Suspended in netting in a downtown Anchorage building is a potent symbol of Arctic climate change: a chunk of sea ice that started at 310 pounds but is steadily shrinking, that was transported from Utqiagvik to the Dena’ina Civic and Convention Center.

The ice was set up as a prominent display at the Arctic Encounter Symposium, which runs through Friday. At the event, which has attracted an international crowd of about 1,000 scientists, policymakers, business leaders, Indigenous leaders and other interested parties, the role of sea ice has been a prominent theme.

Arctic sea ice is fundamental to marine ecosystems, cultures and the practical needs of people living in the region, they said.

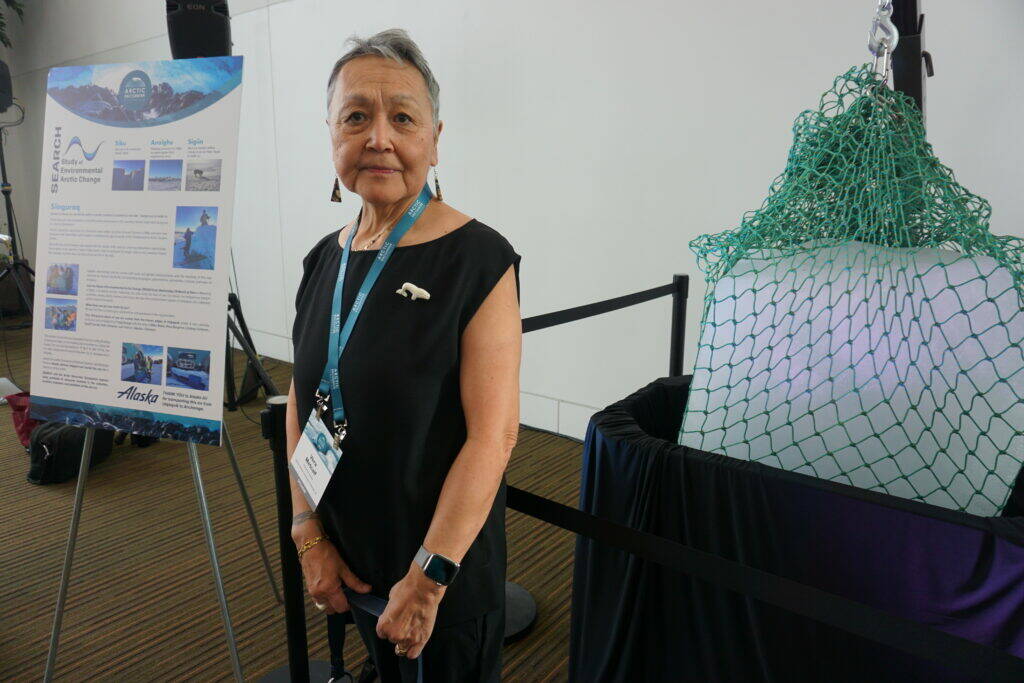

Known broadly to Indigenous people as “siku,” it is so important that there are numerous names for the widely varying sea-ice conditions, said Vera Kingeekuk Metcalf, executive director of the Alaska Eskimo Walrus Commission and a veteran of other Arctic organizations.

Drops of meltwater form on Thursday at the bottom of a chunk of sea ice set up as a display at the Arctic Encounter Symposium in Anchorage. The ice was transported from Utqiagvik and originally weighed 310 pounds. (Photo by Yereth Rosen/Alaska Beacon)

Drops of meltwater form on Thursday at the bottom of a chunk of sea ice set up as a display at the Arctic Encounter Symposium in Anchorage. The ice was transported from Utqiagvik and originally weighed 310 pounds. (Photo by Yereth Rosen/Alaska Beacon)

In a panel discussion on Wednesday, she went through several of the words used in the Siberian Yupik language of her homeland, St. Lawrence Island at the southern edge of the Bering Strait.

There is “miluta,” or new fall ice, a word that doubles up to describe throwing; and “saqralqaq,” meaning ice that is solid enough for walking but soft enough that walkers leave footprints that fill with water, she said.

There is “kulusiq,” meaning iceberg, something becoming less common, and a word of warning that’s becoming more commonly used: “pequ,” which describes “an unsuitable area in ice field where the current causes ice to heave up or break up,” she said.

“I share these words not simply to show that we have many descriptions of siku. I just hope to explain how critical it is for those of us, our Indigenous people here in the Arctic, because we have a really clear and intimate knowledge of what siku means,” she said.

Cyrus Harris, a natural resource advocate for the Kotzebue-based nonprofit Maniilaq Association, described the practical impacts of ice loss. “For me, sea ice melt is a hazardous thing for travel,” he said in Wednesday’s session.

Ice now forms up much later in the year than it used to, and when it does form, it is thinner and subject to freeze-thaw cycles, Harris said. Loss of ice also means less material for building structures, he said. “We depend on that thick, what we use to call ‘polar’ ice, which we don’t have anymore,” he said.

Aside from impacts to food security, wellness and other aspects of life, loss of sea ice is expensive, said Jackie Qataliña Schaeffer, director of climate initiatives at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium.

“All that sea ice was natural, free infrastructure from nature to protect our shorelines, protect our infrastructure that was built, protect our communities. And that is gone,” Schaeffer said, citing repeated floods and erosion problems. “Economically, every community along our coast is threatened by fall storms because we no longer have that free infrastructure.”

But there are economic upsides of sea-ice loss, said Larry Pederson, a vice president for the Nome-based Bering Straits Native Corp.

He listed as opportunities the increased ship traffic, including shipments of cargo, energy sources like liquefied natural gas and cruise ships carrying tourists to Nome and other parts of the Bering Strait region. For local fishermen and those who hunt by boat, the longer open-water season also presents opportunities, he said.

The pending development of a deepwater Arctic-serving port in Nome is an example of a potential economic boon, he said. Aside from bringing jobs and revenues, port development could enhance regional safety, he said, pointing to the traffic of Russian tankers already ferrying liquefied natural gas through the Bering Strait. “If the Russians are coming through already, what’s to say one of their LNG tankers doesn’t run aground at some point?” he said. That could mean a response from Nome within hours, rather than a response from the full-service ports in Unalaska or Kodiak that would take days, he said.

The rising sun lights the sky over frozen Norton Sound in Nome on the morning of the 2018 winter solistice. Sea ice formed late that year; winter ice extent in the Bering Sea hit record lows in 2018 and 2019. (Photo by Yereth Rosen/Alaska Beacon)

The rising sun lights the sky over frozen Norton Sound in Nome on the morning of the 2018 winter solstice. Sea ice formed late that year; winter ice extent in the Bering Sea hit record lows in 2018 and 2019. (Photo by Yereth Rosen/Alaska Beacon)

Those economic opportunities come with risks, such as increased dangers of accidents among the larger number of ships heading in and out of the Bering Strait, he acknowledged.

Summer sea ice extent has declined at a rate of 12.4% per decade as a result of human-caused climate change, according to NASA. The declines affect other seasons, too; the winter maximum reached on March 6 was the fifth-lowest in the satellite record, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. And what ice exists is thinner and younger than it was decades ago, according to the NSIDC.

John Holdren, who served as science adviser to President Obama and is now with Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, said it is important to understand that loss of sea ice has impacts far beyond the Arctic. It has affected atmospheric and weather patterns, skewing atmospheric rivers that are “creating enormous havoc across the world,” with warmth pulled north, cold air pulled south and various extreme events, for example, he said during the Wednesday panel discussion. “What is happening in the Arctic isn’t staying in the Arctic,” he said.

Sea ice loss, combined with the melt of land ice “that is contributing to sea-level rise, which influences everybody everywhere in the world,” shows how climate change in the Arctic deserves global attention, Holdren said. That, in turn, should spur global action in the south to protect the north, he said.

“As we all know, the most important single element of limiting the impacts in the Arctic and beyond is reducing the emissions of the gasses that are changing the atmosphere all around the world. And most of those emissions, of course, are not coming from the Arctic,” he said.

• Yereth Rosen came to Alaska in 1987 to work for the Anchorage Times. She has been reporting on Alaska news ever since, covering stories ranging from oil spills to sled-dog races. She has reported for Reuters, for the Alaska Dispatch News, for Arctic Today and for other organizations. This article originally appeared online at alaskabeacon.com. Alaska Beacon, an affiliate of States Newsroom, is an independent, nonpartisan news organization focused on connecting Alaskans to their state government.