By Forest Wagner

Earlier this spring I had the great privilege of skiing from Knik Lake to McGrath on the Iditarod Trail. Conditions were warm, glide was good, and the usual human-moose showdown never occurred. At one point, nearing exhaustion on Day 5 and about 15 miles from the Dene village of Nikolai, aurora burned so brightly time stopped. Fellow time traveler John Muir recalled in 1890, in near religious ecstasy, that when aurora burst across the sky in Glacier Bay’s West Arm, “the blessed night circled away in measureless rejoicing enthusiasm.” Aurora, like so many improbably magical things in the natural world, helps me place myself as a very small part of something so much larger. Back on the trail and rejuvenated by the northern lights, with temps hovering around minus 10 degrees Fahrenheit, I kicked it in through the subarctic night, rested briefly in Nikolai, then finished the ski, gliding in the following evening to the Interior hub of McGrath.

Writing this column now for the UAS Sustainability Committee, I am still awash in notions of time and space. What took me six and half days under my own power, some 315 miles of varied topography ranging from the tidewater of Knik Inlet to Rainy Pass to the oxbow bends of the Kuskokwim river, was quickly repeated by a Cessna Caravan in an hour and half. Flying over Alaska that late afternoon a month ago, its frozen bogs and rivers quickly fell away to the sweeping granite and glaciers of the Alaska Range. Light at acute angles, whether in high latitude places or at twilight, like aurora creates similar time stopping magic. Muir, our original nature worshipper, visited me again, twanging from the glacial landscape of the Cassier and Coast mountains in 1879, that “here, too, one learns that the world though made, is yet being made; that this is still the morning of creation.” Alpenglow on the Alaska Range buoyed our plane into a freshly blanketed Anchorage evening, where a foot of snow had fallen the day before.

Time passes. Almost 52 years ago on April 22, 1970, following a decade of civil rights tension and eventual federal legislation, the United States celebrated its first Earth Day. The brainchild of Wisconsin U.S. Sen. Gaylord Nelson, that first Earth Day galvanized environmental activism and created the political pressure needed for the passage of the Clean Water Act and the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Now an international event, Earth Day has helped communicate concepts like ecological scarcity and global carrying capacity to generations.

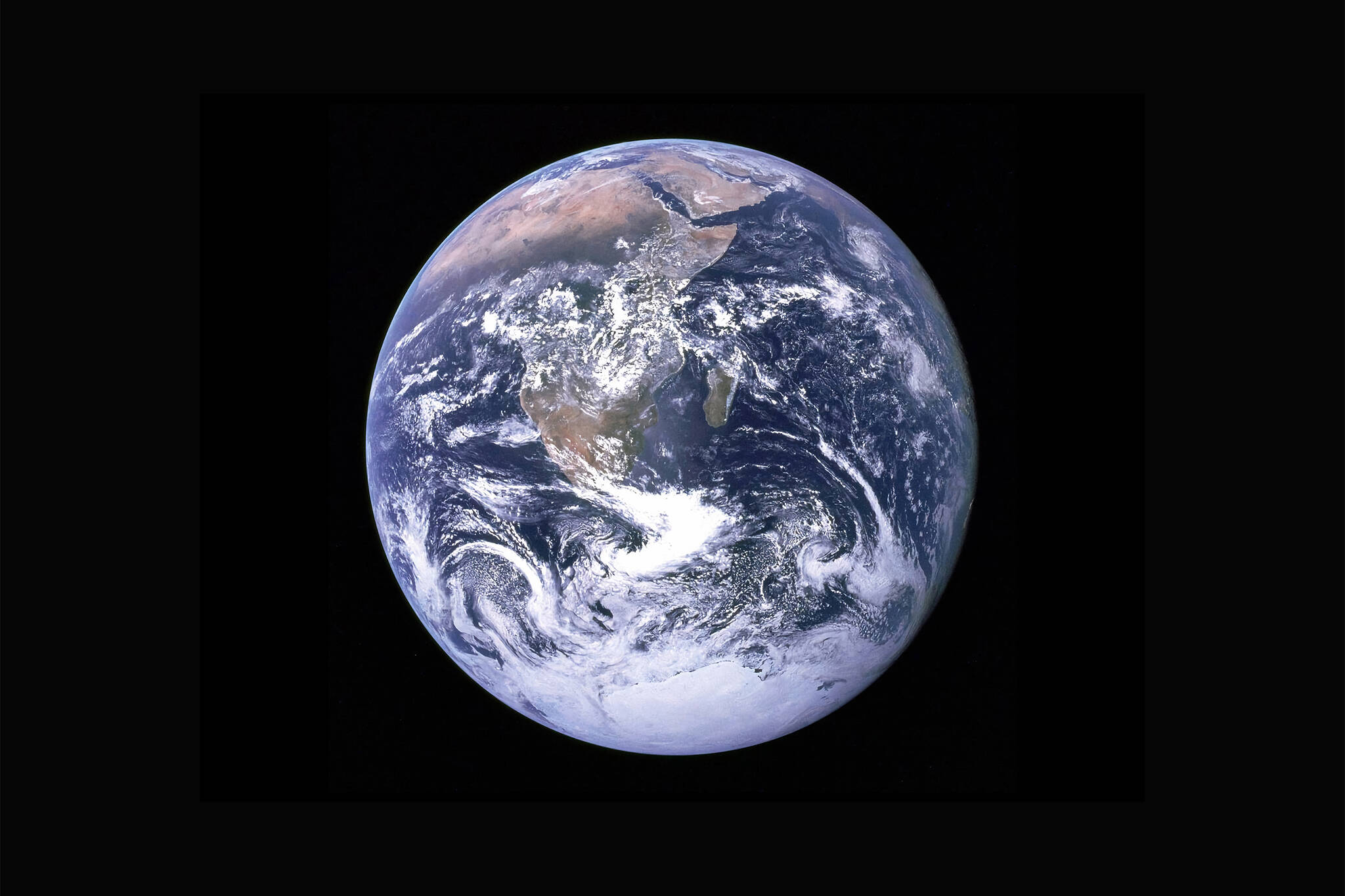

Thinking of our planet in a cosmic way is a powerful imaginary that relates well to my musings about the magic of time and space. Astronaut Bill Anders’s photo, Earthrise, snapped on Christmas Eve 1968 while in orbit around the moon on the Apollo 8 mission, was the first color image taken of our planet. Realizing the captivating potential of the photo, Nasa released the image just two days after Apollo 8 returned to Earth. The Earthrise image, by actually showing the blue earth and its atmosphere, small and distant in relation to the austere lunar surface of the Moon, gave early environmentalism a planetary symbol to cohere around.

Space, then, becomes a story about time. Although recent advances in telescopes are magnifying what astronomers can see, there is no other planet so far discovered in space that supports life. Yes, geoengineering and space colonization may in time prove useful options for human society. But for now, we’re still uniquely Earthlings, living on a magical and singular planet, more connected to each other and our more than human world than ever before.

Times are changing and we sit at a crossroads. In this time of renewed geopolitical tension, I stand with the people of Ukraine, and independent democracies everywhere, and sincerely hope to live someday soon on a planet where we can adjudicate our differences peacefully. Consider celebrating Earth Day this year by recycling, using reusable grocery bags, picking up trash, urban gardening, or simply talking with a friend about your climate change related hopes and fears. I’m offsetting my air travel, https://juneaucarbonoffset.org, and it’s surprisingly inexpensive.

Thanks for reading this, Juneau, and happy spring.

• Forest Wagner is assistant professor of outdoor studies. Wagner is a member of the University of Alaska Southeast Sustainability Committee. The views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Alaska Southeast. “Sustainable Alaska” appears monthly in the Juneau Empire.