JOINT BASE ELMENDORF-RICHARDSON — Alice Tanaka Hikido clearly remembers the bewilderment and sense of violation she felt 74 years ago when FBI agents rifled through her family’s Juneau home, then arrested her father before he was sent to Japanese internment camps, including a little-known camp in pre-statehood Alaska.

The 83-year-old Campbell, California, woman recently attended a ceremony where participants unveiled a study of the short-lived internment camp at what is now Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Anchorage.

Archaeologists working on the research used old records to pinpoint the camp location in an area now partially covered by a parking lot. The Army study is expected to be finalized later this year.

“As I look back, I had no idea as a child that the U.S. and Japan were having difficulties,” Hikido said. “It was a tremendous surprise to me.”

Hikido herself was interned at Idaho’s Minidoka camp with her mother, younger sister and two brothers a few months after her father’s arrest during one of the nation’s darkest chapters — the forced incarceration of tens of thousands people of Japanese ancestry, including Americans, during World War II.

Her father eventually joined his family in Idaho in 1944. They spent more than a year there together before the war ended and they returned to Juneau.

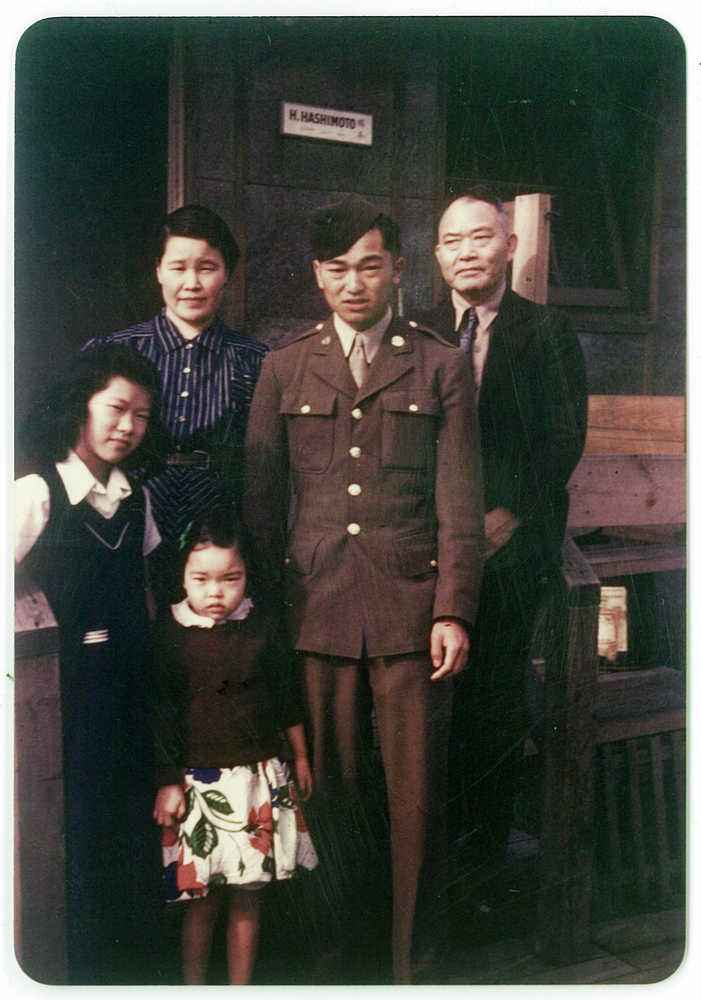

Her father, Shonosuke Tanaka, was among 15 Japanese nationals and two German nationals who were rounded up in the territory of Alaska almost immediately after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

That number would grow to 104 foreign nationals, mostly Japanese, who were arrested in Alaska as alien enemies. An estimated 145 others, including some Alaska Natives who took Japanese names in marriage, also would be sent to internment camps outside the territory under Executive Order 9066, which launched the exile of about 120,000 Japanese-Americans.

Before leaving Alaska, Tanaka and 16 other men were briefly housed at the Anchorage Army post formerly known as Fort Richardson.

Archaeologists recently zeroed in on the site based on documents including a map and the only two known photographs, according to Morgan Blanchard, a local archaeologist who worked on the study.

“Although it was known that this camp existed — it shows up on all the lists of camps that existed during the war — no information was available,” Blanchard told a small crowd during a Feb. 19 Day of Remembrance ceremony at the base. “So we filled in a lot of the blanks.”

Researchers discovered debris such as .30 carbine rounds and barbed wire fragments at the site, but they were unable to find anything definitely connected with the camp, Blanchard said. Researchers believe — but can’t say with certainty — that the 17 foreign nationals who were sent to the post were actually held at the camp, constructed between February and June 1945.

It was only after her father joined them in Minidoka that Alice Hikido and her family heard his story for the first time, from his apprehension in Juneau to various internment camps including at least one in New Mexico.

The family’s time in captivity forced the closure of her father’s Juneau cafe. They reopened it upon their return, with the help of a welcoming community.

Hikido and her 75-year-old sister, Mary Tanaka Abo, are the only surviving members of her family who experienced the internment.

Today, Hikido sees the same distrust of some foreigners that her family experienced so many decades ago. It’s troubling to her to hear politicians whipping up that fear by demonizing certain minorities.

If there’s a lesson to learn, she said, it’s how crucial it is for individuals to arm themselves with knowledge.

“It’s incumbent upon citizens to be well-informed,” Hikido said. “If you’re well-informed, then fear doesn’t overcome your better judgment.”