Vera Starbard found the connection between art and healing accidentally.

If she grew up in an Alaska that was never colonized, she believes she would have learned that link much earlier in her life.

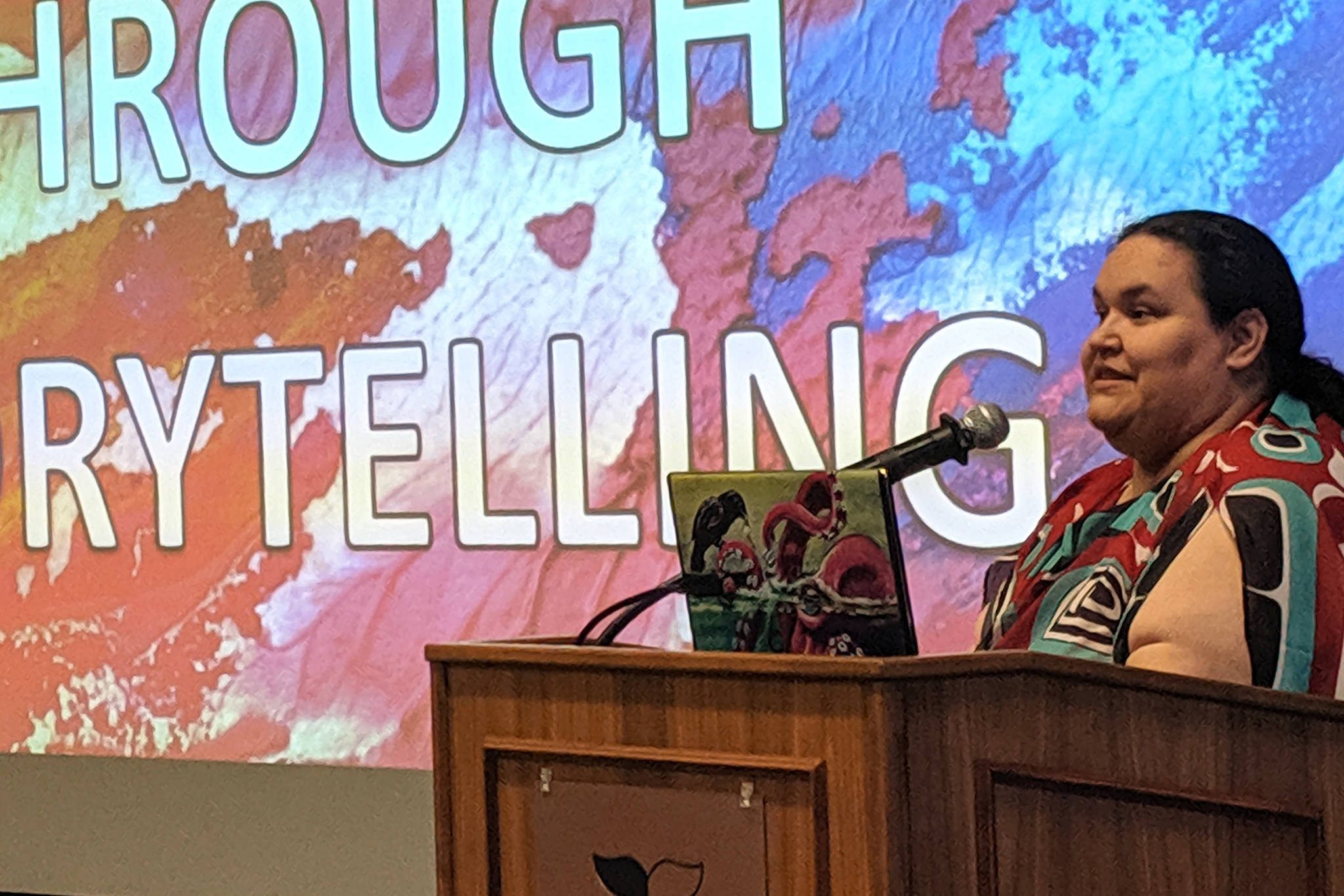

“I never was told, ‘Go write, go create art to heal,’” Starbard said Friday during a lecture at University of Alaska Southeast’s Egan Library. “It was something I discovered myself. If we had the same traditions that we always had, and they were not taken from us, I absolutely would have been taught those things.”

Starbard is Perseverance Theatre’s playwright-in-residence, and she’s behind the new play “Devilfish.” Her lecture, titled “(Still) Healing Through Art,” focused on both the measurable and harder to pin down ways art helps the healing process. It also served as a sort of preamble to and pilot for workshops of the same title Starbard plans to take around Southeast Alaska.

“You’re my guinea pigs,” Starbard said to her audience.

“(Still) Healing Through Art” is intended to be a follow-up to “Healing Through Art” workshops Starbard led after the premiere of her play “Our Voices Will Be Heard.” Starbard described the production as a “19th-century version” of her autobiography based on what happened when Starbard’s mother discovered Starbard had been sexually abused by her uncle.

[Library intern masterminds a night of song and dance to celebrate people of color]

“That definitely sort of launched me further into that world of healing,” Starbard said. “A direct result of that was the workshop ‘Healing Through Storytelling.’ I did that because we knew there was going to be some issues coming up for people with the play.”

That earlier workshop introduced participants to different forms of art that could potentially serve as a medium for communicating emotions. Starbard said her parents discovered her abuse after seeing her drawings as a child.

“Art is a way for people who struggle to know what to say to say something,” Starbard said.

She said the goal of her next workshop will be to examine ways whole communities can heal.

“It’s going to be a community answer, it’s going to be a community-driven answer,” Starbard said. “What should we do? Two, how can we start doing it? And three, how can we make sure others know about it?”

Starbard used Tlingit tradition as an example of what communal healing can look like and emphasized the role creative efforts played in those traditions.

“What we did was very communal,” Starbard said. “You grieved communally. You grieved communally. You healed communally. That was never something you were going to face alone ever. That’s so strikingly different from what I understand modern United States’ grieving to be.”

Starbard gave an abridged description of what that communal process was like.

“As a Raven, an Eagle person, like my husband, or relatives that are Eagle would take care of me, and we call that ‘lifting you up,’” Starbard said. “That is their responsibility to do.”

Eventually, sometimes years later, a memorial party would serve as an opportunity for the griever to repay those acts of kindness, Starbard said.

“You would spend all that time creating things,” Starbard said. “You would gather and spend many days receiving these gifts, being fed, being paid back for the days they lifted you up. It was one of the most beautiful traditions we had.”

Starbard used the past tense because following the U.S. purchase of Alaska, “potlatches” were illegalized.

That coincided with small pox and flu epidemics and the advent of boarding schools, Starbard said. Beginning in the 19th century and lasting well into the 20th century, the U.S. government forced indigenous children to attend boarding schools in an effort to force assimilation.

“What we did not have at that exact moment in time was a process of grief,” Starbard said. “A lot of those traditions were lost because the people couldn’t pass it on.”

[Have you seen what the numbers say about Juneau’s air quality?]

However, Starbard gladly noted Alaska Native cultures were not entirely extinguished, and there are many signs of a resurgence.

“We now do memorial parties,” she said. “We’ve done those things since I was a kid, but we’re doing more of them. We’re really relearning that process of grief, even though it’s hard. It’s very hard to heal when you might live all over the world, but we’re doing it.”

Starbard said still more is needed, and it may take thinking outside the box of American Exceptionalism and individuality.

“How do you as a community say, ‘This is how we’re going to heal together, this is what we’re going to do, this is who’s responsible for taking care of the people who are grieving and what is my responsibility to that group, and who’s going to take care of me?’” Starbard asked. “That’s a huge step that we have to take that we really don’t have right now. In a lot of ways, those are our next steps.”

• Contact reporter Ben Hohenstatt at (907)523-2243 or bhohenstatt@juneauempire.com. Follow him on Twitter at @BenHohenstatt.