It’s far from a whale of controversy, but a statue proposed for a plaza in front of the Alaska Capitol is causing some discomfort by literally putting a 19th century imperialist on a pedestal.

Last week, KTOO-TV in conjunction with the Alaska Historical Society hosted a panel of historians to discuss a statue of William Henry Seward and the legacy of the Secretary of State who negotiated and executed the Alaska Purchase.

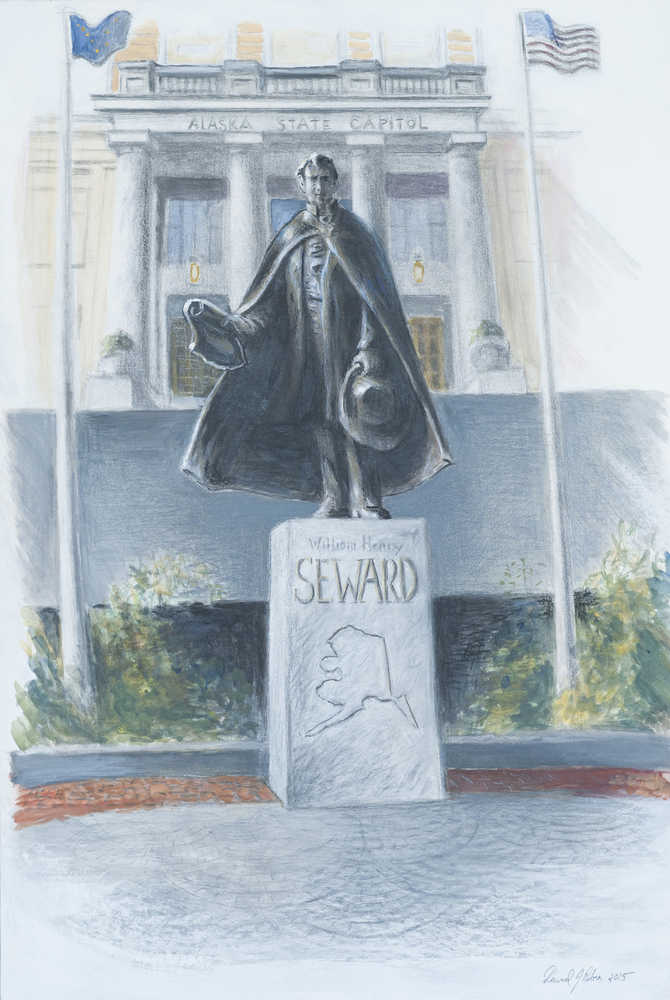

For several years, Juneau residents have been working to erect a statue of Seward in front of the Alaska Capitol to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the purchase, but not everyone is pleased.

Ross Coen, editor of the journal Alaska History, said the bronze image of Seward “represents a heroic past,” but “we should recognize, however, that not every Alaskan feels the same way about that history. Not every Alaskan will see himself or herself … in the statue.”

Jon Ross, former director of the Alaska Native Heritage Center, agreed. He said it’s important to remember that the Alaska Purchase was a deal between nations and took little note of the people who were already living there and had their own ideas.

In his 1869 visit to Sitka, Seward declared that the Native nations of Alaska “are jealous, ambitious and violent,” then went on to predict that white workers would soon arrive in the territory to develop its resources.

“The Indian tribes will do here as they seem to have done in Washington Territory and British Columbia: they will merely serve the turn until civilized white men come,” Seward declared.

Wayne Jensen is co-chairman of the committee in charge of erecting the statue by next summer.

He participated in last week’s forum and said that to examine Seward’s comments alone is to strip them of their context.

“The statue just provides an opportunity to learn about that event (the Alaska Purchase) in history,” he said.

Seward’s action was the start of something great, what historian Terrence Cole called the advance of liberal democracy. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act might not have been enacted until 102 years after Seward’s visit, but it did arrive.

“There’s been progress — significant progress,” said historian Stephen Haycox. “American culture is not what it was, nor is Alaska. Alaska Natives are accepted and integrated into Alaska’s political and social fabric as never before.”

The statue was inspired by John Venables, the acclaimed historical re-enactor who traveled Alaska in the guise of historic figures like Judge James Wickersham and Seward.

He was an advocate for the statue and in 2013 held a ceremonial groundbreaking for it while dressed as Seward.

“This will be a great photo op for a million cruise passengers coming to Alaska and other guests and our visitors and residents,” he said at the time.

He died in 2015, a few months after Ketchikan artist David Rubin began working on the statue.

Jensen said there’s been no shortage of support for the statue, whose $120,000 estimated cost has been paid by private donations and by the City and Borough of Juneau, which provided about a fifth of the cost in a 2015 Assembly appropriation.

“I think a lot of people support it, otherwise we wouldn’t have gotten the money for it,” Jensen said.

Rosita Worl, director of Sealaska Heritage Institute, did not attend last week’s forum and offered her thoughts by email.

“We can understand that some Alaskans want to acknowledge and honor Seward for advancing the sale of Alaska to the United States with a statue,” she wrote. “I am not adverse to the Seward statue, but I would hope that the public would also understand that Alaska Natives have differing opinions and mixed feelings, and would also like our story to be acknowledged.”

She went on to say that ANCSA resolved some land issues, but it didn’t “include the adverse impact that came with the oppression of Native culture and languages” or the horrific work of boarding schools.

Jensen said there are plans to acknowledge that story. Accompanying the statue will be two interpretive panels with 500 words apiece to put the statue into context. It isn’t easy to distill history into 1,000 words, but that work is ongoing, and Jensen said he hopes the panels will encourage people to learn more.

There’s also one tangible note on the statue itself.

During the design process, statue backers debated whether they wanted to depict Seward as he was when he helped Lincoln defeat slavery in the United States, or if he should be depicted as he was when he visited Alaska.

On the night Lincoln was assassinated, a deranged pro-Southern attacker attempted to kill Seward as well. The attack left the Secretary of State alive but wounded, and he was scarred for the rest of his life.

If the statue represents a “heroic” version of the past, as Coen has argued, it’s a past with scars.

“We can learn from the past. In fact, it can be argued that’s what it’s for,” Haycox said. “I believe it’s entirely appropriate for Juneau to commission a statue of William Seward, but I would preserve the scar.”

The Seward panel discussion is online at www.youtube.com/watch?v=UIeofN6LX04 and will air on broadcast TV via 360North at 8 p.m. Friday.