By Aaron Hamlin

As a primary voter for Alaska’s U.S. House seat, you’ll get to pick among a wide, wide array of candidates: 15 Republicans, six Democrats, four from other parties, 23 nonpartisan or undeclared candidates, one Sarah Palin, and one Santa Claus.

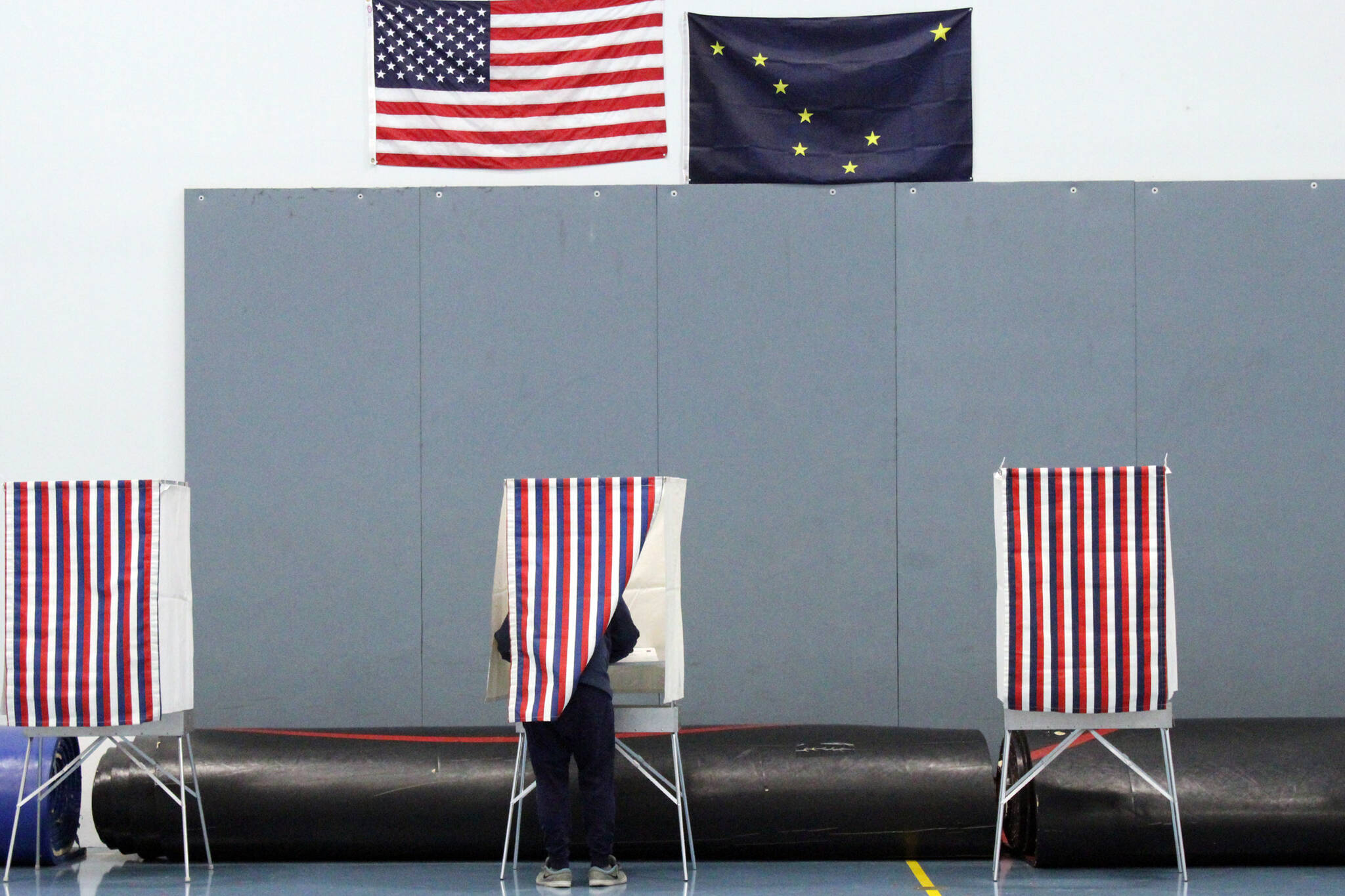

But why are Alaskan voters choosing among 48 candidates for their open House seat?

To answer that, let’s look back to 2020. There, Alaska’s voters passed a ballot initiative by 50.6% that made way for the use of top-four open primaries combined with ranked-choice voting for the general election.

Top-four open primaries mean that all the candidates, regardless of affiliation, run in the same primary. Ranked-choice voting means that in the general election, voters rank the candidates, and then the candidates are eliminated in a sort of simulated sequential runoff until a winner is chosen.

Previously, Alaska had closed primaries, where voters picked candidates from their own party. The winning candidate for each party’s primary would go to the general election where they would compete with each other and any independent candidate who entered the race.

It’s good that voters now have many options to choose from. And it’s good that independents also have a say in who makes it to the general.

So what’s the problem with having 48 candidates?

Quite simply, choosing just one of them. That’s what the ballot initiative now forces voters to do in the primary. And because four candidates advance to the general election, ranked-choice — by its own limitations — just doesn’t work well for open primaries where multiple candidates have to go to the next round. Ranked choice’s limitations are why those who designed the ballot initiative didn’t add the ranked-choice component to the primary.

So what happens when you’re forced to choose just one candidate in a field of 48 candidates? Vote splitting. And a lot of it.

That’s a problem.

Vote splitting is when similar candidates get their support divided among the same base of voters. Imagine two identical clones who are candidates in a five-person field, and let’s say 51% of voters like both of them. Yet, voters are forced to pick one. If there was just one of them, they’d have a victory. But with two of them, they each only get around a quarter of the vote. That’s the issue with two candidates that are similar. Now imagine the number of similar candidates that arise when you have a field of 48. See the problem?

The top-four candidates could each advance with just a fraction of the vote. With vote splitting this bad, it can be impossible to know whether these four candidates were really the right ones. That’s a big deal given that whoever wins this seat could end up serving Alaskans for decades.

There is, however, another way that voters can conduct their primary and avoid vote splitting. They can use approval voting. Approval voting lets voters choose as many candidates as they want. In this case, that means that voters could choose as many of the 48 candidates as they want. Then, the top-four candidates would advance.

At The Center for Election Science, we’ve done research looking at both closed and open primaries using approval voting. In both cases — in the closed 2020 Democratic primary and with an inclusive 2016 election candidate list — we found that approval voting addressed vote-splitting. The candidates’ approval voting results neatly matched up with honest assessment scores from voters. What this tells us is that approval voting shows accurate support for candidates even in a large field.

Even in the general election, Alaska isn’t out of the woods. Assuming the strongest candidate escapes the vote splitting from the choose-one primary and makes it into the general election, they still have to win in the general. And there, with ranked-choice voting, they can still be impacted by vote splitting. Because you can only rank one candidate as first, you can split first-choice preferences in the same way as you can with a choose-one ballot. If a candidate doesn’t get enough first-choice preferences, they can be wrongly eliminated.

This isn’t to say that ranked-choice voting will necessarily pick the wrong winner. In fact, many voting methods can pick the same winner in a particular election. But some voting methods have higher risks of failure—particularly in complicated scenarios. To Alaska’s credit, at least they’re not also using the traditional choose-one method in their general election. But perhaps Alaskans deserve better than what they have now given the extra complexity that ranked-choice has added.

Of course, future states don’t have to repeat this. They can consider approval voting for both the primary and general. The top four candidates would still go on to the general, and then the candidate with the most votes still wins. Letting voters pick all the candidates they support in each stage gives all the candidates a clear, transparent show of support, and without the headache.

This Alaska election will indeed be interesting — from the general to the primary, where the focus is now. So who will you pick in the primary? Will it be Palin? One of the Democrats? Santa Claus? Just remember though. You can only pick one.

Aaron Hamlin resides in Chicago and co-founded The Center for Election Science, a national, nonpartisan nonprofit focused on voting reform. , My Turns and Letters to the Editor represent the view of the author, not the view of the Juneau Empire. Have something to say? Here’s how to submit a My Turn or letter.