The northern seas were a dangerous place in 1917.

In the northern Atlantic, German submarines lurked beneath the waves and sunk ships into icy waters as World War I raged on.

In the waters around Alaska, all kinds of hazards awaited sailors. Blistering winds tossed boats on the waves, hidden reefs scraped against submerged hulls and blinding snowstorms led boats astray.

While the headlines atop the pages of Alaska newspapers at the time gave updates of war on the other side of the world, headlines near the bottom of the page told the stories of a tumultuous month in the waters of Southeast Alaska.

November of 1917 was a month of piracy, rescue, courtroom drama and a dash of war paranoia.

Thirty-six hours of mayhem

A well known Gold Rush vessel, the wooden steamer Al-Ki, was sailing from Juneau to Sitka when it ran aground during a storm on Nov. 1, 1917 near Point Augusta, on Chicagof Island about 26 miles southwest of Juneau.

According to a report from the Daily Alaska Dispatch, those aboard the Al-Ki quickly abandoned ship, leaving most of their baggage and valuables on board. Soon after the wreck, the sailors caught sight of an approaching vessel.

As the ship drifted closer, it came into clearer view. It was a 130-foot long, steel-hulled Canadian fishing vessel called the Manhattan. The crew of about 35 was heading to the Gulf of Alaska, as fishing was a year-round venture in those days.

Any hope that the sailors of the Al-Ki had of being rescued by this band of halibut fishermen quickly disappeared. As soon as they saw that the Al-Ki was abandoned, the crew of the Manhattan hopped aboard and began treating the boat like a rock band treats a hotel room.

“Trunks were hacked open with axes, valuable baggage slit with knives and the contents scattered over the vessel,” the Dispatch reported Nov. 11. “Even the Sitka and Petersburg mail was hurriedly rifled and the letters scattered to the mercy of the winds.”

These fishermen-turned-pirates spent nearly 36 hours looting the Al-Ki. No newspaper accounts explain why the sailors from the Al-Ki didn’t come to the defense of their belongings, but the crew of the Manhattan made off with blankets, coats and anything else they felt was of value on board.

The sailors from the Al-Ki watched as the Manhattan slipped away with their belongings, but karma was soon to catch up to the looters.

Terrors of the sea and land

Soon after the looting, another vessel passed by Point Augusta. This time, the stranded Al-Ki sailors were in luck.

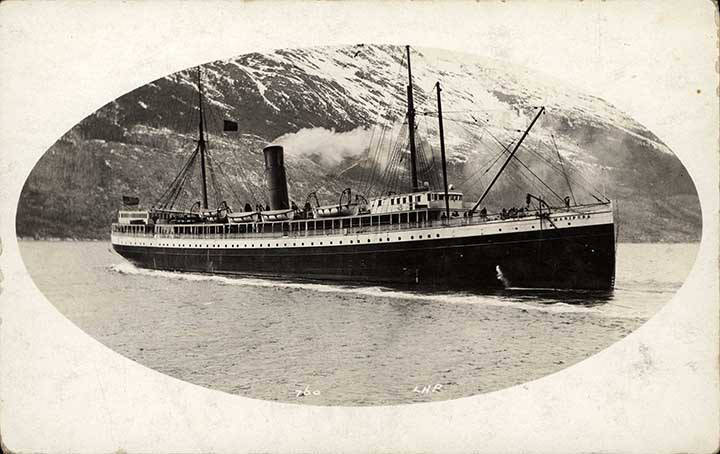

The boat, a large steamer, was called the Mariposa. It picked up the stranded sailors and took them safely to nearby Hoonah. Immediately, the Al-Ki sailors told the story of what they had seen and a message was sent out all over Southeast Alaska: Find the Manhattan and the looters on board.

On Nov. 15, the job of searching for the Manhattan became much easier. During a thick snowstorm, the fishing vessel struck an uncharted rock near Lituya Bay.

The crew disembarked the sinking ship and headed toward the shore. As they quickly found out, the hazards of the Alaska shoreline weren’t limited to the icy seas.

They made it to shore, but they were incredibly unlucky with their landing spot. As the boats pulled ashore, an enraged brown bear charged out of the brush. In his book, “Land of Ocean Mists,” Francis E. Caldwell tells the story.

“They were well acquainted with the perils of the sea,” Caldwell wrote, “but bears were something else.”

The crewmen were able to escape the clutches of the bear, even after the bear swam after them some ways after they had gone back to sea.

Coincidentally, the first vessel to find one of the Manhattan’s boats was the Mariposa, the rescuer of the Al-Ki sailors not even two weeks earlier. The Manhattan sailors climbed aboard, elated to be saved, when they were immediately arrested for the looting of the Al-Ki.

Marine misfortune

The men were tried the following week, with a few sailors from the Al-Ki boating over to testify against the accused looters. A.H. Humfrey, an agent for the company that owned the Al-Ki, testified that he was appalled when he saw the damage to the ship.

“Not only had the vessel been looted but there was every evidence of deliberate plundering and mutilation,” Humfrey testified, according to a report in the Dispatch. “Even the piano had been turned over and the keyboard kicked to pieces.”

Two pieces of baggage taken from Manhattan crew members were presented to the court, appearing to contain the Al-Ki purser’s coat and napkin rings that appeared to be from the Al-Ki.

R.A. Gunnison, assigned as the defense for the Manhattan crew members, painted a different picture. He argued, with testimony from the Manhattan crew members to back him up, that the sailors did indeed take items from the Al-Ki, but only to save them from falling into the sea with the doomed vessel.

As the two crews bickered in court, news came to Juneau about the ship that was responsible for rescuing both of them: the Mariposa had been lost. On Nov. 18, it crashed on a reef near Point Baker (which is now called Mariposa Reef). The string of marine misfortune had continued.

Lost in the waves

The trial of the Manhattan looters was put on hold shortly after the wreck of the Mariposa, and the story faded from the headlines.

All of the talk was about the Mariposa’s wreck, which was a loss of an estimated $2 million in terms of vessel and cargo, according to the Dispatch. Like the wrecks of the Al-Ki and the Manhattan, there was no loss of life. After another vessel, the Spokane, went down in what was described as “mysterious circumstances,” the murmurs turned into a frenzy.

The headlines of war stories and shipwrecks began to converge. A story from the International News Service on Nov. 27 said that survivors from the Spokane had apparently been on other ships that had gone down, and that they felt they had been victims of acts of war.

“Some of the survivors, who have been in three wrecks in as many weeks, declare openly that German agents are responsible,” the report read.

A 27-year-old German named Carl Elze was arrested in Seattle soon afterward, only to be released quickly. Carl Wiltsche, a 29-year-old Austrian and Spokane crew member, was arrested not once but twice. Nothing came of the arrests, but the very fact that the arrests were made showed that despite the Pacific Northwest’s isolation, war fever had certainly made its way to the Last Frontier.

For those in Juneau, that fever seemed to have abated their anger at the 35 Canadian fishermen who remained in jail. The Manhattan crew members had been remarkably unlucky during their trip through Alaska’s seas — from uncharted rocks to enraged brown bears to being stuck in jail — but they did get very fortunate in one important sense.

The evidence that was presented at trial, according to Juneau District Attorney Smiser, wasn’t enough to convict the crew members. News of Smiser dismissing the trial only took up one paragraph in the Jan. 13, 1918 edition of the Dispatch.

The crew members of the Manhattan, who were at the mercy of the Alaska weather and wildlife for their whole bizarre journey, were bailed out in the end, as the evidence of their crime was erased by the ever-treacherous waters and shore of the Alaska coast.

^

References

“Shipwrecks of the Alaskan Shelf and Shore,” by Evert E. Tornfelt and Michael Burwell

“Land of Ocean Mists,” by Francis E. Caldwell

“Can’t Find Fish Boat,” Daily Alaska Dispatch, Nov. 11, 1917

“Manhattan’s Crew Must Face Charge,” Daily Alaska Dispatch, Nov. 17, 1917

“Mariposa’s Commander Had Hunch,” Daily Alaska Dispatch, Nov. 20, 1917

“Manhattan Case Today,” Daily Alaska Dispatch, Nov. 22, 1917

“Manhattan Case Will End Today,” Daily Alaska Dispatch, Nov. 23, 1917

“Wrecking of Ships Regarded Suspicious,” International News Service, Nov. 27, 1917

“Al-Ki Looting Case to be Finally Dismissed,” Daily Alaska Dispatch, Jan. 13, 1918

• Contact reporter Alex McCarthy at 523-2271 or alex.mccarthy@juneauempire.com. Michael Burwell, co-author of “Shipwrecks of the Alaskan Shelf and Shore,” contributed research to this article.