My dad would sit at the kitchen table with a small block of cedar in front of him, slicing off thin pencil-like pieces. He was making cedar pegs, a long-lost salmon fishing tool. The cedar peg shapes the herring, curving it to mimic a wounded herring flashing silver. My dad claims that salmon like the scent of cedar. He’s caught a lot of salmon in his lifetime, so I believe him.

There’s an art to knowing salmon and your fishing gear. My dad caught two big king salmon yesterday, so today, we’re sitting in front of the smokehouse on lawn chairs watching the alder smoke curl up from the vents and passing time by telling stories.

The Sámi way of storytelling is telling many stories at once, one story leading to another and another. My dad caught his first big king salmon when he was 9 years old. In his own words:

“Dad and I were out trolling in Sunny Bay in the morning. My dad had a 9 foot Davis built skiff, a wooden rowboat with no motor. I was rowing it along the beach, hand trolling with a blueberry branch and line. I used a blueback wooden plug for bait. I trolled along the shore and Boom! The fish started pulling me around out toward the straits. I let him fight until he got tired and when the skiff stopped moving I pulled the line in. After I let him fight the skiff he didn’t have much life in him. I couldn’t pull him in because I was too little and he was too big, so I tied him up to a little cleat on the back of the skiff. I had enough sense to know you have to tire a big salmon out or it’ll wear you out. I rowed back over to my dad’s big boat and he helped me land it. It was a big 50-pound king salmon!”

Ripples of knowledge and water

My dad learned to fish salmon from his dad, my grandfather, who learned many of his fishing techniques from the Tlingit and Scandinavian fishermen he knew.

[Planet Alaska: Carrying on traditions]

My dad is 80 years old now and life is filled with salmon memories. The stories and lessons are as varied as fish jumps, but they all teach me to be a better salmon fisherman. There’s an art to the bend in the herring, to knowing which fish jumps in front of the fishcamp.

My dad explains:

“You can tell by the jumps if the fish is a king salmon. Kings jump all the way out with a big splash, usually one to three jumps at a time. Cohos jump clear out of the water, too, but don’t jump as many times, usually a single jump or two. The sockeye part-way slides on their side, and their tails stay in the water. The sockeye are easy to spot like skipping a rock—skippin’ rock sockeyes. You can tell because they jump three or four times in a circle. The humpy flips. He jumps a single jump with a smaller splash. In a big school the humpies jump all over the place. And the dog salmon, they jump but not as much. They come to the surface and do a lot of finning. You watch for finners besides the jump. Diving dogs we call them. They go down under a sein to avoid the net.”

From fishing salmon around the islands his whole life my dad can also tell where the salmon are from, where they’re headed:

“A hatchery fish will stay down and fight like a cross between a halibut and a salmon. A Stikine River king comes up to the surface fast and the salmon are long and narrow. Bradfield kings are short and stocky and bigger than the Stikine king salmon. They fight a lot. Aaron’s Creek kings have an emerald green back instead of bluish. There’s no mistaking them. Ocean run kings are heavily bright like a herring and are good fighters. They’re always red. I’ve never gotten a white one out there. Usually, winter kings are more white kings because there’s less krill to feed on.”

Time-proven technique

I marvel at this knowledge and wonder if I’ll remember everything. My dad gets up from his chair and checks the smokehouse fire. He adds another alder log and it starts smoking good.

He sits back down and I ask him about choking a herring, a term I’ve heard my whole life. My dad says choking a herring is a troller term used in the old days.

He learned this technique from his dad, my grandfather: “People don’t know how do that anymore. The hook is different than a normal hook; it has a flat shank rather than round. When I was about nine years old I’d sit on the boat during the bad days and make the cedar pegs for him. You use the pegs when you choke a herring.”

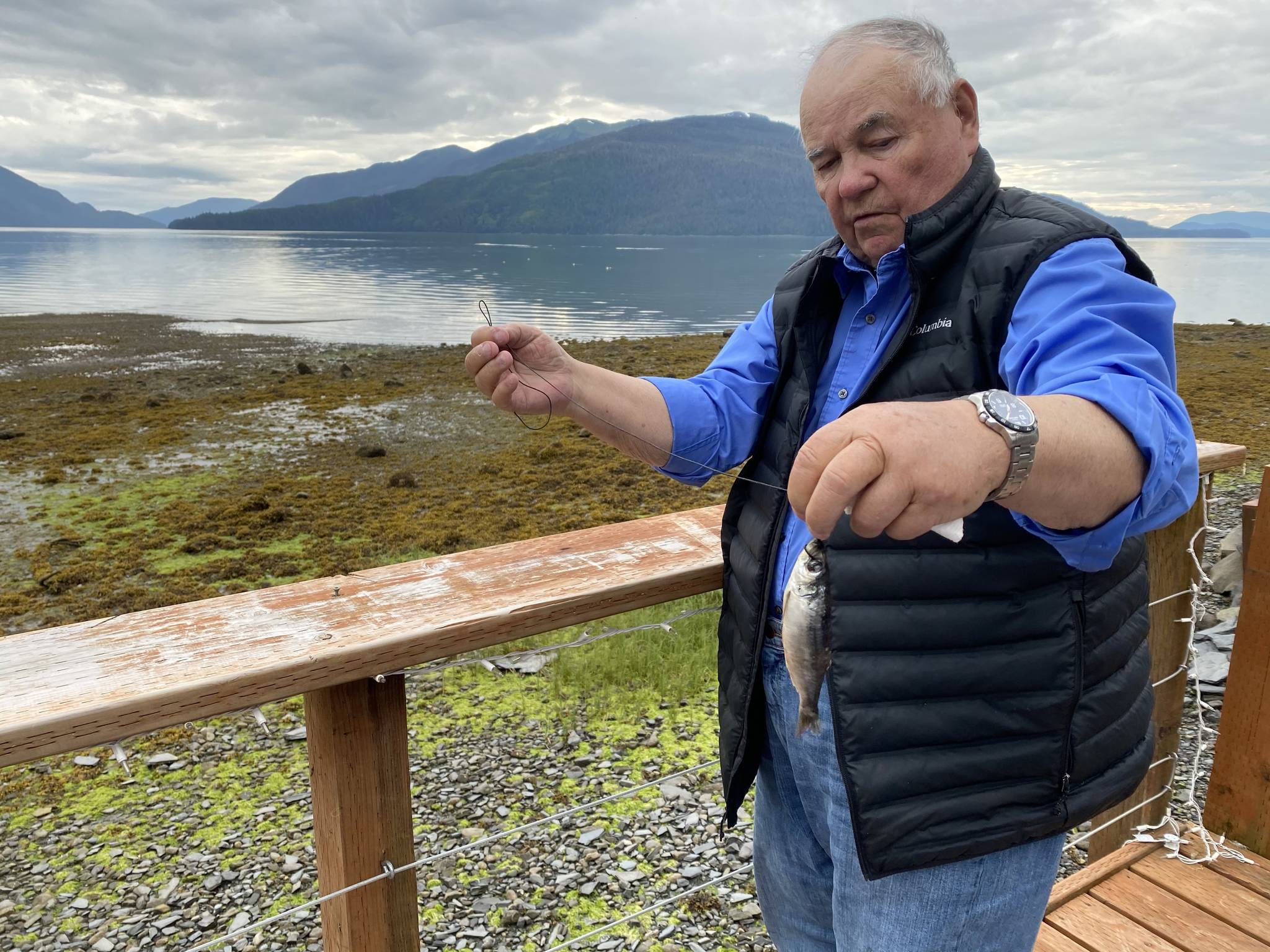

He shows me using his hands as muscle memory, his fingers forming a hook and an imaginary line.

“With the hook and line you come up through the gill-flap and come out by the eye, and then down around the head, jaw, and gill-flap area. Then with the hook you go through the opposite eye and come out through the other eye. It makes a stitch around the head and mouth. Then insert the hook into the body right behind the gill-flap and bend the herring. You feed the hook as far as you can toward the tail. Then you bring the back of the hook out of the body into the curve. If you have slack, tighten the slack. Insert the herring peg through the opposite eye following the backbone until it almost pokes out.”

He makes a snapping motion with both hands. “Then break off the end of the herring peg. Cedar breaks when the fish strikes.”

I get up to check on the salmon in the smokehouse. I open the door and smoke pours out. I look over the racks. “Looks good,” I say. “About another hour.” I go back to my chair and sit down. We are quiet for a few minutes, comfortable in the silence.

“What about Lil’ Joes,” I finally ask. A few years ago he made me a trolling plug.

“I taught myself how to make Lil’ Joes,” he says. “That’s what the manufacturer called them but they’re plastic. It’s a commercial trolling plug. Those things are hot right under the surface. The big Bradfield kings went nuts for them. Only down two fathoms. I couldn’t find any more plastic ones and there was no internet then, and no one locally carried them, so I decided I could make them for nothing. So I carved the Lil’ Joes from red cedar and painted them.”

A life teeming with stories

As the smoke wafts up through the hemlock branches and the spruce trees, we laugh at the crows who’ve discovered we’re smoking fish today. We talk over them.

My dad gets up and goes into the nearby shed and brings out a brightly colored gaff in his hands. He hands me the gaff. “I took an old gaff hook and dressed it up a bit.”

[Planet Alaska: Encounters with the giant Pacific octopus]

As he shows me his new/old gaff hook where he wrapped line around it then put some new-fangled rubber paint on it, he starts to tell a story.

“My old gaff was pretty good. I had it for years. I was pulling up cohos like a bugger and I went to bonk the fish but the distance was too short and I stuck that hook between my eyes. Talk about a headache. All those years I’d been gaffing fish. I looked like someone shot me with a .22 between the eyes.”

“Jeeze, I say,” laughing, holding the sharp gaff. “It’s a wonder you survived.”

Now, I’ll remember not to bonk myself.

I’m sure glad my dad made it this far through a life teeming with stories and a full smokehouse so he could teach me the art of salmon.