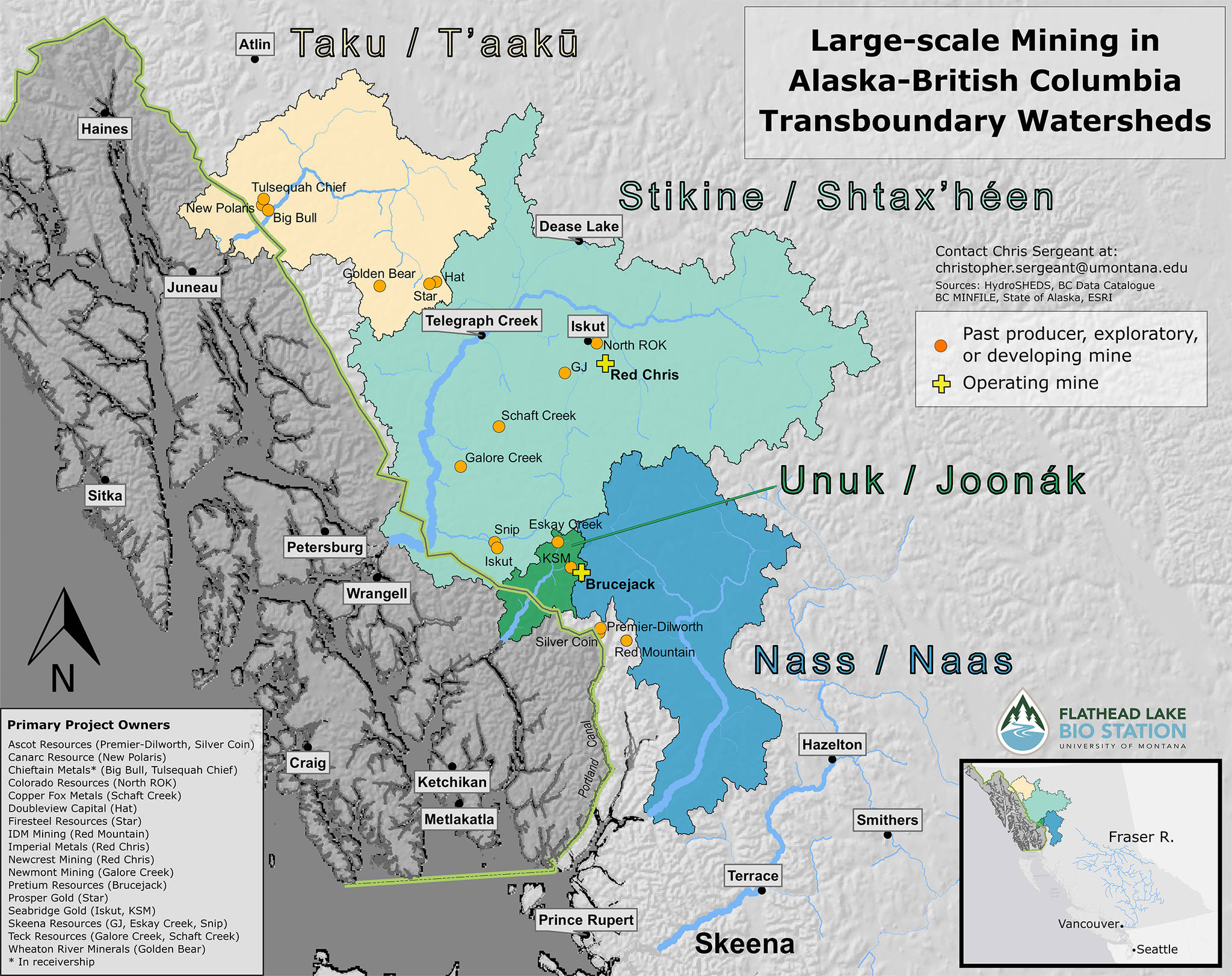

The proposed and ongoing development of dozens of large-scale mines in Alaska and British Columbia is the subject of much controversy.

While many people are excited by the economic opportunities, others are concerned about the negative effects of these industrial projects on our river systems — particularly to salmon and the cultural, economic and other natural systems that rely upon them. However, I bet that almost everyone would agree that we should protect the integrity of salmon ecosystems, with or without mines. So how can we decide whether to support or oppose these development projects?

[Sustainable Alaska: Vote for the trees and stop recycling bad ideas]

Last week, I participated in a workshop in Montana aimed at advancing scientific knowledge of mining impacts on salmon-bearing watersheds. The group of 40 experts from the U.S., Canada, Tribes and First Nations included salmon biologists, stream ecologists, ecotoxicologists, hydrologists, geochemists, engineers and natural resource managers from universities, governments and non-governmental organizations. We spent three days discussing how mines impact salmon and the river systems they rely on. Importantly, we identified the areas where our lack of knowledge, or lack of implementation, may result in poor outcomes for salmon.

While the topics — spanning science and policy — were complex, the consensus was simple: Examples around the world show that mining has caused real harm to fish. Mines, permitted and operated the way they have been to date, can create long-term and often permanent damage to the land, water and connected ecosystems and cultures.

This knowledge underscores the fact that we are at a critical juncture. The transboundary watersheds bordering the Gulf of Alaska host the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world, and the clean, free-flowing rivers that course through them support one of the largest and healthiest salmon populations left on the planet.

With that backdrop, our workshop concluded that both the U.S. and B.C. currently have: (1) an incomplete consideration of potential and ongoing impacts from mining in Alaskan and transboundary watersheds; (2) incomplete planning for chronic pollution releases and catastrophic failures; (3) a lack of full consideration for project alternatives, such as less destructive designs; and (4) a lack of independent, transparent, and peer-reviewed scientific research.

Therefore, the true risks involved with these proposed and/or permitted mining operations are being consistently underestimated.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. We agreed that science needs to be more effectively incorporated into the mine permitting process. That is, the policies governing mine permitting need to: employ the best available scientific methods and information, including indigenous science, to accurately determine the nature of and risk to a watershed; fully address how any risks can be mitigated; and close any critical knowledge gaps before permits are issued. Importantly, all this needs to be done following rigorous and defensible scientific protocols.

Evaluation of potential impacts is even more complex when watersheds span multiple jurisdictions, as is the case for the many transboundary rivers on the US-Canadian border. There is currently no consistent method of evaluating mining projects in rivers that cross political borders. This too needs to change.

The decisions we make today about these watersheds are important because they will affect not only us but also the health and viability of salmon, humans and everything in between for countless future generations. One of the workshop attendees, a member of the Taku River Tlingit, told me about her people’s custom of always keeping an open seat at the table for the salmon, the bear, the caribou. Imagine how this would influence our decisions if we all did that as well. Mine development decisions must consider who is benefitting (and who is not), both now and in the distant future.

The Montana workshop attendees agreed that there is an urgent need for using the best science, which is currently not being done. If a mining operation plan can be proven to be capable of sustaining the health and integrity of a watershed in perpetuity, then let’s move ahead. If not, we need to go another direction. The salmon might not have a seat at the table, but they are depending on us to do the right thing.

• Sonia Nagorski is an assistant professor of Geology at the University of Alaska Southeast and is a member of the UAS Sustainability Committee. “Sustainable Alaska” is a monthly column, appearing on the first Friday of every month. It’s written by UAS Sustainability Committee members who wanted to promote sustainability. The views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Alaska Southeast.