Summer, 1475 CE. Orabella, a once homeless young woman now apprenticed to the studio of Verrocchio, paints a fresco for the home of Lorenzo de Medici in the hills above the Tuscan city of Florence. She has the help of Leonardo da Vinci In the design of the work.

***

She is an orphan, a girl of the streets living in a poor section of Florence, near the industrial docks along the Arno. She does not know her parents, nor can she say with any certainty the last time she felt close to a grown man or woman, other than the young woman, a prostitute catering to the upper classes, who took her in when she was barely more than a toddler.

Their paths had crossed early one morning on Florence’s back streets, as the taverns closed, and before the shop stalls opened. The orphan had suddenly appeared beside the prostitute and taken her hand. The orphan looked up into the eyes of the prostitute who was, at first, not sure what to do with this small child. As she walked to her small but clean room after a night of entertaining the guests of her most important client, she was not at all sure she had the energy to deal with this.

After succumbing to the charm and pathos and need for decent clothes and a meal in the orphan’s eyes that morning, the prostitute — she was called Magdalene — cared for the girl, teaching her the alphabet and basic reading and writing. She often took her around to see the sights, including the statues along the major piazzi and the churches in the wealthier neighborhoods, though, thinking it wasn’t her place, she never gave the child a name.

Unfortunately, after a few years, the young prostitute grew ill and died in the orphan’s young and caring arms.

After being turned out of the comfort of the prostitute’s chambers, the orphan did not know where to turn. She had to develop intelligence, wit, and the physical and mental strength needed to survive. For a long time, her closest friends were other children of the streets. Most had the skills and toughness of the orphan, but none had her powerful desire to rise above their squalid lives. The child dreamed of rising, transformed, into the beautiful world Magdalene had exposed her to in her earliest years.

***

The girl does not have a clear memory of her former life until, one day, she and her young friends are walking along the streets toward one of the city’s cleaner public markets. She is impressed by all of the fine clothes and refined speaking of the shoppers out on this sunny day. Though it has been a few years, a vision of Magdalene crosses in front of her eyes. She has to turn away from her mates, her eyes suddenly flooded with tears. Once she composes herself, the group goes back to the important business of lifting valuables from the purses and pockets of the wealthy.

In their frequent forays into the more well-to-do parts of the city, the knowledge the girl has gained from walking tours with her now-deceased mentor become a guide to the most crowded areas, where the pickings will be particularly fruitful for her tiny band of pickpockets and petty thieves.

After a few harrowing escapes across rooftops and through back alleys, with tradesmen, servants, and armed guards in pursuit, her young friends grow to respect all that she knows that is important to their independence and well-being. She knows the wealthy neighborhoods well, and she knows how to avoid the scrutiny of the many private security guards in them, who are constantly on the lookout for ragamuffins. The girl’s friends soon begin to call her “Orabella,” which means beautiful gold.

Other than the many sweet endearments from Magdalene, Orabella is the first name the girl has ever had that she can call her own. The young street tough who first gave her the name gave it with an attitude of friendliness that she did not understand. She had shown him no special favor. The tough—his name was Carlo—was overweight, dressed poorly, had pimples and a vulgar mouth.

Even so, Orabella could not ignore the fact that Carlo seemed to have the respect of the others. He was the one who collected the day’s stolen goods and redistributed them to those who, in his judgment, had the greatest need for whichever item had been taken. Any leftovers were held by Carlo to be distributed on another day in response to a different and more urgent need.

Nobody argued about this for at least as long as Orabella had been with them.

Carlo protected her whenever any of the others tried to physically push her around or talk dirty to her or call her ugly names. When Carlo stepped into a situation involving Orabella, the others always stepped away.

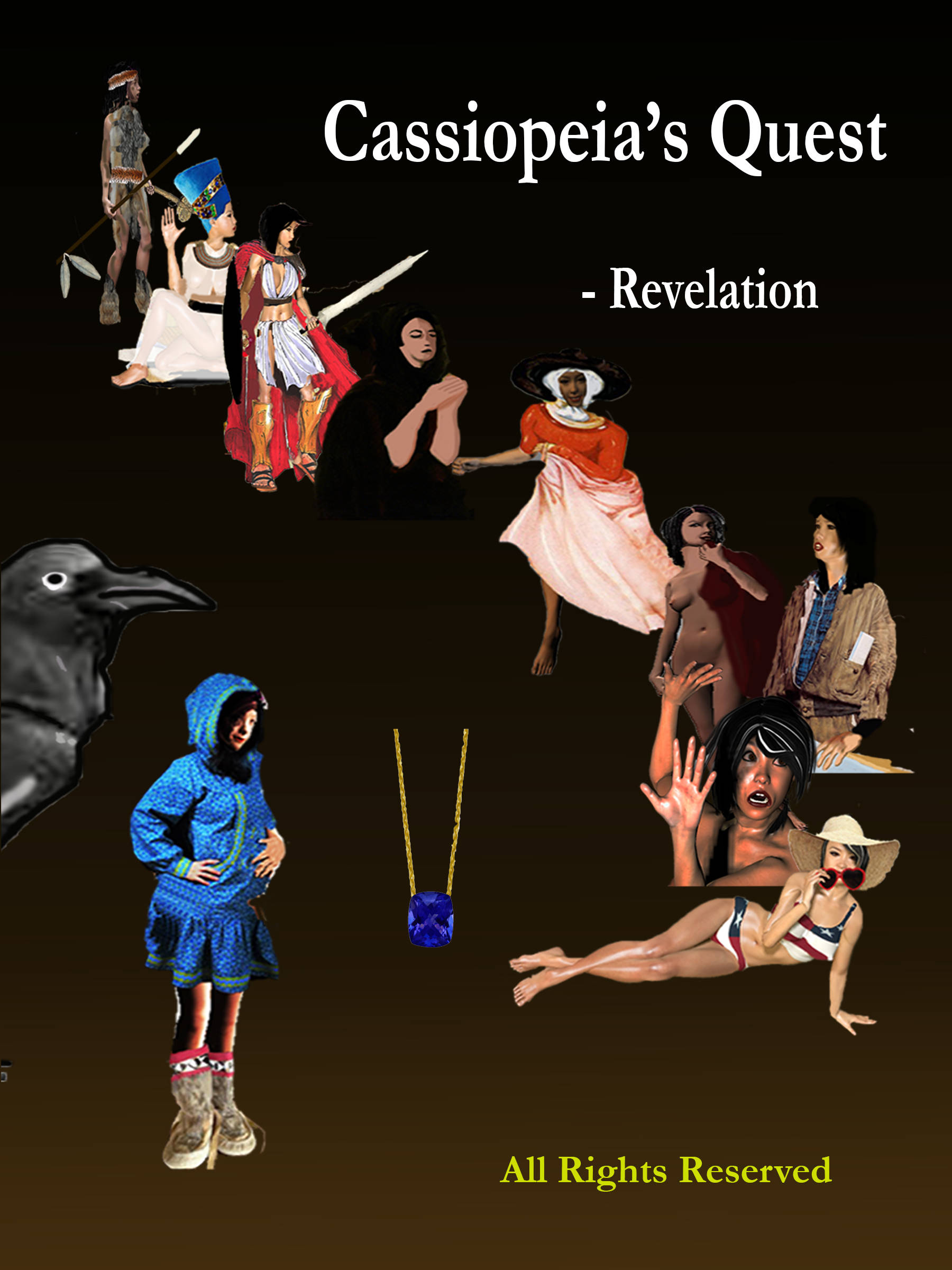

• This is an excerpt from Jerry Smetzer’s historical fiction piece “Rebirth.” It is the sixth in a collection of 10 such pieces in a collection titled “Cassiopeia’s Quest-Revelation.” The Capital City Weekly accepts submissions of poetry, fiction and nonfiction for Writers’ Weir. To submit a piece for consideration, email us at editor@juneauempire.com.