The owners of the Bergmann Hotel have hired an Anchorage-based consultant to help them stop the once-prestigious hotel’s descent into dereliction. Some community members — the hotel’s tenants, especially — worry what the impending changes might mean.

For more than 100 years, the Bergmann has boarded Juneau residents and travelers alike. It used to stand proudly at the top of the hill where Third and Harris streets intersect, overlooking downtown. It’s even listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

But during the past several years, the building and its status in the community have been deteriorating. Neglect and an increasingly bad reputation turned the hotel into a de facto extended stay for many Juneau residents bordering on homelessness.

When the building’s former caretaker became unable to continue his job about two weeks ago, Kahleen Barrett, the owner of the Bergmann, hired government-relations consultant David D’Amato to turn the building around. She and her son, James Barrett, also owned the twice-burned, recently demolished Gastineau Apartments.

“The Barretts are in the process of evaluating the building and the options for it, and they’re working in concert with the City and Borough of Juneau,” D’Amato told the Empire in a phone interview Friday afternoon. He had recently flown back to Anchorage after spending the week in Juneau touring the building and meeting with city officials. “We’re trying to understand how this property could fit into the vision of downtown Juneau heading into the future.”

D’Amato and the Barretts don’t yet have a plan for the building. Right now, they’re “doing a little bit of triage,” D’Amato said. He hadn’t seen the building in about 15 years until he walked through it with city officials on Wednesday. He said he remembered it when it was in its heyday. Those days have long since passed.

“It was in a different state than I had remembered, and it was very clear to me that there were vulnerable people in there,” D’Amato said.

Paradise lost

Veronica Shortcakes has been living in the Bergmann since mid December, which she was quick to say is “too long.” She and her boyfriend Timothy — who asked that his last name be omitted — live together in a room that makes most college dorm rooms seem spacious. She and Timothy sat down in their room with the me Friday morning to describe what life in the Bergman is like.

Shortcakes’ and Timothy’s room is about 10 feet by 15 feet and includes a sink and closet. When it’s working, they share a communal bathroom with the other people on their floor. But Bergmann residents have to learn not to take running water for granted. During the four and a half months that Shortcakes has lived in the hotel she said the running water has been shut off several times, sometimes for weeks at a time.

She sat surrounded by jugs of clean water while speaking with me and explained that she has to keep them full whenever the water is working because she never knows when the faucets are going to run dry.

“Every time they turn the water on, I have to fill them up or else I have to go to Rainbow Foods to buy more water,” Shortcakes said. “I believe in bird baths, but not to this extent.”

But bathing without running water is not the only problem Bergmann residents face when the water is off. Shortcakes and Timothy said that the toilets in the building’s communal bathrooms quickly become filled with human excrement without running water, filling the entire building with a horrendous odor.

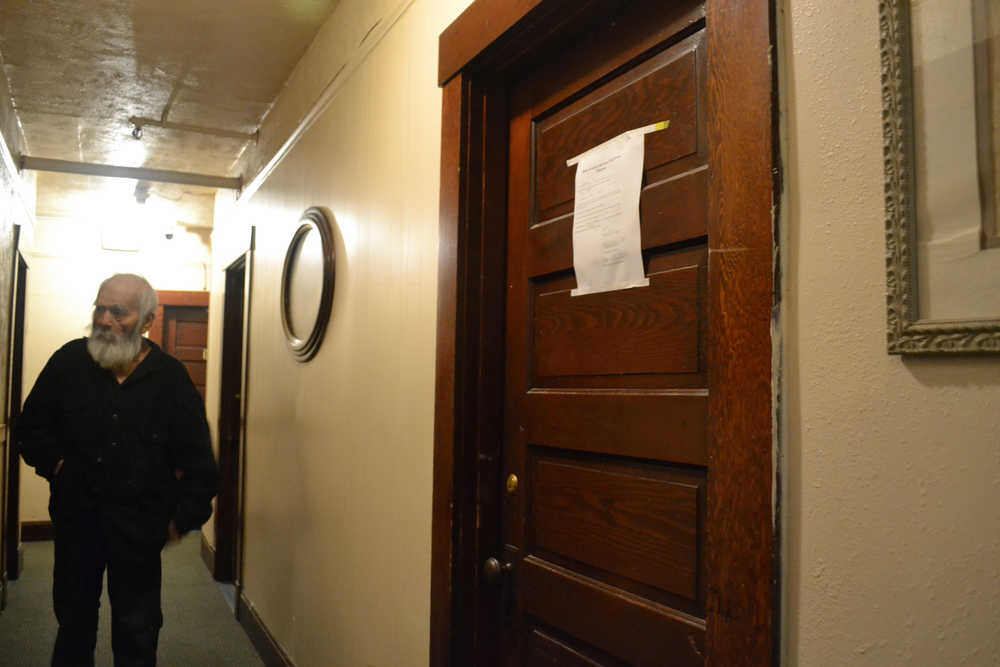

A water utility disconnect notice currently hangs from the hotel manager’s door, warning that the Bergmann’s residents will once again be without water if the owners don’t pay their past-due water bill of about $4,500 by Wednesday.

D’Amato, who is returning to Juneau on Tuesday, said that he will take care of the bill before the city shuts off the water.

“We’re going to make sure that in the interim between now and when some decisions are finally made people have all the services that they’re entitled to and that they need,” he said. “They don’t have anything to worry about with the water being shut off; we will get that in hand.”

In addition to facing water shortages and regular power outages — also a part of daily life in the Bergmann — Shortcakes and Timothy said that the hotel’s residents must adapt to life surrounded constantly by drug use and violence.

During the past four and a half months, Shortcakes said she has been assaulted twice in the building, once by the former manager, who she said sprayed her with bear spray after she opened her door to let him into her room.

Nowhere else to go

Even if the Bergmann’s other residents haven’t had it as rough as Shortcakes and Timothy — which is doubtful, considering one resident described the hotel as a “craphole” when I ran into her in the hall — the building is undeniably in a state of disrepair.

Windows and doors are boarded shut. The carpet is ripped and stained. Swastikas are carved into some of the wooden doors, and the faint smell of the bathroom situation Shortcakes described still hangs in the air.

But for many Bergmann residents, the decision to live in the Bergmann is easy. That’s because their only other option is living on the streets.

Glory Hole Director Mariya Lovishchuk walked through the building earlier this week with D’Amato. Glory Hole staff knocked on every door in the building as a part of a vulnerability audit. They found that of the hotel’s 50 or so residents, 18 are at a high risk of becoming homeless if they had to leave the Bergmann.

“A lot of those people definitely can’t be placed immediately in any other place in the community,” she said Friday morning. “It takes time to find housing because all the waiting lines are so long everywhere. We’re talking about people with extreme health issues who are very likely to die on the street.”

Shortcakes and Timothy are all too familiar with this struggle. Timothy said they have tried several times to find another place to live, but they have run into the same lines that Lovishchuk mentioned every time. Even their caseworkers have been unable to help them, Timothy said.

“I talked to my case worker, and he said, ‘No. You’re on the street.’ Point blank,” he said. “We’re on a few lists, but there’s no available apartments, and if there are, people are standing in line to get them.”

Both he and Shortcakes were homeless for three years before they moved into the Bergmann. They spent most of that time in Seattle, but they lived on the streets of Juneau for six months before they started renting their room.

Lovishchuk said that the Juneau Housing First project, which will add 44 housing units specifically for Juneau’s homeless population, could potentially house some of the Bergmann’s most vulnerable residents. The only problem is that those units won’t come online until next January when the project is complete.

Shortcakes said she plans to move back to Seattle before June, at least in part because of the wretched living conditions of the Bergmann. Timothy said he plans to leave Juneau when Shortcakes does, but he isn’t sure where he will go yet. He said he might go to Cordova, where he’s lived and worked before, or he might return to Seattle with Shortcakes. Regardless of where he ends up, he’ll be out of the Bergmann.

Hope on the horizon

Rumors travel quickly in Juneau and perhaps even more quickly in the Bergmann. Shortly after the hotel’s residents learned that the Barretts had hired D’Amato, they feared the worst. Shortcakes and Timothy thought they might be kicked out. Other residents did, too.

Though D’Amato has evicted a handful of people, he said he only removed squatters and has no plans to force any of the building’s legal residents to leave.

“Absolutely no evictions have been made for anybody who has any type of residency there,” he said. “We want to make sure that we don’t exacerbate any homelessness problem. We’re here to help, not the other way around.”

Lovishchuk corroborated this claim and said that D’Amato has made good on his word so far.

“The owner is working with us to make sure not to evict the most vulnerable people if at all possible,” she said. “They could just board it up and be done with it, and they’re not doing that.”

Though D’Amato doesn’t know what will happen to the building, he said that he plans to work closely with city officials and community members to determine an appropriate use for the hotel, perhaps even one that helps to solve the city’s housing and homelessness problems.

“I look at buildings like the Bergmann with unbridled optimism about what it could be,” he said. “But what it could be really hinges on a team effort. There’s no one person — save Richard Branson or Mark Zuckerberg — that could pull this together alone, and that might not be good anyway. The best decisions are either made or informed by the community.”

Still, such projects take a lot of time and effort, and we’re likely a ways off from seeing any big changes at the Bergmann. For the time being, most residents would probably be happy simply to see running water when the go to use their sinks.

• Contact reporter Sam DeGrave at 523-2279 or sam.degrave@juneauempire.com.