Alaska is still likely to lose money on the Willow oil project during its initial years, but not as much as predicted last month, according to a new assessment by state officials presented to lawmakers Thursday. But Alaska’s oil tax laws are so complex and there’s so many unknown variables it’s possible the actual outcome will be wildly different.

The presentation followed a Department of Revenue report in February that the Willow project approved by the Biden administration earlier this month — controversial in itself and being challenged in lawsuits by environmentalists — would result in the state losing more than $1 billion in oil production tax revenue during the next decade. The revised figures presented Thursday show a $366 million loss for the state through 2027, after which it would show increasing annual surpluses during the next five years before settling into a long-term decline.

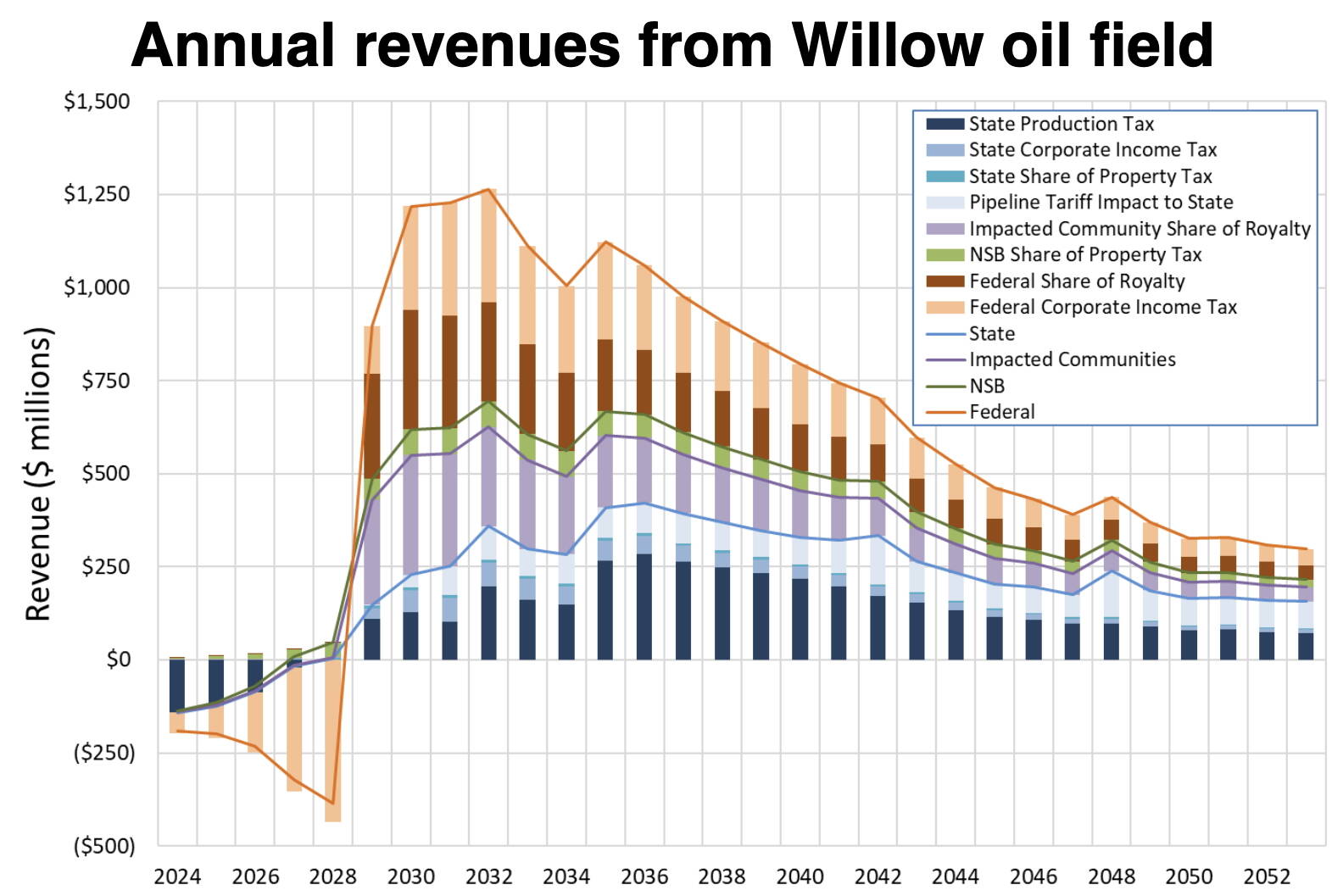

“We see break-even for state revenues in 2030 under the current assumption with a 30-year cumulative revenue of $6.3 billion to the state,” Owen Stephens, a commercial tax analyst for the revenue department, told the Senate Finance Committee. “We also expect billions of cumulative revenue for local communities on the North Slope, for the federal government and for the producer.”

The updated projection shows about $10 billion in total revenue for ConocoPhillips as the developer, $6 billion for the federal government and $3.5 billion for North Slope communities.

The previous report projected the state would surpass the break-even point on Willow around 2035 and earn $5.4 billion during the life of the project.

Revenue officials said Thursday that last month’s projections were based on simplified data that didn’t take into account all aspects of the state’s tax structure during Willow’s upcoming development phase, such as the “minimum tax floor” for companies that limits how much they can claim in exemptions for things such as construction costs.

Also, a state revenue forecast released Tuesday showing significantly lower oil prices than forecast last fall will affect the oil taxes the state can potentially collect — although that also means a worse overall financial outlook for the state’s finances.

The state is already facing deficits of hundreds of millions of dollars in its annual budgets, and the updated revenue forecast means there is a shortfall of more $1.1 billion in budgets for this year and next submitted by Gov. Mike Dunleavy.

The state has about $2.5 billion in its Constitutional Budget Reserve. Legislators are also discussing proposals involving Permanent Fund earnings, expected to account for 48% to 64% of total revenue during the next decade, that direct a larger share towards state spending rather than dividends for residents.

Supporters of the Willow project in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, including the Dunleavy administration and the entire Alaska State Legislature, call it a vital element of the state’s long-term financial stability as production from existing North Slope fields continues to decline.

“The Willow project represents essentially a new era in the state of Alaska,” John Crowther, deputy commissioner for the state Department of Natural Resources, told the Senate Finance Committee. “The project especially is very significant in terms of production, employment and investment. But really it’s the maturation of a trend.”

Production at Willow, if it begins during the 2029 fiscal year, is expected to achieve a peak production of 183,000 barrels of oil a day in fiscal year 2030, and then quickly and steadily drop during its lifetime with a total of 613 million barrels of oil extracted by 2053, according to Thursday’s presentation. Stephens told the committee such a declining curve is typical for North Slope production.

The approval of Willow, the largest new project in two decades, may pave the way for other new projects companies hold leases for and which might not fall under new environmental restrictions announced by Biden at the same time as his approval of Willow. Crowther said the scope and potential financial benefit to the state might in theory be comparable to the impact of Prudhoe Bay.

But he emphasized there are still plenty of obstacles ahead, including the environmentalists’ lawsuits. In part due that legal uncertainty, ConocoPhillips not yet committing to a final investment decision.

“Projects of this scale and complexity are never assured,” Crowther said. “In some ways it’s perhaps even fair to say they’re fragile.”

The Willow field, located to the west of existing projects, is distinct from them because it is entirely on federal land, which means the state won’t receive royalties from oil production — instead they will essentially be split between the federal government and North Slope communities. State revenue will consist of taxes on production, corporate income and property, plus tariffs on the Alaska Pipeline.

A motion to intervene in one of the two lawsuits against Willow was filed by the state on Thursday, arguing among other things the oil field could spur additional projects on adjacent state land “leading to additional royalty and taxes for the State.”

Altering the state’s tax rules and other regulatory aspects of oil projects is something the Senate Finance Committee has discussed “many, many times” over the years, said Sen. Bert Stedman, a Sitka Republican who co-chairs the committee.

“We have one of the most, if not the most, complex oil tax structures on the planet we’ve been told by our consultants,” he said. “Most of them would prefer that we simplify.”

• Contact reporter Mark Sabbatini at mark.sabbatini@juneauempire.com