunity to take a class through Sealaska Heritage Institute from David Boxley Jr., a Tsimshian artist. He and I attended college together at UAS in Juneau years ago. Boxley uses humor to break down students’ inhibitions about learning art and he explains the techniques in a unique way. He’s patient and provides what you need as an artist at whatever stage you’re at.

In Boxley’s class I experienced the ah hah! moment I needed to continue my journey as an artist. He was great at explaining everything. He also reminded us that the ovoid is the heart of the art and we could perfect the ovoid by drawing them over and over. This practice creates muscle memory. Tlingit art isn’t always drawn freehand. Before tracing paper was invented we used ovoid templates made from tree bark, or from wood left over from carving projects. Boxley taught us to use tracing paper and templates when we needed and to look to the old masters and learn from them. You can access David Boxley’s class on Sealaska Heritage Institute’s YouTube channel.

Today, I do some formline art freehand, but not always. I need practice! That’s why I’m doing an ovoid-a-day challenge. If I draw one every day for a year, my hand will create muscle memory and it’ll be easier and easier to draw ovoids. Here’s a tip: In order to create symmetrical ovoids a common practice is to draw one half of the ovoid and then trace it to the other side to make it even. Especially if the same size ovoid is being used throughout a complicated piece.

No matter if I’m in Alaska or Hawaii being outdoors inspires me. While on vacation in Hawaii I drew ovoids by the light of a camping lantern at Spencer Beach on the north end of the Big Island. As I listened to the whales that’d migrated from Alaska, I drew ovoid after ovoid. There were moments when I wanted to do other things, but I always carved out time to draw an ovoid. I drew ovoids in Hilo, Kawaihae, Kona and Captain Cook.

After taking on this challenge I’ve found myself experimenting with my own designs. I am on my own path. Yes, I am only challenging myself, but if you’d like to join me, just start. Draw an ovoid every day and little by little we’ll perpetuate the ancient art form into the future. Come along with me as if we’re in a canoe paddling the shoreline observing the positive and negative space, the crescent and circle, the trigon, the “s” shape, the split-u and the ovoid. Formline art is our coastline, our rivers and inlets, the shape of the hills rising from behind our homes, how the clouds roll and creep across the forest, the way brown bear’s hump arches above its back, and the ovoid eye looking back at us from the knots on the alder’s bark. The ovoid is the heart of it all.

• Vivian Mork Yéilk’ writes the Planet Alaska column with her mother, Vivian Faith Prescott. Planet Alaska publishes every other week in the Capital City Weekly.