Just about everyone agrees ranked choice voting worked as intended as a moderating influence when used for the first time in Alaska’s elections this year, which is why there’s even more division about either establishing it as role model on a much larger scale or banishing it from existence.

Another consensus is active debate will continue almost without pause in Alaska since a petition to repeal ranked choice voting is already circulating and state lawmakers agree proposals to do the same will be on the agenda during the coming legislative session. Part of the discussion will involve related aspects such open-party primaries that allow up to four candidates to be ranked during the general election and voter turnout in the November election being the lowest in state history by a significant margin.

“Whatever happens I’m sure there will be a bill in the Legislature, and I look forward to a very spirited investigation about how ranked choice voting works,” said Senate President Gary Stevens, R-Kodiak, during a news conference Friday announcing a 17-member bipartisan Senate majority he will preside over next session. Members not in the coalition have stated they will pursue such legislation.

“Most people I’ve talked to are happy with how ranked choice voting worked,” he said.

Plenty of activity is expected outside the state as well, since Nevada, Washington, Vermont, Colorado and other states are implementing or considering ranked choice voting to some degree (while others, such as Florida are enacting laws banning it). For supporters, it’s a way to counter what they see as increasing divisiveness and extremism by candidates considered viable.

“As our states have gotten and — especially our congressional districts have gotten more polarized — fewer number of people are picking the winners because winners are chosen in primaries,” Jessica Taylor, an editor at the Cook Political Report, said in an interview after the election with National Public Radio. “I’m asked a lot when I’m speaking and traveling and talking to groups about what can we do about the partisanship in our politics, and I point to these reforms in Maine and Alaska and in Nevada, if this passes (there) a second time, as one way that sort of could decrease the political fever.”

A key question without a definitive answer is how much difference ranked choice voting made in terms of who won the races in Alaska’s general election.

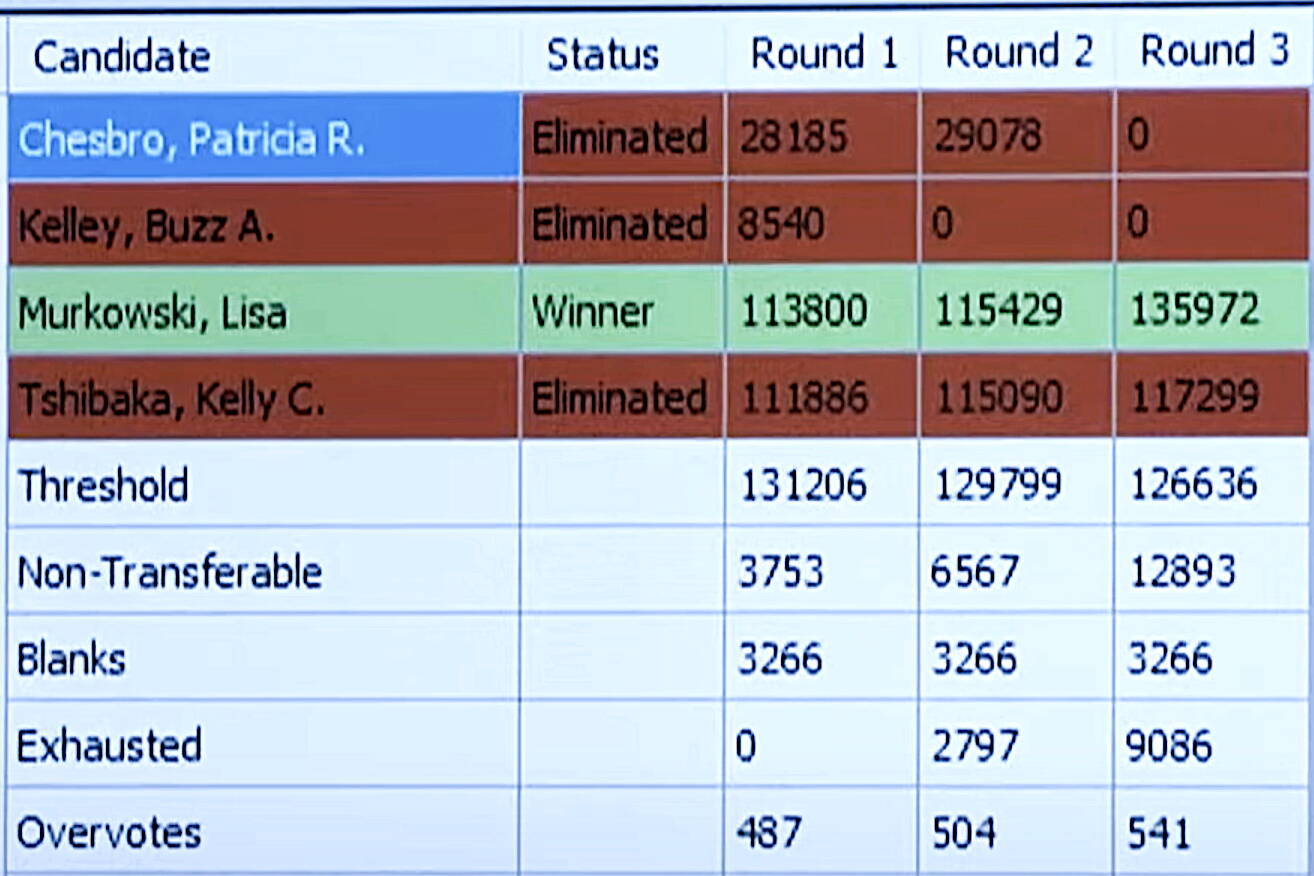

Proponents of the ranked choice in particular note the incumbent “moderates” in Alaska’s two congressional races — U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski and U.S. Rep. Mary Peltola — got more first-choice votes than their opponents and thus would have prevailed regardless of the counting method.

But others analyzing the results argue the question is more complex because of additional factors, notably the also-new open primary where the top four finishers advance to the general election regardless of party. Without that primary, the argument goes, the special U.S. House race held months before November’s general election might not have attracted anywhere near 48 candidates and thus Nick Begich III, who had stronger support from the state’s Republican Party apparatus than former Gov. Sarah Palin even though she got more votes, could have prevailed in the special election and a closed-party primary, and then defeated Peltola in a two-candidate general election.

Similarly, U.S. Senate challenger Kelly Tshibaka was strongly favored by the Alaska Republican Party, which censured Murkowski earlier this year for supporting the impeachment of former President Donald Trump. While Tshibaka had fewer votes than Murkowski in both the primary — with crossover votes from Democrats a key factor — and first-choice general election count, a closed primary might have produced a different outcome.

“Ranked choice voting also opened the primaries and the primaries are the choke point for both parties,” said Andrew Halcro, a former state Republican lawmaker and current political analyst. “In a closed primary Tshibaka beats Murkowski.”

Palin, a week before the ranked choice results were announced, made headlines by being the first person to sign the petition seeking an initiative to repeal the counting method by the 2024 general election.

“Ranked choice voting is the weirdest, most convoluted and most complicated voter suppression tool that Alaskans could have come up with,” she said during the signing event in Anchorage. “And the point is, we didn’t come up with this. We were sold a bill of goods.”

But if ranked choice voting altered the outcomes, post-election surveys suggest Alaskans — who approved its implementation in 2020 — widely supported the results.

An exit poll shows 92% of respondents said they were instructed sufficiently about how ranked choice voting works and about 90% percent said the process was simple, Sen.-elect Cathy Giessel, R-Anchorage, said during Friday’s press conference announcing the new coalition in which she’ll the majority leader.

“Sixty percent felt the races were more competitive,” she said. “We certainly saw a diversity of people winning the races. It wasn’t one party or the other.”

Two state House races in particular were won by Republicans on second- and third-choice ballots after Democrats seemingly were in position to win them when the first-choice ballots were tallied, which in turn means a presumed bipartisan majority in that chamber has been cast into uncertainty unlikely to be resolved by the start of the session in January. While the current results have Republicans winning 21 of the 40 seats, one race separated by four votes is headed to an automatic recount and then at least some GOP members will weigh if they want to align with the most partisan members of their party or enter an agreement with Democrats.

But while Giessel cites the high comprehension and satisfaction of residents participating in the exit surveys, a critical number is the voter turnout of about 44%, which is well below the next-lowest turnout of 49.84% in 2018, with rural Alaska in particular seeing declines.

“We seriously need to look into that and find out why,” she said. “It’s possible people in rural areas looked at people on ballot and said ’I like all of these’ and just didn’t go to the voting booth.”

It is possible attacks by opponents of ranked choice voting questioning its integrity and alleged complexity deterred some people from voting, said former Juneau Mayor Bruce Botelho, who co-chaired the group Alaskans for Better Elections that advocated for ranked choice voting.

“Early on there was confusion about how ranked choice voting worked,” he said. “There was a lot of noise in certain circles about ranked choice voting, and I think that may have had some impact on people’s willingness to turn out.”

On the other hand, while the number of candidates running in the statewide races was much higher than normal due to the open primaries, that also meant “giving the Alaska electorate a wide range of choices and individual views about our government and our society,” Botelho said.

“We saw a higher number of candidates in higher races than we had in years,” he said. “The interesting thing that happened as well is there were a lot of races where multiple candidates from the same parties advanced.”

A surprise is the number of people who did not rank any candidates beyond their first choice, Botelho said. That proved decisive in the special U.S. House race in particular, where a high percentage of Republicans favoring either Begich or Palin left their subsequent choices blank, allowing Peltola with about 40% of the first-choice vote to achieve an eventual majority.

“I think if one looks at many of the races here that was decisive, but I think it also illustrates one of the great aspects of ranked choice voting,” Botelho said. “You have the opportunity to rank candidates and you also have the opportunity to vote for the candidate of your first choice without being compelled.”

Despite high-publicity denouncements by ranked choice opponents about the fairness and integrity of the process, none showed up in-person to observe either of the two official tallies at the state Division of Elections office. Only a few observers generally favorable of the process and members of the media watched the general election counts as they were broadcast on live TV, and they were no immediate calls by opponents for challenges to the results afterward.

The results are scheduled to be certified Tuesday, after which losing candidates have up to five days to request a recount and 10 days to file an official challenge. Giessel said the automatic recount in the four-vote-margin race will offer “a chance for Alaskans to remind themselves we have paper ballots and can do hand recount.”

“I think that will help provide that comfort voters need, but it all has to play out yet,” she said.

Such questions about Alaska’s results in terms of the integrity of the process, turnout, the connection to open primaries and plenty of other data crunching are likely to be tackled by researchers and policymakers nationwide, since more than 15 states have either implemented ranked choice voting on at least a municipal level or are considering doing so.

“Political scientists will be busy for quite a while with this one,” Giessel said.

• Contact Mark Sabbatini at mark.sabbatini@juneauempire.com