Alaska was the second state to adopt ranked choice voting in federal and statewide elections, but it may be the first to abandon it.

A citizen’s initiative ballot measure that would repeal the state’s open primary and ranked choice voting system made it to the November ballot after legal challenges. As a result, Alaskans will be asked in Ballot Measure 2 to decide if they would like to repeal or keep the state’s open primary and top-four ranked choice voting system.

If the repeal is successful, Alaska will revert to primaries that are controlled by the political parties and general elections where voters pick only one candidate.

The repeal effort centers its argument around the ranked choice aspect of the state’s voting system, while proponents of the system have dug in to fight for the open primary aspect.

The 2020 ballot measure to institute ranked choice voting succeeded with 51% of the vote. But efforts to roll it back ramped up after the system’s debut in the 2022 election.

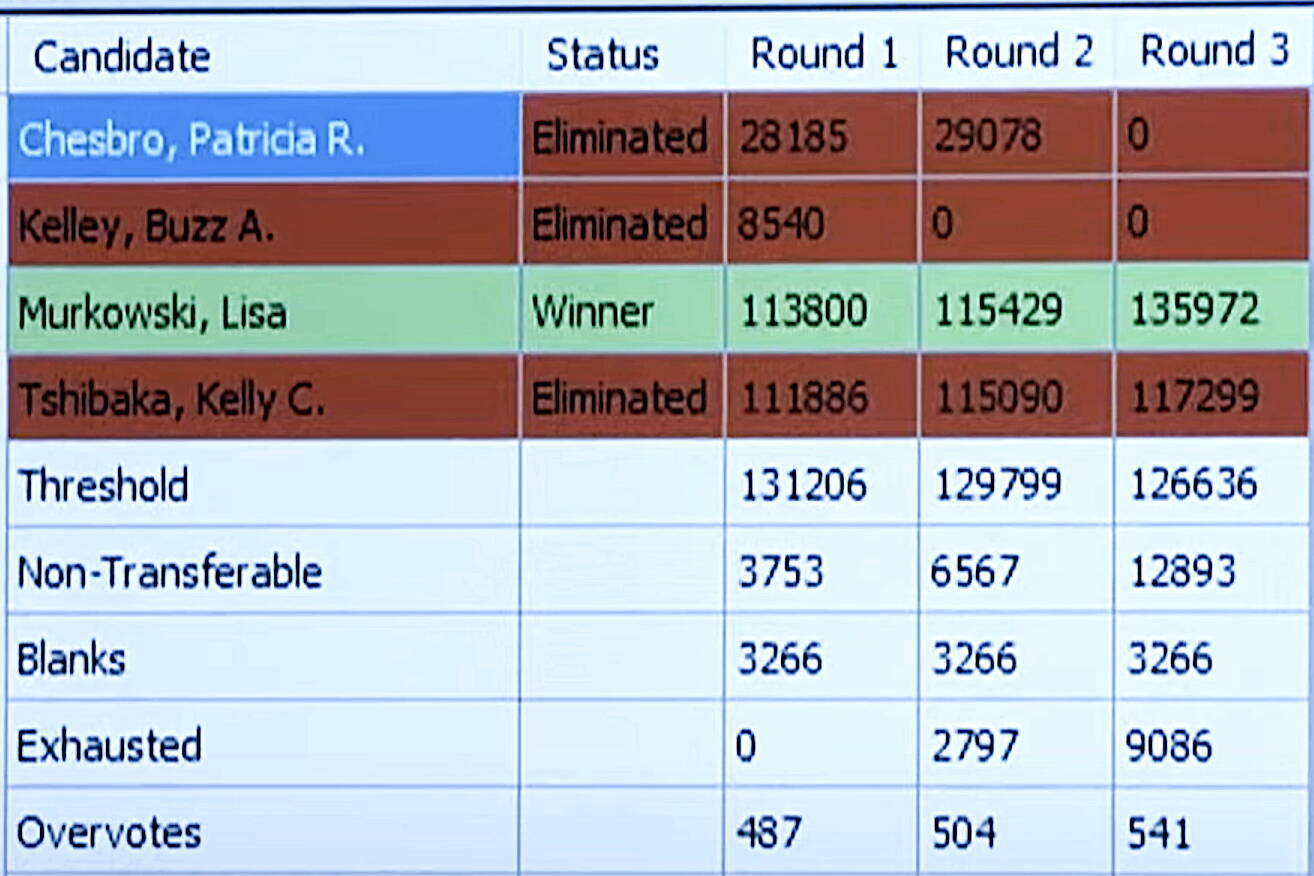

The 2022 results showed the range of possibilities in statewide elections under the election system: conservative Republican Mike Dunleavy was reelected as governor, moderate Republican Lisa Murkowski was reelected as a U.S. senator, and Democrat Mary Peltola was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

How Alaska’s open primary and ranked choice elections work

Alaska’s open primary means that every voter is eligible to vote for any candidate, regardless of political affiliation, in the primary election. The top-four voter getters move on to the general election.

The general election is decided by ranked choice voting, which means that voters get to rank the four candidates in order of preference. If one candidate gets more than 50% of the votes, they win. If the votes are more evenly split, the candidate with the least first-preference votes is eliminated. Voters who selected the eliminated candidate as their first choice now have their second choice counted, so their vote still counts even if their preferred candidate is eliminated. If the vote redistribution results in a majority, that decides the election. If not, the third place candidate is eliminated.

Is it partisan?

Phillip Izon II, the man behind the citizen’s initiative effort to repeal the open primary and ranked choice voting, said the effort is about finding the fairest possible voting system, not about its partisan implications.

“The main objective wasn’t because I was a party member, or I was associated with the Republican Party, or anything like that,” he said. “It was primarily because I believe that there was a large percentage of the people, not just in Alaska, but anywhere that ranked choice voting is being implemented, that don’t understand ranked choice voting, and it complicates their voting so much to the point where they just stop voting.”

He pointed to a low general election turnout in 2022 — the lowest in decades.

Prominent Republicans have backed Ballot Measure 2, however. Former Gov. Sara Palin, still smarting from her loss for the state’s sole House seat, was the first to sign the repeal effort’s petition, the Anchorage Daily News reported at the time. And some Republicans pledged to withdraw from their races in this election cycle if they were not among the top vote getters in the primary, in an effort to circumvent the ranked choice system.

But the repeal opposition campaign, No on 2, is chaired by former state Sen. Lesil McGuire, an Anchorage Republican, and has collected millions in donations from national nonpartisan organizations.

Open primaries and ranked choice has benefited Republican and Democrat candidates alike. Notably, Democrat Mary Peltola was elected to the state’s only House seat in Congress after it was filled by Republican Don Young for nearly half a century. Republican Reps. Julie Coulombe and Tom McKay, who were both members of the House’s Republican majority caucus and who both support the repeal, were elected after trailing among voters’ first preferences under the ranked choice system.

What does it cost

State elections officials estimate it would cost $2.5 million to repeal ranked choice voting. That comes after the price tag to institute them, which was $3.5 million in a June estimate from state officials.

But Juli Lucky, campaign manager for No on 2, said there are other costs to an Alaska without open primaries and ranked choice voting, that come in the form of political gridlock. She argues that before open primaries and ranked choice voting, the state’s Legislature was more polarized, and that was expensive.

“The Legislature was not getting organized on time. There was a lot of partisan fighting. We were seeing delays of about 30 days where the Legislature wasn’t actually getting to work, and then we saw a lot of special sessions where there was a lot of arguments and not a lot of solving problems,” she said.

The Legislature called four special sessions in 2021, the year before open primaries and ranked choice voting, costing nearly $2 million.

Open primaries

For the last two decades, Alaska’s primary has been partially closed. The Republican Party limited its primary to registered Republicans and those without a party, while excluding Democrats and third-party voters. The other parties, including the Democratic, Libertarian and Alaskan Independence parties, have shared a primary ballot.

In 2022, with the advent of open primaries, there was only one ballot and all the candidates in each race were on it. Advocates of the open primary say that it benefits the majority of Alaskans because most are not registered with a major political party and do not vote a “straight ticket” — they vote for candidates from multiple political parties in different races. For example, a voter might choose a Republican to represent them as state senator, but a Democrat to represent them in the state House.

Lucky said that ending the open primary would give more power to political parties than to individual Alaskans because parties can choose to close their primaries.

“Right now, we have a system where every Alaskan can vote for any candidate at every election, regardless of the party,” Lucky said. “What’s at stake is taking power away from voters to choose the candidate they like at every election. And I think that’s incredibly important because in the past what we’ve seen is that a lot of races get decided in that lower-turnout primary, which in the recent past has been a closed primary, where voters did not have the ability to look at all the candidates and choose from all the candidates.”

But what looks like a benefit to Lucky, is considered a flaw by those who would like to see the end of the open primary.

Michael Tavoliero, a contributor to conservative Alaska news site Must Read Alaska, wrote in an August post that open primaries and ranked choice voting “blur the lines between political parties, allowing non-Republicans to influence the outcome of Republican primaries and erode both party integrity and conservative values.”

So the multiplicity of choice that open primary proponents value is, in his view, a threat to party ideology.

“In a closed primary, only registered Republicans would have a say in choosing their candidate, ensuring that the nominee aligns closely with the party’s ideology,” he wrote. “Open primaries, on the other hand, can lead to the nomination of candidates who appeal to a broader, less ideologically consistent electorate, potentially weakening the party’s stance on key issues like small government and personal freedom.”

Scott Kendall, an Alaska attorney who helped write the citizen’s initiative that led to open primaries and opposes a repeal, countered that diluting the influence of the parties may be more consistent with representing the will of the majority of Alaska’s electorate that are not affiliated with either major political party.

Of a repeal, he said: “We would be going back to a system where over 80% of the races are decided in the primary by a much more partisan, much smaller group of voters. And I think that’s a huge loss.”

Though Izon’s focus is ranked choice voting, he said the open primary is worth repealing because it is susceptible to manipulation.

“Anybody can finance a candidate to get on the ballot and get into the top four, and then tell them to drop out,” he said, adding that the idea should scare people from any political party. He pointed to the case of Eric Hafner, the imprisoned out-of-state Democrat who is on the U.S. House ballot after a legal challenge failed. “There’s a sizable chunk of the population that don’t even know Eric Hafner is in prison,” Izon said.

He said there are multiple examples of spoiler candidates in this year’s election, so he would rather political parties vet candidates than deal with that.

“Would you rather vote a straight ticket or have a criminal on your ballot in a general [election]?” he asked. “Personally, I would rather vote a straight ticket.”

Ranked choice voting

The main argument of many opponents of ranked choice voting is that ranking candidates is too confusing for voters. Izon said he thinks that confusion is behind a low turnout in Alaska’s 2022 general election. He said it was his grandfather’s bafflement when confronted with a ranked choice ballot that compelled him to begin the recall in the first place.

Lucky countered there were multiple factors that made voting confusing in 2022 that had nothing to do with ranking candidates. She pointed to a redistricting effort that shook up the Legislature.

“Everybody except for one senator had enough change in their district that their seats were up for election, or they were on a schedule where their seats were up for election,” she said.

Additionally, she said, there was a special election to fill Don Young’s congressional seat after his death, closely followed by that year’s primary election.

Nevertheless, she said, 99.8% of ballots in the 2022 general election were filled out properly and more than 70% of voters ranked candidates. She said those results show that voters do understand the election system.

Izon reflected that in fighting one confusing change, he may be precipitating another. But he said he is driven to find the most fair voting system.

“Every time we make a change, we’re hurting someone, and that’s the problem. What is the most fair system right now? I think the most fair system is the system that everyone understands,” he said.

If the quest for the most fair system unites the opposing sides of the recall effort, then its answer divides them.

• Claire Stremple is a reporter based in Juneau who got her start in public radio at KHNS in Haines, and then on the health and environment beat at KTOO in Juneau. This article originally appeared online at alaskabeacon.com. Alaska Beacon, an affiliate of States Newsroom, is an independent, nonpartisan news organization focused on connecting Alaskans to their state government.