It was a tense election, one that riveted Juneau and tore it apart.

On an October night, as Juneauites gathered for a political meeting, a blast shook Front Street.

It was a bomb.

Planted in the heart of Juneau’s business district, the bomb tore apart two businesses but killed no one. It terrified the city and set it on edge.

For weeks afterward, residents wondered about its source. Who set it? Why? Was it political terrorism or a personal vendetta? Would there be others?

The answers have remained unpublished ever since the bomb detonated on the evening of Oct. 26, 1926.

“As you personally know,” wrote Juneau City Clerk H.R. Shepard a week and a half afterward, “this was probably the most dastardly crime ever committed in Alaska, not only destroying several thousand dollars worth of property situated in the very center of our business section at an hour when the city streets were filled with citizens. It still remains a mystery why a number of lives were not lost.”

No charges were ever filed, and no one was ever arrested.

Now, through a Freedom of Information Act request with the FBI, the Empire is able to publish the investigation behind Juneau’s first terrorist bombing and what likely triggered it.

As it turns out, the bombing probably wasn’t politically motivated at all; its most likely cause was a dispute between bakers.

Undercover investigation

In the days following the blast, the Juneau Police Department and the U.S. Marshals investigated but found themselves helpless. Law enforcement in remote territorial Alaska had neither the resources nor the training to investigate terrorism.

In desperation, the city council asked the federal Bureau of Investigation to step in. The bureau’s special agent in Seattle forwarded the request to Washington, D.C., where J. Edgar Hoover had become the bureau’s director only two years before. The Bureau of Investigation was still nine years from becoming the FBI, and Hoover had only finished hiring the first group of “his” men.

Among them was Hugh Wade, a young man who graduated with a law degree from the University of Iowa and moved to Nebraska, where he decided to join the bureau.

After training, he was assigned fresh to Seattle. That made him perfect to investigate the Peerless bombing, his supervisor thought.

He wrote Hoover, asking for permission: “… my idea being that Agent Wade, who has recently been assigned to this office from Omaha, Nebr., and who is entirely unknown in Juneau, could no doubt do considerable undercover work and keep in touch with the U.S. Marshal before his identity would become known.”

Hoover responded via telegraph.

“Authorization granted. Assignment Agent Wade investigation Juneau as per your letter,” he sent.

On Nov. 27, 1926, Wade boarded a steamship for Alaska, a place he had never seen.

Brawling bakeries

In the early 1920s, Juneau was a bustling but small town reliant on the Alaska-Juneau mine and smaller gold mines in the surrounding area. The 1920 census measured just over 3,000 people; the 1930 census counted just over 4,000. Those figures didn’t include Douglas or the Mendenhall Valley, which was inhabited by a few dairy farmers.

Seattle was a long steamship ride away, and the city’s first scheduled airline flight hadn’t taken off. If someone wanted fresh food, he or she had to buy it locally. Three bakeries competed for residents’ business; the biggest was Smith Brothers’; Peerless was No. 2; and trailing at No. 3 was Star.

Smith Brothers and Peerless competed with each other, but it was a friendly competition. That wasn’t the case between Peerless and Star.

In 1926, Peerless was owned by Theodore Heyder and Henry Meier. Meier had lived in Juneau for about four years, while Heyder had been in the city since 1913, always operating bakeries but usually struggling. When he partnered with Meier, his fortune began to change and the bakery began to do well.

Four years before, the two men hired a baker named Louis Lindner to work with them, but it proved to be a mistake. Lindner was paranoid and rough. At one point, he speculated to his bosses about how much dynamite it would take to blow up the city’s bank and rob it. He feared almost from the start that he would be fired — which happened in December 1922 after Lindner’s behavior worsened.

Before joining Peerless, Lindner had his own bakery, and afterward he restarted his own shop. He called it Star Bakery.

The owners of Star and Peerless were cold toward each other, but in March 1925, they turned outright hostile.

That month, Heyder traveled to Port Alexander to drum up business. There, he spoke to a woman who worked with Star, but she refused to defect. As Heyder returned to Juneau, the woman placed an order in a sealed envelope addressed to Star. She gave it to a steamship’s purser, telling him to deliver it.

Heyder also traveled on that steamship, and when it arrived in Juneau, he drove the purser to Star Bakery.

The order arrived too late for Lindner to fill it in time, but Peerless had the equipment and time. When Lindner saw his business go to his competitor, he accused Heyder of deliberately delaying the message. He filed a formal complaint with the U.S. Postal Service, and Heyder was furious.

He shouted at Lindner, threatening to expose him as a “slacker” who had dodged military service during World War I.

The bad blood ran deep.

Hugh Wade learned all of this as he worked in Juneau undercover. Only the U.S. Marshal and the local district court judge knew who he was. For more than a month, he quietly asked questions, combed rumors and interviewed suspects. He documented his investigation in regular reports sent to Seattle and forwarded to Washington, D.C.

Lindner, perennially suspicious, kept dodging questions. Shortly after Christmas, Wade changed tactics. He walked into Lindner’s store and revealed his identity.

The investigation was open.

The blast

The week before the bombing was a bad one for those who lived on the shores of Gastineau Channel. Taku winds fanned an enormous conflagration that burned down most of Douglas.

Mine workers flocked via ferry from Juneau to fight the flames without success. In desperation, firefighters blasted firebreaks with dynamite. Explosives were borrowed with haste from nearby mines. There was no recordkeeping and no accounting.

Wade, trying to track the dynamite used in the bombing, was frustrated.

“Dynamite could also be obtained from the Alaska-Juneau Mine at Juneau, as it is used daily and no check is kept on it,” he wrote.

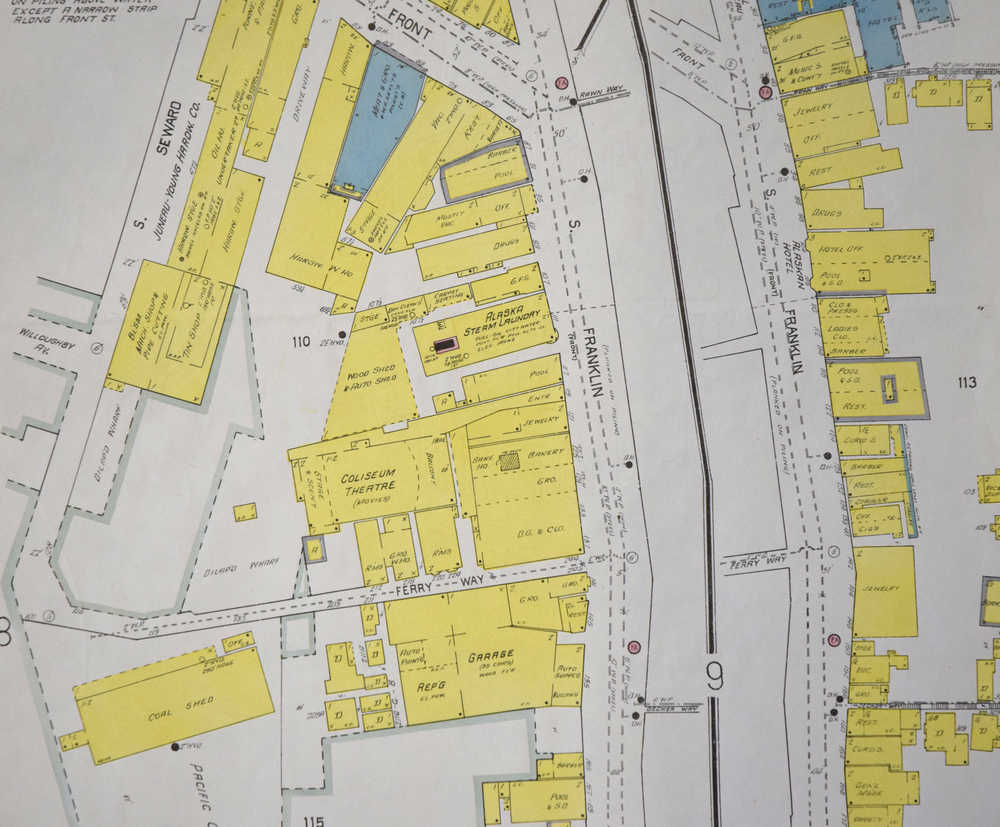

The night before the explosion, Juneau hosted a political rally by Tom Marquam, an independent candidate for Alaska’s nonvoting seat in Congress. He was the chief opposition to the incumbent, Republican Dan Sutherland. The Empire reported that 1,100 people crammed the Coliseum Theatre, which abutted Peerless Bakery.

The following night, a much smaller gathering took place in the theater as Marquam held another rally in Douglas.

“Politics around the office warm — even hot,” wrote judge James Wickersham in a diary entry from early October 1926.

“The Marquam meeting was noisy and vicious,” he noted on the morning of the bombing.

About 5:30 p.m., Henry Meier and one of the Peerless delivery boys were working in the front of the bakery when they were abruptly thrown forward and to the ground with a shock. Windows shattered around them

Billie Wright, a bystander, described to the Empire how “a blue flame shot upward through the skylight of the Peerless Bakery and she saw it through a side window.”

Investigation by the Juneau Police Department and explosives experts from the Alaska-Juneau Mine (no one in town was more skilled with dynamite) revealed the bomb had been placed underneath the Peerless Bakery.

The dynamite left a distinct smell, and there was no doubt among the miners about the cause of the blast.

At the time, South Franklin Street and every shop west of it were built on pilings above tidal flats. “The charge, it is believed, had been placed during high tide by someone apparently with malicious intent,” the Empire wrote.

The paper speculated that it would have been easy to reach the underside of the bakery via boat. At low tide, someone could have walked along the beach and — using a ladder — placed the bomb.

“The concussion following the explosion was felt over a considerable section of the city and especially on the hill sides along and above Gastineau Avenue. Many believed the rumble was caused by an explosion in the mine,” the Empire noted.

Close to the blast, there was no doubt.

The bomber had planted his explosive at an auspicious location — directly beneath the steel beam that supported Peerless’ two bakery ovens.

The ovens, heavily built of brick and steel, were nearly impervious to the blast, which blew a hole in the floor of the bakery and shattered its skylight. Despite that damage, the ovens’ bulk channeled the explosion into the building next door.

That building, a jewelry store, exploded in a spray of glass.

Windows and lights across Franklin Street broke as well.

The city’s fire department responded quickly, extinguishing the few flames started by the explosion. Police quickly roped off the area to prevent looting, and most of the jewelry was saved.

By 7 p.m., city officials and business owners were ready to begin picking up the pieces and solving the mystery.

Wade’s investigation

Once his identity was revealed, Wade began focusing on Lindner intently. He had arrived in Juneau with alternative theories, but he discarded those in the months after his arrival. The political angle — popular among Juneau residents — was the first to fall. After all, the possible target had been in Douglas at the time of the bombing.

The second theory, that Heyder or Meier blew up their own bakery as an insurance scam, was discarded when Wade learned the bakery wasn’t insured for its full value and that it had been making good money.

It had been making such good money that the owners of Peerless Bakery had invested in a new business, the Coastwise Shipping Company, which offered ferry service between Juneau, Douglas, Thane and other mining camps in the area.

Their new company, formed in June 1926, was a direct competitor with the existing Jim Davis Shipping Company, which for years had run a small boat named the Esteboth.

“Agent made inquiry and learned that several people thought that Jim Davis would do the act or have it done if he thought he could benefit by it and could get away with it,” Wade wrote on Dec. 23.

After further investigation, however, Wade ruled out Davis’ shipping company as a suspect. Many people in Juneau said Davis was bitter toward the bakery owners, but he would have realized the consequences of such a bombing and wouldn’t done it.

Among those vouching for Davis was Gov. George Parks, who “stated that he has known Jim Davis for years and has dealt with him and that Davis has not been injured to the extent of committing an act of this kind.”

That left Lindner, and in January, Wade confronted the owner of Star Bakery with everything he had learned.

Lindner speaks

For two months, Wade had collected rumors and stories about Lindner. He had spoken to acquaintances, friends and enemies alike. They painted a picture of a bitter, paranoid man, unmarried and possibly infected with a venereal disease.

“A check of the physicians of Juneau does not show that he was ever treated for such a disease,” Wade noted.

When Lindner spoke to Wade and explained himself, Lindner admitted he was familiar with explosives. He admitted he owned a boat. He admitted “that he was the type of person who would commit the crime if he thought it would benefit him, and his bakery is so located that it would be an easy matter to place the explosives under the Peerless Bakery without anyone knowing that he did it,” Wade noted.

But Lindner had an alibi. His employee, a woman named Sumner, said Lindner was working upstairs at the Star Bakery when the blast happened. “She rushed outside to see what happened, and Lindner came down and later went upstairs to his work. He did not make any remarks,” Wade reported.

The bomb could still have been set on a timer or by a switch activated by the tide, but Wade found no evidence of that.

The means, motive and opportunity all pointed to Lindner as the bomber and Peerless Bakery as the target, but the evidence was circumstantial.

“In fact, throughout the whole investigation, everything indicates that Lindner would be the logical suspect, but there is not sufficient evidence to file a complaint against Lindner,” Wade wrote on Feb. 4, 1927. “The U.S. Marshal was advised of the results of this investigation and should anything further develop, this office will be notified and further investigation can be conducted. Case closed.”

After the facts

By the time he wrote those final words, Wade had returned to Seattle. While he didn’t capture his man or make his arrest, he had caught something that would change his life — a love for Alaska.

He returned to the territory again and again, working undercover as a bond salesman, and met Madge Case. After a long-distance relationship, they married in 1933.

Wade left the Bureau of Investigation to join President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration in Alaska, and the couple returned to Juneau.

Wade was elected territorial treasurer in 1955, and he was secretary of state under Gov. Bill Egan. When Egan fell ill soon after statehood, Wade became the state’s acting governor.

He died in 1995, leaving behind a family with deep roots in Juneau.

The Peerless Bakery survived the bombing and continued to flourish. According to records kept in the Alaska State Library’s historical collections, it survived the Great Depression and World War II. In May 1945, Henry Meier sold his bakery to H.M. Sully after 23 years in business.

It lived on, renamed, as Sully’s Bakery and Juneau Bakery.

Star Bakery lived on as well, albeit under different owners. In 1930, James Sofoulis began operating a bakery by that name at a spot where the downtown library now stands.

Lindner’s fate is less clear. He does not appear in records kept by the historical library or in biographies of Juneau pioneers.

In fact, he appears to disappear from the historical record entirely, leaving behind only a bombing as his mark on Juneau history.