The trans-Alaska Pipeline System is still 100 percent full.

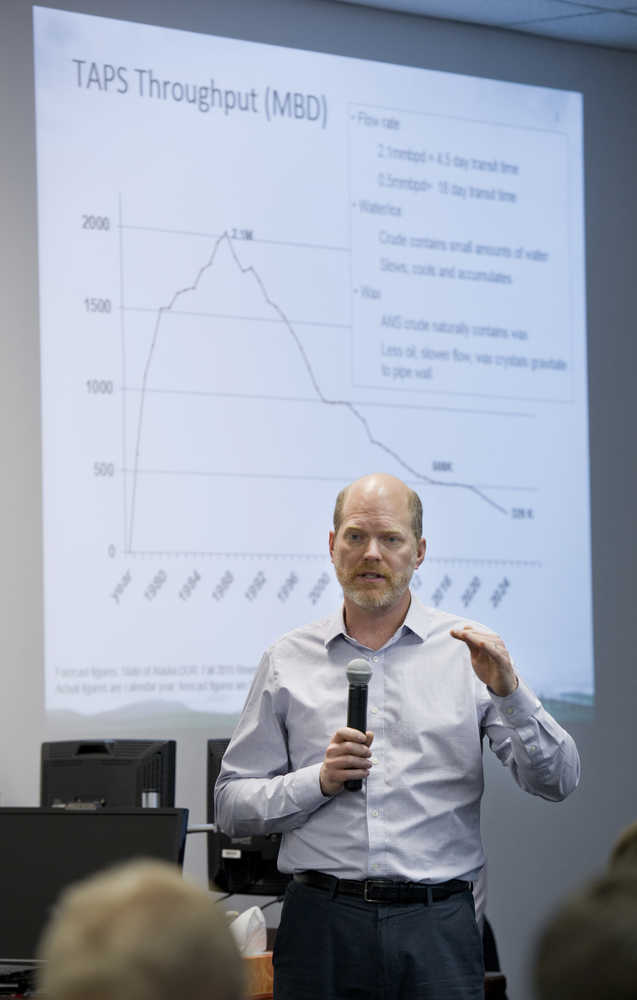

The speed of oil flow, not the amount of oil in the 39-year-old pipeline, is the issue creating engineering challenges for Alyeska Pipeline Service Company, engineer Rob Annett told legislators and members of the public during a Tuesday “Lunch and Learn” presentation at the Alaska Capitol.

Alyeska operates the 800-mile trans-Alaska Pipeline System on behalf of the major North Slope oil producers, which own shares of Alyeska.

In the early 1980s, when the pipeline shipped 2.1 million barrels of North Slope crude oil from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez every day, it took four days for oil to travel the length of the line. Today, thanks to lower production in Prudhoe Bay, it takes 18 days.

The pipeline was designed to run full, not like a sewer or storm drain that only fills when it rains. To keep its pumps and valves running properly, the pipeline has to stay full of oil. As production has fallen by an average of 5 percent per year over the past decade, that engineering need has resulted in slower flow, creating problems, Annett explained.

When it comes out of the ground at Prudhoe Bay and enters the pipeline, North Slope oil is piping hot at 110 degrees. As it travels toward Valdez, it passes through some of the coldest regions of North America, and the oil cools rapidly. At 18 days’ travel time to Valdez, the oil is moving slow enough that it would drop below the freezing point without additional effort by Alyeska. If that were to happen, ice could build up in the pipeline, blocking valves or gates.

“The challenges the TAPS faced for getting to 2.1 million barrels a day … kind of pale in comparison to going low,” Annett said.

To keep that worst-case scenario from happening, Alyeska has an engineering group dedicated to keeping the oil flowing at low temperatures and lower volumes. Alyeska has even built two test loops of pipeline in Oklahoma to examine what might happen under different conditions.

To immediately solve problems, Alyeska has gone to enormous effort to build a facility in the Interior that reheats the oil as it travels from north to south. It also puts some oil in a loop, pumping it several times in order to heat it before returning it to the pipeline.

Above all else, Annett said, the goal is to keep the pipeline in a “steady state” throughout the winter. That means the oil keeps flowing and moving, the better to avoid ice buildup.

“The moment you stop, then you start to cool down,” he said.

As an emergency option for a midwinter cold-snap pipeline shutdown, Alyeska also has installed methanol injectors at points along the pipeline. If the oil temperature drops too low, those injectors could dump methanol into the pipeline and get rid of the ice. That might save the pipeline, but it would contaminate the oil within, possibly making it worthless (or worth less) to refiners.

Even without a catastrophic ice buildup, Alyeska is continuing to cope with wax within the pipeline. North Slope oil contains about 2 percent heavy, high-carbon wax, and at low temperatures, this wax crystallizes on the walls of the pipeline.

“As we were doing this, with the slowing crude oil and colder flow, we were seeing more and more wax,” Annett said.

Scraping tools called “pigs,” which are propelled by flowing oil, travel through the pipeline to remove the wax, but it’s a laborious process. Pictures shared by Annett showed wax-covered pigs, removed from the pipeline, looking like the Q-Tips of a coal miner with a hygiene problem.

Alyeska is developing new pigs, including one that would pressure-wash the pipeline’s interior with streams of oil or liquid to remove wax.

While Alyeska is now shipping oil far below levels envisioned when the pipeline began operating in 1977, Annett said there is a limit to how many engineering tricks and techniques the company can develop. Below a certain level of flow, the oil will move so slowly that operating the pipeline becomes impossible.

“If we don’t address that (throughput), then we’ve got to start looking at pretty creative stuff to get out of this deal,” he said.

When will Alaska reach that critical level?

He doesn’t know.

“We do have indications there is a number, we just don’t know what it is,” he said.

This story has been corrected to state that Alyeska operates the pipeline but does not own it; ownership of the pipeline is split among a handful of subsidiaries controlled by the major North Slope oil producers.