In 1869, two years after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia, the U.S. Coast Survey’s George Davidson departed Sitka with a small party of men in large cedar boats. His task was to observe a total solar eclipse, predicted to take place Aug. 8 of that year, between the mountains and glaciers of the Chilkat Valley.

As the oldest scientific organization continued by the federal government, the U.S. Coast Survey observed all kind of natural phenomena. Davidson was given instructions to observe the eclipse no matter what, but he knew he needed help. So he enlisted celebrated Tlingit leader Kohklux — known as Shotridge to much of the world — to lead the expedition.

The party paddled to Klukwan, the capital of the Chilkat River Valley at the head of Lynn Canal. Davidson, Kohklux and his wives struck up a friendship (Kohklux was married to two sisters from the Stikine River Tlingits). After the eclipse, Kohklux and his wives provided Davidson a map of the Tlingit Chilkat Valley in exchange for a diagram of the eclipse. It was a token of friendship that would inform American maps for decades.

But Kohklux’s name was never credited as an author of the Coast Survey maps, which relied on his work. The original map — which spanned 500 miles and took three days to draw — would sit virtually untouched in an archive for 141 years. Thanks to work from an independent historian of cartography and geography, Dr. John Cloud, Kohklux’s map was brought back out to public attention in 2007. He has been working on this research for the past 12 years.

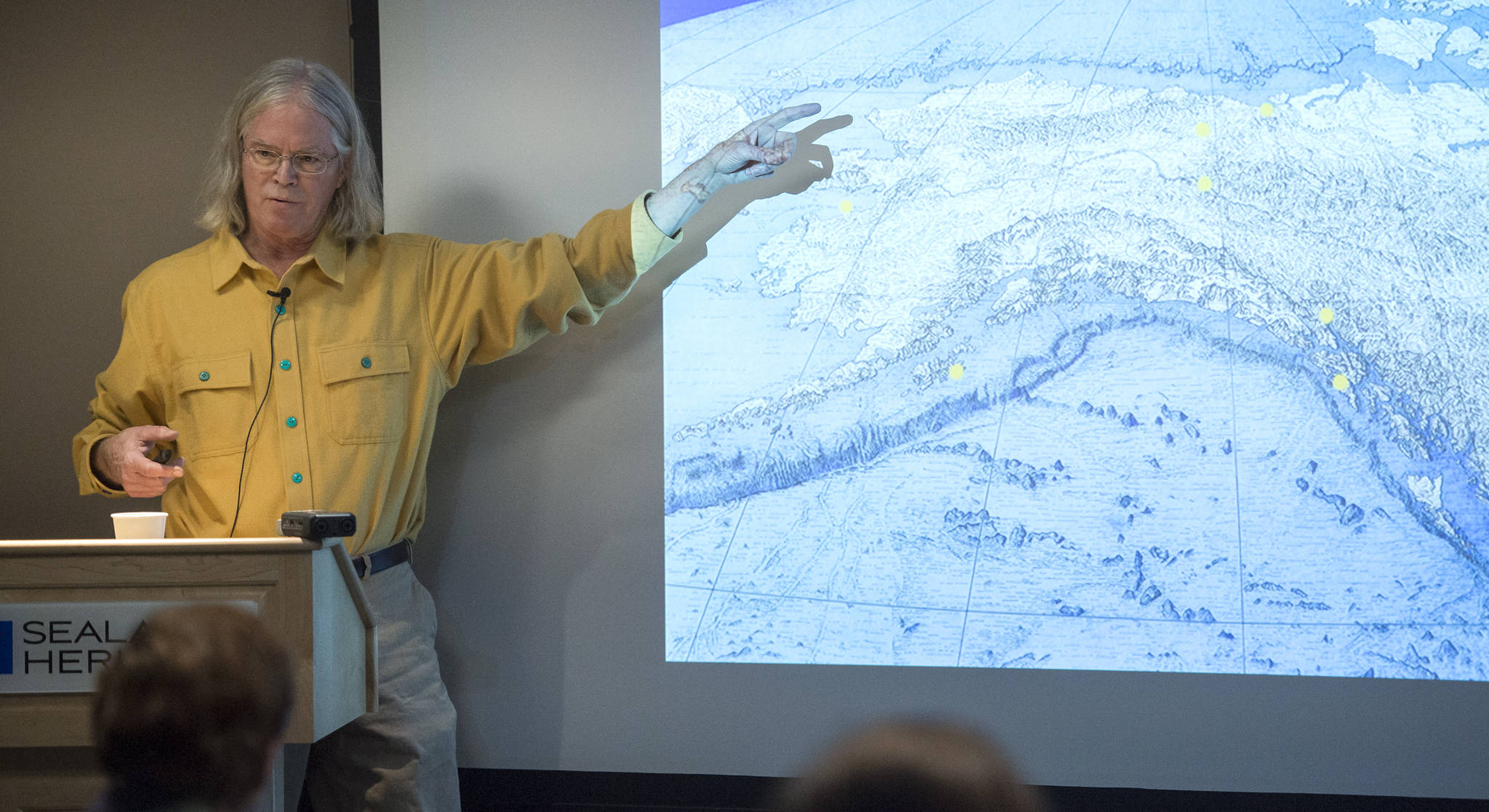

Kohklux and his wives’ map was just one of many forgotten additions to the early mapping of Alaska, Cloud explained at a Wednesday lecture at the Sealaska Heritage Institute. Many would be forgotten. Placing credit where credit is due — as well as unravelling a great mystery — is what drove his research, which was recently published in the Expedition magazine.

“The names and lives you put on a map are important … but equally important are the names you don’t put on a map,” Cloud said, banging a hand on the lectern at SHI for emphasis.

Cloud dug through archives at universities across the country to make his findings. Some hadn’t been touched in decades, including an archive of photographs which sat in boxes under a staircase at the California Academy of Sciences for decades. He worked his way through dusty archives at Dartmouth, U.C. Berkeley, University of Washington and Iowa University. Much had been lost to time or damaged.

“Everything was scattered to the wind,” Cloud said.

In addition to Kohklux’ map, Cloud unearthed another lost work of indigenous cartography: a detailed map of the nearly 700 miles of the 2,000-mile long Yukon River. That was drawn from memory by a man named Joe Kakryook, an Esquimaux native of Port Clarence. Kakryook detailed every village, every bend in the river.

“It was unlike anything I had ever seen,” said Cloud, a former employee of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, the modern day incarnation of the U.S. Coast Survey. Kakryook’s map would be invaluable to defining the eastern boundary between Alaska and Canada.

Many early boundaries of Alaska were defined verbally by explorer Vitus Bering, a Danish cartographer and explorer in the service of the Russians. So when America purchased, or in Cloud’s terms “pretended to purchase” Alaska from the Russians, who “pretended to own it,” the U.S. Coast Survey was tasked with defining those boundaries scientifically. They depended on Alaska Natives like Kakryook and Kohklux and his wives to navigate Alaska’s vast new addition to the country.

Cloud said it’s time their contributions are honored.

“Whoever Shotridge, Joe Kakryook and his wife were, they deserved better,” Cloud said.

• Contact reporter Kevin Gullufsen at 523-2228 and kevin.gullufsen@juneauempire.com.