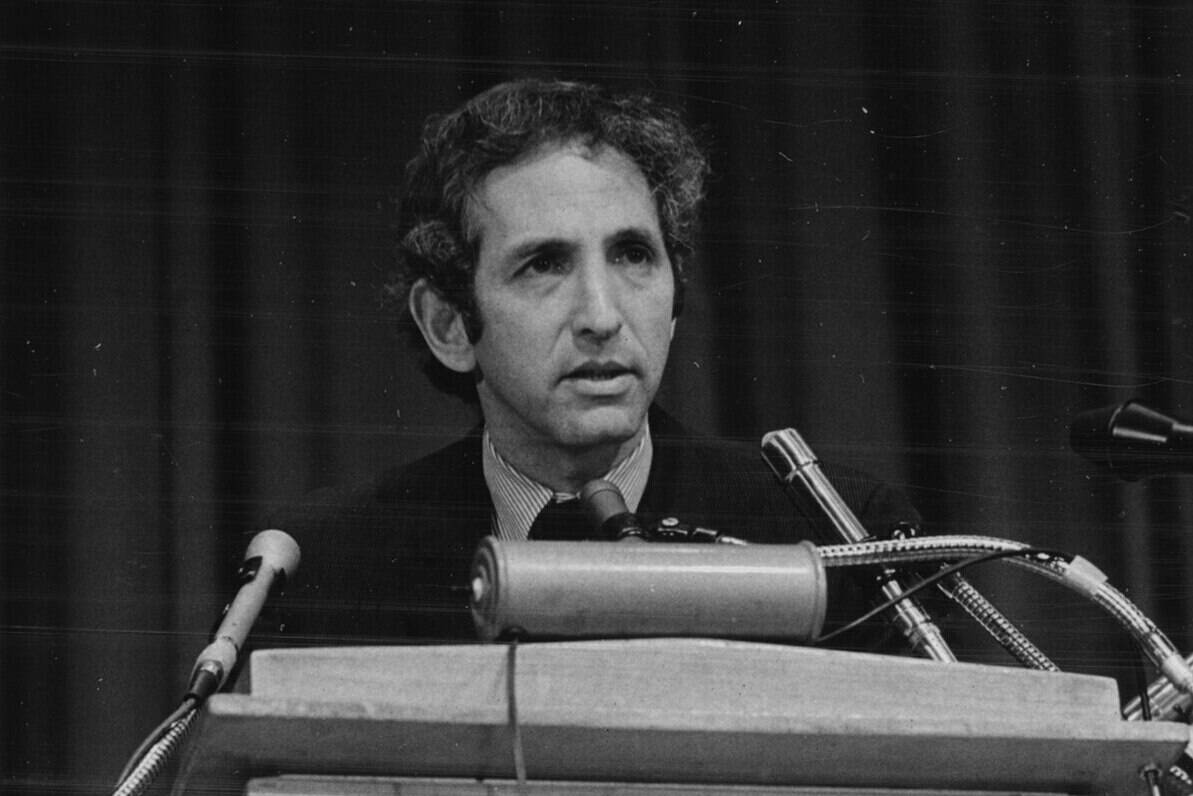

Daniel Ellsberg, known for leaking a secret study about the Vietnam war to the news media, died last week at the age of 92. The Pentagon Papers are an essential part of understanding how America got involved in the war and why we fought it in defense of the South Vietnam government for more than two decades. That’s why Ellsberg had been scheduled to speak to a class of University of Alaska Southeast students studying the history of the war.

The Pentagon Papers is the main story here. As the messenger, Ellsberg matters less than anything revealed in them. And the illegality of his deed is secondary to the sordid history of the war.

But why he chose to risk spending the rest of his life in prison is an epic battle between truth and lies that holds lessons relevant to the post-truth predicament gripping America today.

Ellsberg’s first encounter with the war was in a Pentagon task force that traveled to South Vietnam in 1961. From 1964 to 1965 he served as a high-level official under the Assistant Secretary of Defense responsible for U.S. policies related to South Vietnam. Then during two years as a State Department observer, he frequently traveled the country’s heavily mined roads and carried a weapon while on combat missions with the troops.

In 1967, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara commissioned the secret study that would become known as the Pentagon Papers. Ellsberg was one of the 31 analysts tasked with researching and writing the report. Afterwards he went back to work full time at Rand, a political think tank with high-level security clearance. They were given two copies of the final top-secret report.

According to Ellsberg’s Memoir, in May 1969 he delivered a lecture about the politics of South Vietnam to a class at the University of Ohio. That night he spent a lot of time reflecting on a specific comment he made. He told the students that most South Vietnamese didn’t care who won the war, they just wanted it to be over. A former colleague who was then working in the Nixon administration estimated eighty or ninety percent of them felt that way.

That thought tortured Ellsberg’s conscience. He began to question the legitimacy of continuing the war. Doing so “against the intense wishes of most of the inhabitants of that country began to seem to me morally wrong.”

As a supporter of the war effort, he knew he’d been protecting the false narratives McNamara and President Lyndon Johnson had presented to Congress and the American public. The Pentagon Papers revealed others had done the same thing during three prior administrations.

Ellsberg decided that continued complicity with that system was worse than the risk of a life sentence for violating the Espionage Act. After weeks of sneaking the documents out of his office at Rand to make copies, he gave some to a few members of Congress who had been critical of the war. When they did nothing, he leaked 43 of its 47 volumes to a reporter at The New York Times. They began publishing it in June 1971. Ellsberg took full responsibility for the leak.

That’s an incredibly brief synopsis of the story. Why he wasn’t convicted and sent to prison is a long sequel to it.

Few if any of us will ever be faced with taking such monumental risks with our freedom. But that doesn’t mean we’re never put in a position of choosing between defending the truth or implicitly endorsing a falsehood by looking the other way.

One problem in our digital age is the sheer volume of information we receive can make it difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction. Another is the ease with which confirmation bias has usurped the civic responsibility to discern the truth ourselves.

As George Orwell warns us in his classic dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, both are training grounds for a world in which verifiable truths no longer matter. If that happens, freedom will be reduced to an illusion.

Ellsberg’s story should be an inspiration to do better. He risked it all to reveal the truth. It became his personal salvation. Collectively following his model might help us heal our floundering democracy.

• Rich Moniak is a Juneau resident and retired civil engineer with more than 25 years of experience working in the public sector. Columns, My Turns and Letters to the Editor represent the view of the author, not the view of the Juneau Empire. Have something to say? Here’s how to submit a My Turn or letter.