MBAR TOUBAB, Senegal — It seems like Mission Impossible: Stop the Sahara Desert from spreading farther south, its incursion into arable land fueled by climate change and overgrazing.

But tree by tree, a Great Green Wall is being planted across a belt of Africa to fight back, though the success of the Herculean effort depends in large part on about a dozen countries making a concerted effort and on funding.

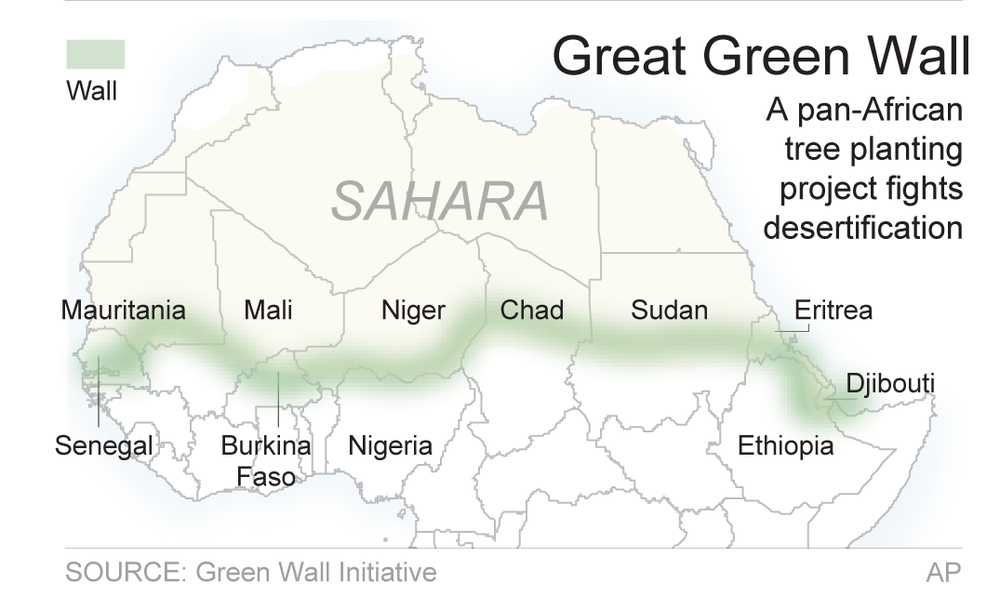

Under plans launched in 2007, the Great Green Wall will be an arc of trees and plants running 4,350 miles across Africa — from Senegal along the Atlantic all the way to Djibouti on the Gulf of Aden.

The 9-mile wide wall is a part of a wider initiative meant to help reduce seasonal winds packed with sand and dust, slow land degradation and the encroaching desert, and to improve the health and lives of those living nearby.

So far in Senegal, the country furthest along in the project, 99,000 acres has been planted along a line of 93 miles, that will eventually extend to 340 miles covering about 1,976,800 acres, according to Senegal’s national agency for the project.

In Senegalese villages like Mbar Toubab, market gardening is now possible, allowing women like 38-year-old Aissata Ka to make more money as agriculture and economic opportunities blossom where acacia trees now grow.

“Agriculture is easier for us,” said Ka, who lives in Mbar Toubab in Senegal’s north. “With livestock, the herd can die at any moment, and you are then condemned to live as a nomad. Here, with agriculture, we don’t need to move.”

Ousseynou Toure, an expert with the Program of Local Development in Senegal that advises the government, named another benefit.

“It has also helped the health of children by reducing the dust and winds,” he said

Senegal’s successes have come from not only working with communities, but with researchers to be sure the trees that will thrive most are planted.

Land degradation advances quickly with changes in the climate, and must be stopped to preserve the ecosystem and restore the natural order of things, Toure noted.

He stressed that the project must continue to be linked with social services so that any gains can be maintained.

Each of the 11 countries that the wall is supposed to pass through decides what its needs are for the initiative and how it maintains each section, he said. So if one country’s policies shift and they don’t maintain their part of the swath of trees, it could impact neighboring countries, Toure said.

The project, launched by African leaders, is being strengthened through intergovernmental meetings and agreements over the years with support from the United Nations and other organizations.

Mohamed Adow, senior climate change adviser for the international development agency Christian Aid, says it’s important that such regeneration projects respect the rights of locals and are supported by communities.

“Selecting the right species (of trees and plants) and developing the right community-based forest management systems are vital to avoid simply ending up with a line of forest plantations that are resented by local people and subject to illegal logging and wood collection,” he told The Associated Press in an email.

As the climate conference in Paris wraps up, Toure said that he hopes the project remains a priority.

African leaders at the Paris talks described the Sahara Desert encroaching on farmland, along with forests disappearing from Congo to Madagascar and rising sea levels swallowing homes in West African river deltas. They said the fight against desertification is a priority.

French President Francois Hollande has said France will invest billions of euros in coming years for renewable energy in Africa, to increase Africans’ access to electricity and for adaptation to climate change. France’s development aid will also focus on the Great Green Wall, the protection of Lake Chad and the Niger River, among other projects, Hollande said.

Conflicts in some countries like Mali, which has Islamic extremist fighters, could delay progress in the planting of the tress, noted Gilles Boetsch of the French National Center of Scientific Research.

Still, Papa Sarr, the technical director of Senegal’s National Agency of the Great Green Wall, said that while the project is still young, the level of revegetation and the subsequent financial benefits for locals are “cause for optimism.”

___

Petesch reported from Dakar, Senegal.