The Marine Exchange of Alaska (MXAK) is a relatively unassuming building by Aurora Harbor. But its footstep well outweighs its modest size.

“We’re taking the search out of search and rescue and getting straight to the rescue,” said Matt York, former Coast Guardsman and network operations supervisor for MXAK.

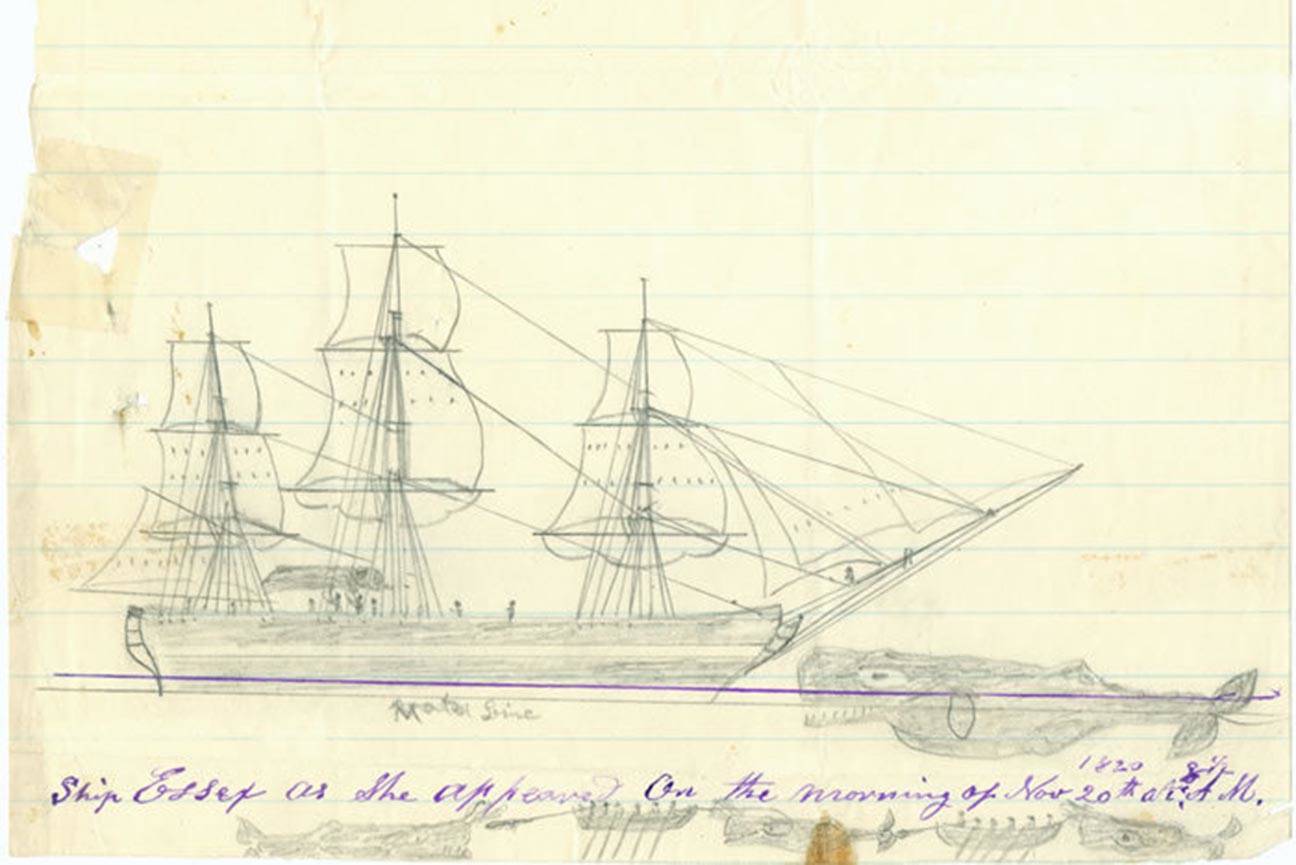

During a presentation at the Juneau Public Library on Thursday night, York talked about some of the advances in technology that make search and rescue (SAR) a more precise and efficient process than it used to be, using the wreck of the Essex to illustrate what SAR used to entail.

Nathaniel Philbrick’s book “In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex” describes the sinking of the whaleship Essex, homeported in Nantucket, Massachusetts. Sunk in the open Pacific in 1820 when it was struck abeam by an enraged sperm whale, only eight crew survived out of 20 as the survivors floated for nearly 100 days across the open Pacific.

York highlighted a number of technologies which allow for much more rapid and reliable rescues. Rescue beacons that ping satellites when their ship goes down are much more common now. The Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Rescue System (AMVER), a Coast Guard program where vessels stay in communication with the Coast Guard, allows those vessels to be rapidly alerted in case of an at-sea emergency, positioning them so they can support rescue operations, York said.

An AMVER vessel, the MV Williamsburgh, assisted in the rescue efforts of the MS Prisendam, a cruise ship that burned and sank in the Gulf of Alaska in 1980. The program has achieved wide popularity, York said, especially out in the North Pacific where organizations capable of providing SAR support can be far away.

The most modern technology available to ship crews is the Automatic Information System (AIS), which integrates location and radar data with the ship’s electronic chart system to give captains an accurate picture of what’s around them, York said. Ships of above a certain size, number of passengers, or fulfilling certain roles are required to carry an AIS system. The system also pings back to the MXAK operations center, so they can see the speed and location of every ship in the Pacific.

“That’s a big portion of funding through the Coast Guard,” York said. “The other portion is through the industry.”

[Coast Guard training with Marines and Navy in Alaska exercise]

MXAK maintains a network of 139 AIS stations on land to help fix the position of vessels with AIS systems at sea, York said. Many of those stations are also able to provide real time weather data. The AIS stations, constructed all over the coasts of Alaska, often in remote places, have to be powered and connected to the internet by a number of innovative means, York said.

“I think there’s about 21 internet providers in Alaska and we pay all of them,” York said.

The wreck of the Exxon Valdez in Alaska in 1989 caused a series of rapid reevaluations in maritime safety, codified in the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, York said. Part of the response was to mandate superior navigational and safety aids in ships. With the AIS, MXAK is able to monitor every ship in Alaska’s water, and flag ones that appear to be in trouble. There are more than 2,000 vessels operating regularly around Alaska on average, York said, with more in the summer and fewer in the winter.

“We monitor what’s called these vessels of concern,” York said. “If it’s under 3 knots or if they transmit ‘not in command,’ we contact the vessel.”

York said the MXAK gets roughly five vessels of concern a week. Some are simply slowing down due to inclement weather, but some are genuinely in distress. If that’s the case, MXAK already knows their location within 1.5 meters (about 4.5 feet) through their AIS, and can get the ball rolling to solve the problem as fast as possible.

[Two men flown to safety from Lemon Creek glacier]

“If they say, “Hey, I’m in trouble,” we alert the Coast Guard,” York said. “It speeds up the response to a vessel casualty.”

York said that of the most recent vessels assisted, one was a car carrier that lost propulsion. An electrician had to be located and a replacement part located, but the vessel was never in danger, and in fact, never made the papers.

Not every vessel is so lucky, however. In 2004, the freighter MV Selendang Ayu lost propulsion off Unalaska Island sailing the great circle route west. Suffering an engine casualty, and trying to hold off calling for help until the situation was beyond salvaging, the ship drifted inshore, propelled by heavy winds. York said that most of the crew was rescued, though one Coast Guard helicopter was destroyed by a wave, killing 6 of the freighter’s crew. The ship grounded and snapped her spine, breaking the ship in two.

Since then, York said, Alaska has been constantly improving in keeping its ships and sailors safe. The sea can be an implacable foe, but better technology means more of those who draw her ire will live to return home.

• Contact reporter Michael S. Lockett at 757.621.1197 or mlockett@juneauempire.com.