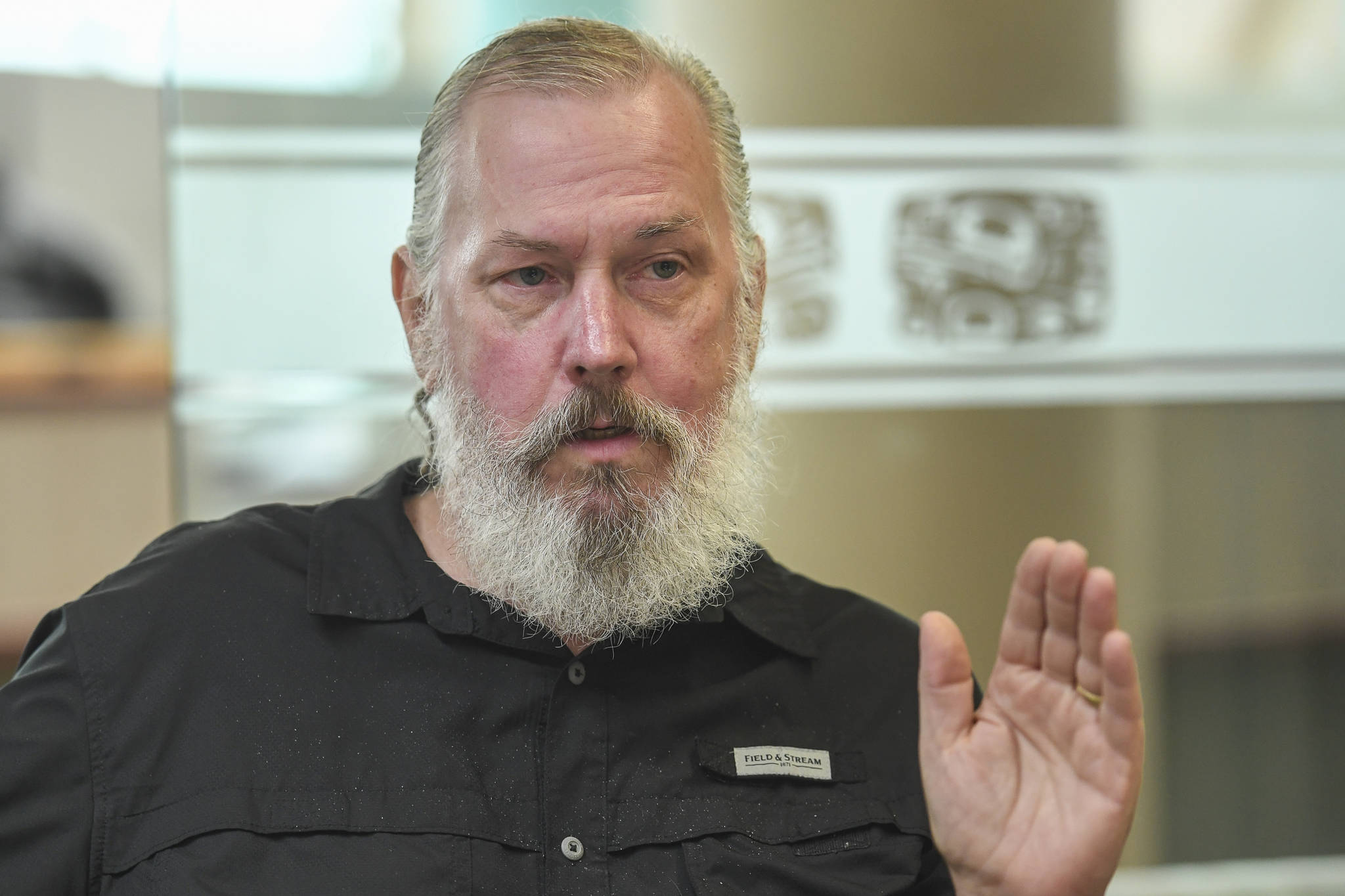

James Helfinstine retired Wednesday from government service, after working for the federal government in one capacity or another for more than 40 years, almost entirely in Alaska.

Beginning his time in federal service as a Marine, Helfinstine spent most of those 40 years as a civilian administrator with the United State Coast Guard’s 17th District Bridge Administration program, located in Juneau.

During his time with this program, he’s overseen permitting for a huge number of projects, including the Ketchikan/Gravina Access — better known as the “Bridge to Nowhere” — and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, whose river crossings count as bridges. He’s also worked on proposed bridges such as the Knik Arm Crossing and the Juneau Access project, both of which are in limbo due to their proposed cost and lack of perceived need.

“If there’s a road, there’s going to be a bridge, because there’s a lot of waterways,” Helfinstine said.

The job of permitting bridges for construction has fallen to the Coast Guard since 1967, with the remit to keep the navigable waterways clear for boating traffic. Rule of thumb, Helfinstine said, is that any body of water that can support a boat carrying a flat ton of cargo is navigable.

“I’m really proud of working for the Coast Guard, because they’re honest brokers,” Helfinstine said.

This has led to different requirements for different bridges. Bridges crossing smaller rivers don’t need to be 200 feet tall. But a bridge crossing a major shipping channel in the Inside Passage would need to accommodate the massive cruise liners and commercial shipping that ply those waters.

“The ships that used to come had 200 passengers,” Helfinstine said. “Now, they have 7,000.”

The explosion of tourism in Alaska has led to larger and larger numbers of passengers in larger and larger ships to the region. The maximum height of the cruise ships, defined by the Panama Canal’s constraints, is roughly 170 feet. This would have been the height the Ketchikan bridge would have needed to clear as originally proposed. Building tall bridges is more expensive than short bridges, Helfinstine said, and the Ketchikan bridge would have to be very tall indeed.

“In order to get it high enough, it was going to cost an awful lot of money,” Helfinstine said.

The project, which would have cost hundreds of millions of dollars, got canceled because it got too political, Helfinstine said. The Bridge to Nowhere would have consisted of two spans, one of which would have been more than 200 feet tall, nearly as tall as the Golden Gate Bridge, according to Helfinstine.

Helfinstine has also been involved in all proposed pipeline projects in Alaska, including seven seperate proposals to build a liquid natural gas pipeline from the vast LNG reserves in the Arctic to the south where it could be more conveniently shipped out. For the purposes of permitting, pipelines are in the same category as bridges: permanent structures that could hamper marine navigation. The pipeline has more than 48 crossings along its length, Helfinstine said.

“I’ve been up and down the pipeline 14 times,” said Helfinstine.

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline is more than 800 miles long from end to end, through some exceptionally desolate country. Helfinstine also became a member of the Joint Pipeline Office, created to regulate and monitor the pipeline following accidents along the line. During the course of this and other work, Helfinstine said, he flew more than a million miles in Alaska, far enough to reach the moon and return twice.

From the Marines to Alaska, working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, to the Coast Guard, Helfinstine has been all over the state. He’s surveyed, permitted and walked the grounds from project to project, laying the threads that tie the state together.

“It’s been a long career,” said Helfinstine.

• Contact reporter Michael S. Lockett at 523-2271 or mlockett@juneauempire.com.