By Vivian Faith Prescott

For the Capital City Weekly

Dolls are universal.

“I haven’t come across a culture, a country, a continent, or a people, who do not have dolls,” said artist Kristina Cranston. As I peered into her doll world, I noted a tiny yellow-beaded octopus bag slung on the shoulder of a doll with moccasined feet. Miniature clay cups sat atop a small dresser as if ready for tea-time and a little button blanket hung on the wall.

Cranston is a multidisciplinary artist — carver, writer and dollmaker — born in Haines, Alaska, who now lives in Sitka. Her father is Tlingit, and her mother was non-Native so she was adopted by the Shangukeidí, Thunderbird, a clan of the Eagle moiety in Klukwan.

“I grew up with my mother and younger sister in the Anchorage area and spent summers in Southeast visiting my father, berry picking, helping at fish camp and having fun with family,” Cranston said.” Both my parents have Southeast Alaskan roots. My great grandparents on my mother’s side started homesteading around 1938.”

Her first memories are creating paper dolls and clothes with her mother when she was just two years old. For doll-making supplies, they used readily available materials from their home. They made stick dolls, cloth dolls, stuffed dolls, clay dolls, cornhusk dolls, and more.

[Singer-songwriter from Juneau gets a golden opportunity]

“My mother was handy and resourceful,” Cranston said. “Being a poor kid didn’t mean we didn’t have dolls. If we couldn’t buy it, we made it. I’ve continued that tradition. Many of my children’s toys — Waldorf dolls, wooden dolls, doll houses, stuffed animals and felted critters — were hand-made by me, or they made their own toys.”

Doll-making isn’t her only art, though.

For seven years, Cranston apprenticed with her husband, Tommy Joseph, a master carver. She lived and breathed carving. “I treated it as a job,” she said. “It connected me to a very rich world.”

Unfortunately, Cranston suffered an injury and is not able to carve wood anymore.

“Between apprenticing with Tommy, my hand injuries, and working with miniatures, I learned patience,” she said. “That’s huge because I’m not known for patience.”

Her renewed interest in doll-making is an outgrowth of her apprenticeship and dedication to carving over 40 portrait masks.

“It was all about masks, finding that face to tell its story,” Cranston said. “The dolls I make are similar: old faces, young faces, a diversity of faces. Old faces are my favorite. I’m obsessed with faces in general.”

She is inspired by both imagined and real people. She begins creating dolls with a general prototype but she doesn’t force a face or story. Every doll in unique but she stressed it’s also important to have technical consistency.

When researching doll-making, Cranston discovered how talented and resourceful Indigenous dollmakers are.

She said her work is like “Play-Doh” compared to theirs and she’s inspired by the quality and variety of dolls.

In fact, Cranston’s great-grandmother, Minnie Johnson from Yakutat, was a dollmaker.

“I’ve only seen a photo online in the Alaska State Museum archives,” Cranston said. “She was a seal hunter and skin sewer. She also raised many children who weren’t her biological children, but they were still her children, so it makes sense that making dolls was a natural thing for her to do.” As well, her great-grandmother would’ve used materials she had access to. “We are resourceful people. She hunted, processed her foods, and made whatever she needed and wanted.”

Creating mixed-media dolls and puppet-making are Cranston’s favorite, and she especially loves making her Grandmother and Grandfather dolls. She incorporates sewing, clay, wood, wire armature, wool, hides, fish skin into the art.

“I imagine what a small child feels when they hold one,” Cranston said. “They even jingle a bit. My grandchildren love them. Adults seem to love them. They just feel good to hold.”

She often constructs intricate and elaborate dioramas to tell contemporary life stories with the dolls as central characters. The dioramas are an artform in themselves. Dioramas, three-dimensional scenes, are commonly found in museums and galleries as well as model hobbyists’ garages, but Cranston’s home holds space for hers.

“The diorama reveals itself. The dolls tell a story and I set the scene.” Cranston said.

She explains that looking at a diorama is like peeking into a window. Diorama means “through that which is seen, a sight.”

The diorama is a place to pause, to take in, to notice, to examine. You spend time with it.

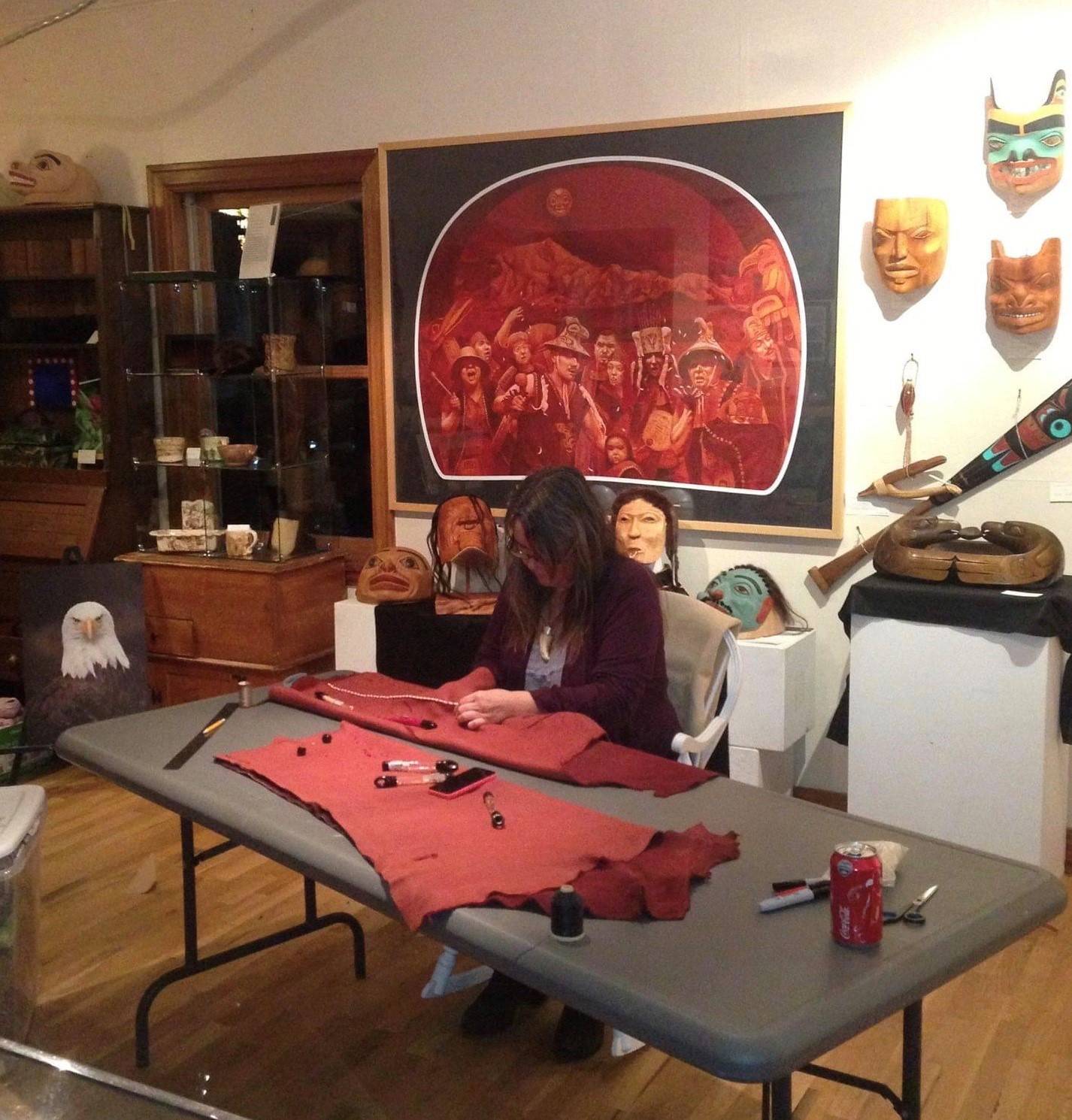

Found objects create the dioramas and if Cranston doesn’t have an item, she makes it. She might incorporate other people’s work into her dioramas just like in real life. She lives in a home studio and gallery so they live and make art among other artist’s work as well as their own.

“Our home-studio has a lot of old pieces, materials, so in a sense, working with what’s around you is like pulling cedar bark from the same tree our ancestors pulled from,” Cranston said.

As Cranston described: “When I’m setting up a scene, I can smell the woodstove, or hear an old man’s laugh, or imagine the feeling in the room. I hear drumming, adzing, or a creaking chair. Mostly because it’s familiar objects. There’s the smell of coffee and cedar and burning wood, all ways of living and knowing come through exploring the diorama.”

Her scenes are contemporary but there’s a look that reminds the viewer of the past. “I use spooled cotton thread, but I use sinew as well. I use cotton hand-sewn fabric, hides and fur. Mostly all natural fibers and materials.” Like Tlingit dollmakers before her, Cranston enjoys repurposing and incorporating found objects. Her children also contribute to the dioramas, especially her two youngest.

“They may make a piece of furniture or sew a miniature button robe,” she said.

As an artist and partner to a renowned master carver, Cranston deals with a lot of business and technical aspects of the art world. She explained that it’s hard to switch gears from grant-writing or letter-writing to the actual art-making, but also when she must decompress from life’s stressors, she creates art. She typically sets aside several days in a row to her doll-making and dioramas.

[Anacoma Slwooko’s dolls featured at local doll museum]

“I make accessories, the hand-works stuff: needle felting, sewing, molding, whatever I need,” she said. “And then I play. I set them up. I take photos, and I listen and get to know them. This is a peaceful process. Like play therapy. I create peaceful places that create calm emotions, curiosity, and joy.”

One of her goals is to have her dioramas featured in a museum or gallery where the public can enjoy them. This idea could also be translated into an online diorama as we live with COVID-19. She wants to share her dolls and dioramas with the world and hopefully revitalize the doll-making art.

For Cranston, art is political and social. Art is everything.

“But too many things we collect as art cannot be touched,” Cranston said. “Things are hung on a wall, put behind glass, or on a shelf out of reach. These dolls have texture, weight, smell, softness, and some have wire armatures to manipulate and some have strings: they all require play time. I try and make them with that in mind. Who am I ultimately making these dolls for? Could a three-year-old child enjoy it and it could be put on a shelf or behind plexiglass? I sure hope so.”

Doll-making is a slow, deliberate art process. Between her time apprenticing with Joseph and learning the challenging medium of woodcarving, and her hand injury, Cranston learned to slow down. She’s learned not to take shortcuts, to enjoy the process, and, importantly, to set the time and space to be able to create and play.

“Doll-making connects me to community and has enriched my experience as a Tlingit woman,” Cranston said. “It’s connected me to my culture, traditions and skills.”

Like Cranston, I discovered you don’t have to be a child, or a dollmaker to find joy in miniatures, you simply have to peer into that world — Oh, look, there’s an elder holding a small skin drum. A miniature drumstick is raised in the elder’s hand as if ready to pound the drum. I can almost hear the song.

• Wrangell writer and artist Vivian Faith Prescott writes “Planet Alaska: Sharing our Stories” with her daughter, Vivian Mork Yéilk’. It appears twice per month in the Capital City Weekly.