By Rich Moniak

Last week, the state Supreme Court unanimously ruled the Alaska Redistricting Board’s “Senate K pairing of house districts constituted an unconstitutional political gerrymander.” What that means is the Republican majority on the Redistricting Board got caught manipulating demographic data to unjustly inflate the party’s legislative advantage for the next ten years.

Or, as is said in cases of accounting fraud, they tried to cook the books.

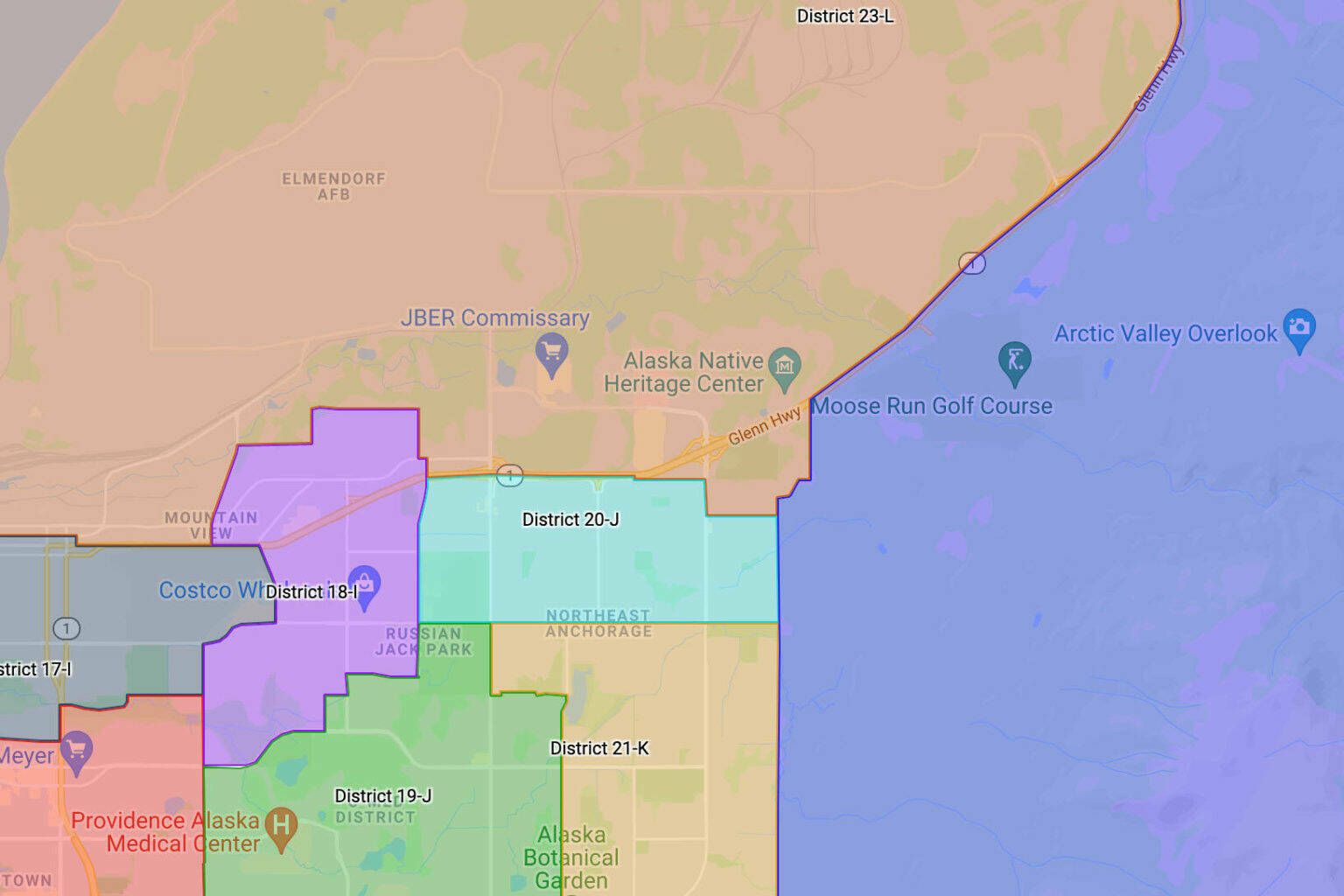

This attempt didn’t follow the more common type of gerrymandering. That’s where partisans draw district boundaries in all sorts of strange shapes to gain electoral advantages for their party. What happened here is Senate District K was formed by combining one of the two Eagle River House districts with one of the two Muldoon districts in Anchorage that shared a straight-line boundary.

The intent, however, was clearly the same.

In response to a question about why the two Eagle River districts weren’t combined with each other, Redistricting Board member Bethany Marcum said “This actually gives Eagle River the opportunity to have more representation.” Unsaid was making Eagle River residents the dominant voting bloc in two senate districts would likely result in Republicans winning an additional seat.

The three Redistricting Board members appointed by Republicans supported that plan. The other two called it “naked partisan gerrymandering.”

Marcum’s statement became a primary piece of evidence in court and is reminiscent of a case in North Carolina.

In 2016, Republican Rep. David Lewis chaired the House’s Redistricting Committee. After years of battling lawsuits filed federal court, he proposed redrawing “the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and three Democrats” but only because he didn’t “believe it’s possible to draw a map” giving Republicans the advantage in 11 districts.

That map produced the exact results he wanted. But it didn’t match the statewide election tally. Voters supported Republican candidates by a margin of 53.4%-46.6%, not the 77-23 margin of the 10-3 outcome.

Three years later, Lewis and his Senate counterpart wrote in an Atlantic article that people needed to “understand the full story, because reaching conclusions based on one spoken sentence is rarely justified and never prudent.” They briefly explained the long litigation history and argued that because federal courts and the U.S. Supreme Court recognize “political considerations are fair game,” gerrymandered maps “produced on the basis of those considerations are perfectly legal.”

To voters in North Carolina, that means legally undemocratic.

Republicans aren’t the only ones cooking the redistricting books. A Maryland judge recently rejected the state’s new congressional map approved by Democrats as being an “extreme gerrymander.” While only 64.8% of Marylanders voted for congressional Democratic candidates in 2020, maps were drawn to guarantee them victories in seven of the eight districts.

That wasn’t their first attempt. In 2017, Democratic Gov. Martin O’Malley admitted under oath that part of the redistricting intent in 2011 “was to create a map that, all things being legal and equal, would, nonetheless, be more likely to elect more Democrats rather than less.”

Republicans in Texas are the worst offenders. Not because their gerrymandered map doubled their 10-point voting edge in 2020. Rather, it leaves the state with only one district that’s up for grabs. And a system where one party or the other is all but guaranteed an electoral victory diminishes the value of voting.

That may be what the U.S. Supreme Court meant in 2019 when it issued its final ruling in the North Carolina case. They called gerrymandering “unjust” and “incompatible with democratic principles.” But they also passed the problem off to state legislatures and courts by concluding they are “political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.”

The Republicans on the Alaska Redistricting Board didn’t seem to get either message. Their Senate K district prioritized the party’s electoral goals over democratic principles. And according to Midnight Sun reporter Matt Buxton, their attorney defended it by arguing “redistricting is an inherently political process” and “anything short of a full declaration of intent cannot be reviewed by the courts.”

Alaska’s Supreme Court justices were predictably unimpressed.

Republicans have had a powerful grip on Alaska’s politics for decades. That they think cooking the books is necessary to build a bigger legislative majority suggests they know many Alaskans are justifiably unimpressed with what they’ve accomplished.

• Rich Moniak is a Juneau resident and retired civil engineer with more than 25 years of experience working in the public sector. Columns, My Turns and Letters to the Editor represent the view of the author, not the view of the Juneau Empire. Have something to say? Here’s how to submit a My Turn or letter.