Richard “Dick” Willoughby was the kind of person to gaze into a raincloud and see the sun.

One of the most colorful characters in Juneau’s early days, Willoughby liked to tell tall tales and was especially fond of entertaining visitors. His obituary in the Yukon Sun from May 18, 1902, described one way he interacted with tourists.

“When they complained of the rain in Juneau he would stand in the worst downpours and declare, as he looked up to the clouds, that it was the driest place on earth, and he never knew it to rain there in thirty years,” the obituary read.

Willoughby, the namesake of Willoughby Avenue, didn’t limit his unnatural observations to quick jokes on the street. In the late 1880s, Willoughby pulled off his grandest of pranks: the tale of the “Silent City.”

The mirage

Willoughby was already a middle-aged man by the time he arrived in Juneau in 1880. Born in the early 1830s in Missouri, Willoughby ended up in Alaska in search of gold.

Thomas Arthur Rickard’s 1909 book “Through the Yukon and Alaska” says Willoughby arrived in Juneau (which was called Harrisburg at the time) just after Tlingit Chief Cowee guided Richard Harris and Joe Juneau to gold in 1880.

The smooth-talking Willoughby quickly earned friends and admirers in town, earning the nickname “Uncle Dick.” Rickard described Willoughby as a lovable type with “a long white beard and a resonant voice.” Some eventually referred to Willoughby as “the Professor.”

An article in the June 1897 issue of “Popular Science” details the way Willoughby tricked his way into Alaska’s history. The article, written by David Starr Jordan, states that Willoughby came to friends in Juneau in midsummer 1888 with a story so unbelievable that it had to be true.

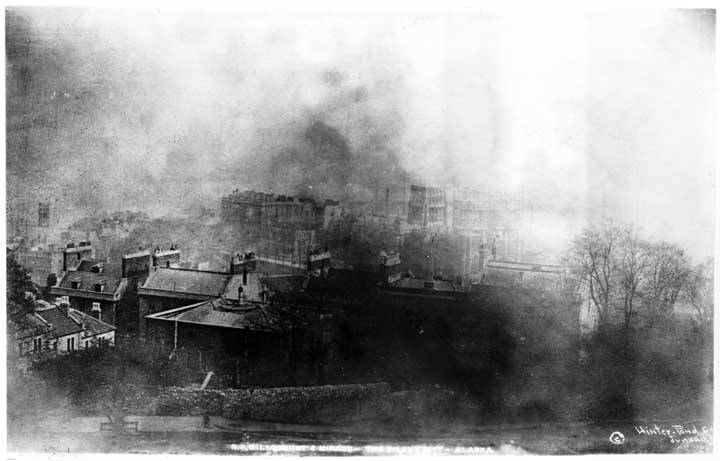

He had been to the Muir Glacier at Glacier Bay on the longest day of the year, June 21, and he had seen a mirage. The hazy image of an entire city was floating above the glacier, Willoughby claimed, complete with brick and stone houses, elm trees, a tower with scaffolding around it and even a river in the background.

The bearded trickster referred to this as the “Silent City,” and believed it to be from some far-off place.

Willoughby had seen the mirage of the city before, he said, always in late June, but this time he was fortunate enough to get a photograph. He produced the negative of the photograph, and people rushed to make copies of the picture.

Willoughby refused to reveal much about his photography process, saying that he had to use a very long exposure and that he developed the negative using a “secret process” that somehow involved sunlight.

Even those who were skeptical of Willoughby’s story knew this could be an opportunity to get visitors from down south to visit Southeast.

“An association of local men was formed at Juneau for the purpose of exploiting the discovery and of selling the prints struck of Willoughby’s wonderful negative,” Rickard wrote.

The small copies of the photograph were sold for 75 cents each, Jordan wrote, and were distributed far and wide. Jordan himself bought one in Sitka in 1896, he wrote.

On the back of the photos, a long passage described Willoughby as an innovative explorer, giving him credit of being the first American to find gold in Alaska’s icy peaks and “tearing from the glacier’s chilly bosom the ‘mirages’ of cities from distant climes.”

The farce of the Silent City had only just begun, as a bizarre expedition the next summer only furthered the legend of the mirage.

The expedition

Minor W. Bruce was the Alaska correspondent for the Omaha Bee, or so the paper referred to him in its pages. In a time when many journalists were well versed in exaggeration, Bruce was borderline dishonest in his reporting.

“He was an enterprising journalist of the irresponsible kind and made an excellent second to Willoughby,” Rickard wrote.

The two were co-conspirators of sorts, and according to Willoughby’s obituary, it was Bruce who gave Willoughby the nickname of “Professor.” As buzz spread of Willoughby’s Silent City and the summer solstice of 1889 was approaching, the two of them hatched a plan.

They, along with a few others, went on an expedition to Muir Glacier in order to get another photo of the floating city and have other witnesses confirm the site. They set sail for the glacier, going around the south end of Douglas Island, up the Chatham Strait and up to Glacier Bay.

Nobody in Juneau heard of them for a few weeks, Rickard wrote, until people aboard a steamer called the George W. Elder came into port with an update.

A man from Willoughby’s expedition had come aboard in Glacier Bay, they said, telling a harrowing tale of Bruce’s disappearance and possible death. Bruce had walked into the fog that hung above the glacier, the man said, and when members of the expedition went out a while later to find Bruce, all they found was his camera.

Near the camera, the man said, was a large crevasse. They feared the worst, and the man asked the crew of the George W. Elder for ropes to help search for Bruce. They gave him some, and the man headed back out to the treacherous glacier. This is all according to Rickard’s account.

Almost a month later, Willoughby and his companions arrived back in Juneau, with good news. Bruce had been found, or as the New York Times headline read, “Correspondent Bruce Not Dead.” According to the brief Times report, Bruce had been lost on the glacier for three days before Natives found him and returned him to his party.

During the trip, Bruce claimed, he had caught a glimpse of the Silent City. Of course, he had left his camera back by the crevasse, so there was no photographic proof. This apparent brush with death stoked excitement even more about the floating mirage, and sales of the photo spiked.

The source of the farce

It all began on Vancouver Island in 1887, Rickard wrote, when Willoughby happened upon a young tourist from Bristol, England on the docks there. The tourist was selling a box of photographic negatives for $10, and Willoughby purchased them.

Among the negatives was an over-exposed picture of Bristol, Rickard wrote. From here, Willoughby’s imagination took off. Before he knew it, the hoax had spread all around the country, with newspapers picking it up and publicizing the miraculous mirage.

Most people didn’t notice — either by ignorance or because they wanted to believe — that the elm trees present in Willoughby’s photograph were bare, without leaves in the middle of the summer.

“A more transparent fraud could hardly be devised,” Jordan wrote, “but its very imbecility assures its success.”

Stanford University Professor William H. Hudson, who had lived in Bristol for a time, is credited with figuring out the farce. Hudson saw the picture and immediately recognized it, Jordan wrote in “Popular Science,” and said the photo must have been about 20 years old. The building that had the scaffolding around it, he said, had long been repaired.

Is it possible?

Multiple glacier researchers spoke to the Empire about the Silent City and if there was even a possibility that this kind of mirage could occur.

Steve Warren, an emeritus professor at the University of Washington Department of Atmospheric Sciences, said mirages occur when there are large differences in temperature near the surface of a body of water or land.

Warren said he had never heard of Willoughby’s Silent City, and said seeing mirages on Alaska glaciers is generally uncommon.

“I cannot recall ever seeing a mirage on an Alaskan glacier,” Warren said via email. “This may be because of the nearby topography; mirages are usually seen only in the direction of a distant horizon. Also, mirages are more common in winter, so my summers on the Juneau Icefield were not a good time to look for mirages.”

University of Alaska Fairbanks physics professor Martin Truffer said he’s seen mirages on glaciers before, but nothing quite as dramatic as a discernible shape. Seth Campbell, the director of academics and research for the Juneau Icefield Research Program, said the conditions are much more ideal in Antarctica for mirages.

“This could certainly cause a mirage, and ‘misinterpreted features’ perhaps,” Campbell wrote in an email, “though a mirage of an entire city, quite unlikely.”

Still beloved

It’s not clear whether Willoughby ever admitted to the hoax.

Willoughby certainly didn’t stop messing with strangers after he was found out. He went down to Seattle in 1895, according to his obituary, and was hardly off the boat before he started spinning another yarn. After living in Alaska all those years, he claimed, he had never seen a railroad train. Reporters ran with that one, the obituary reads.

He later told a woman that his isolation in Alaska was so complete that he never even heard of the Civil War until it was over.

Willoughby died in May 1902 in Seattle, according to his obituary. Word of his exploits and his tricks continued to circulate, especially in Juneau, where “Uncle Dick” was beloved.

In 1913, a boardwalk was built on pilings over the high tide line to connect the Indian Village to downtown Juneau, according to the City and Borough of Juneau’s Willoughby District Plan. The boardwalk eventually became a road, and it came to be known as Willoughby Avenue.

Today, the area surrounding the street has been dubbed the Willoughby District, which houses many of Juneau’s cultural hubs. The Father Andrew P. Kashevaroff State Library, Archives and Museum, as well as the Andrew Hope Building, Juneau Arts and Culture Center and Centennial Hall all reside in the Willoughby District.

Stories from the “Professor” still live on, in the pages of history and even the occasional newspaper article.

• Contact reporter Alex McCarthy at 523-2271 or amccarthy@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @akmccarthy.