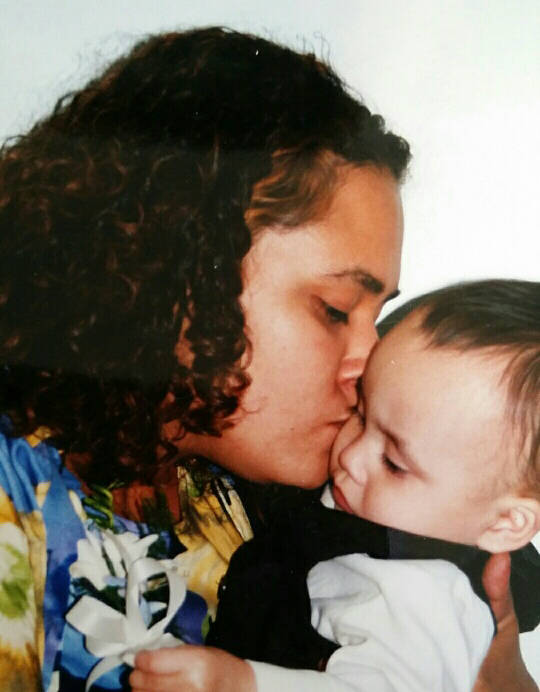

Even as a baby, Tanya was different.

Larry and Laura Rorem adopted Tanya when she was 8 months old in 1973, not knowing that Tanya’s mother had consumed alcohol during pregnancy. In the first few weeks they had Tanya, the Rorems knew something was a little off, but couldn’t put their finger on it.

“It was like she would shut down sometimes and she just, I couldn’t understand that sometimes there was this distance between us,” Laura said. “It’s hard to describe, but something wasn’t right.”

They didn’t get the answer to that question until 2003, when she was finally diagnosed with having a Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). The term serves as an umbrella for a variety of different birth defects that stem from a mother consuming alcohol during pregnancy. The effects of the disorders can be physical, mental or behavioral and can have lifelong implications.

For Tanya, the effects extended for her whole life. She lived in Juneau for much of her adult life, dealing with Schizoaffective disorder and substance abuse in addition to her FASD. She ran out of options in Juneau, her parents said, and moved to Anchorage to live in a group home.

This February, Tanya died in Anchorage of cancer at the age of 45. She had been homeless for most of the final 11 years of her life, her parents said.

[Our daughter lived with FASD for 45 years. This is her legacy]

Most people know that women are not supposed to drink while pregnant, Larry said. Most people know it can affect children, he said, but many of the effects continue into adulthood.

“The forgotten part of it is, kids with this grow up,” Larry said. “Society deals with them or doesn’t deal with them.”

Dwindling options

Estimates about how many people who have an FASD (in Alaska and elsewhere) are conservative because it’s an expensive and lengthy process to diagnose someone. Another factor is that mothers are often reluctant to disclose that they drank during pregnancy, which leaves many suspected cases as undiagnosed.

Juneau resident Mary Katasse, who has adopted three children with FASD, referred to FASD as an “invisible disease,” as the signs are hard to identify and diagnosing a patient is challenging. The Alaska Birth Defects Registry through the Division of Public Health estimated that from 1996-2011, about 113 of every 10,000 children born (a little over 1 percent) in Alaska were born with an FASD. The Alaska Mental Health Trust Authority writes on its website that the number of actual cases is much higher, and that Alaska leads the country in the rate of children born with an FASD.

Alaska has historically been progressive in treating FASD, but funding has decreased in the past decade. The Indian Health Service started screening women for alcohol-exposed pregnancy in the 1980s, and the state established the Alaska FASD Prevention Project in 1990 to study FASD.

Perhaps the biggest boost to statewide efforts came in 2000, when the state secured a five-year, $29 million grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to develop diagnostic teams throughout the state that provide training and curriculum development.

Some of those programs are still in use today, but the money has long since dried up. The money from the grant ran out in 2006, and as the state’s financial situation has worsened, funding for FASD services has run low.

According to numbers provided by the Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) Division of Behavioral Health (DBH), funding for FASD services in Alaska reached a peak in 2005 and 2006, when federal and state funds combined for $6.92 million in each of those years. In 2007, that number fell to $2.3 million, according to DHSS. Funding has plateaued at $1.01 million, according to DHSS, which has been the annual funding since 2015.

Marilyn Pierce-Bulger, the owner and manager of FASDx Services LLC, said this past year was the first time her diagnostic team was told that they were nearly through their budget. FASDx Services LLC helps diagnose FASD and help individuals with FASD figure out what kind of services they need. They help connect individuals with case managers who help manage daily services, but money for that is running out.

“That money is mostly gone, the case management piece,” Pierce-Bulger said, “and yet the need is huge. We continue to have huge numbers of individuals in the state who have FASDs who are not getting what they need.”

Teri Tibbett, advocacy coordinator for the Alaska Mental Health Board, said that with less money going into FASD-specific programs, those with FASD are forced to fit into other systems.

Many people with FASD who are getting help are relying on developmental disability services, behavioral health services or even the criminal justice system, Tibbett said. About 60 percent of adolescents and adults with FASD have trouble with the law, according to a 2004 study from researcher Ann Streissguth, and about 50 percent end up in detention, jail or psychiatric care of some kind.

One adult with FASD in Juneau, speaking anonymously, said he has gotten some services from REACH, Inc., but that the organization is better set up for people with more severe disabilities. Other than REACH, he said, there aren’t any services in town to help him find housing, work out his schedule, keep the house clean and assist with other daily needs.

He also mentioned the need for more individualized services. Every individual with FASD is a little bit different, falling somewhere different on the spectrum, so there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach.

Waiting for its day

Sandy Fiscus, who has been involved in numerous FASD efforts in Juneau, said the resources aren’t there anymore, but there’s hope for the future.

“There are way fewer options than ever before,” Fiscus said, “but there are many people in the state working toward positive things.”

Last year, for example, Fiscus and others organized a summer camp near Juneau for children with FASD.

The FASD Workgroup, created by the Governor’s Council, includes parents, service providers, community members and others who are working on a five-year plan. According to the Workgroup’s strategic plan, the vision of the five-year plan is to put initiatives in motion to increase education, training and overall FASD awareness.

Tibbett said education and awareness can help create a movement. Making more people aware of the problem, she said, could help to spur action.

“I think FASD is waiting for its day, like autism,” Tibbett said. “Autism went unrecognized and unserved, people with autism went unserved for many, many years and it finally reached a tipping point where people did recognize it.”

A large part of that, the individual with FASD in Juneau said, is making it clear to people that people with FASD aren’t all that different from those with autism.

“If you have FAS, there’s this bad stigma,” he said. “Everyone’s like, ‘Oh no, it’s FAS.’ But if it autism, it’s OK. I don’t understand that. It’s a traumatic brain injury. There’s something wrong with the way your brain is functioning (if you have FAS or autism). Why can’t people help the children who have FAS instead of labelling them as ‘bad kids?’”

Increasing awareness is a start, and he also mentioned the need for services for young adults to help them before they end up falling into the cycle of getting in trouble with the law that he’s seen so many others in town do.

Mary Katasse, raising three children with FASD, is looking uneasily at the next stage of life for her young children. She spoke specifically about her oldest son, who is 10.

“He’s going to start going through puberty and everything,” Katasse said. “We don’t have any training in that. We don’t have the support that I think we should have in each stage of life for someone with an FASD.”

• Contact reporter Alex McCarthy at 523-2271 or amccarthy@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @akmccarthy.