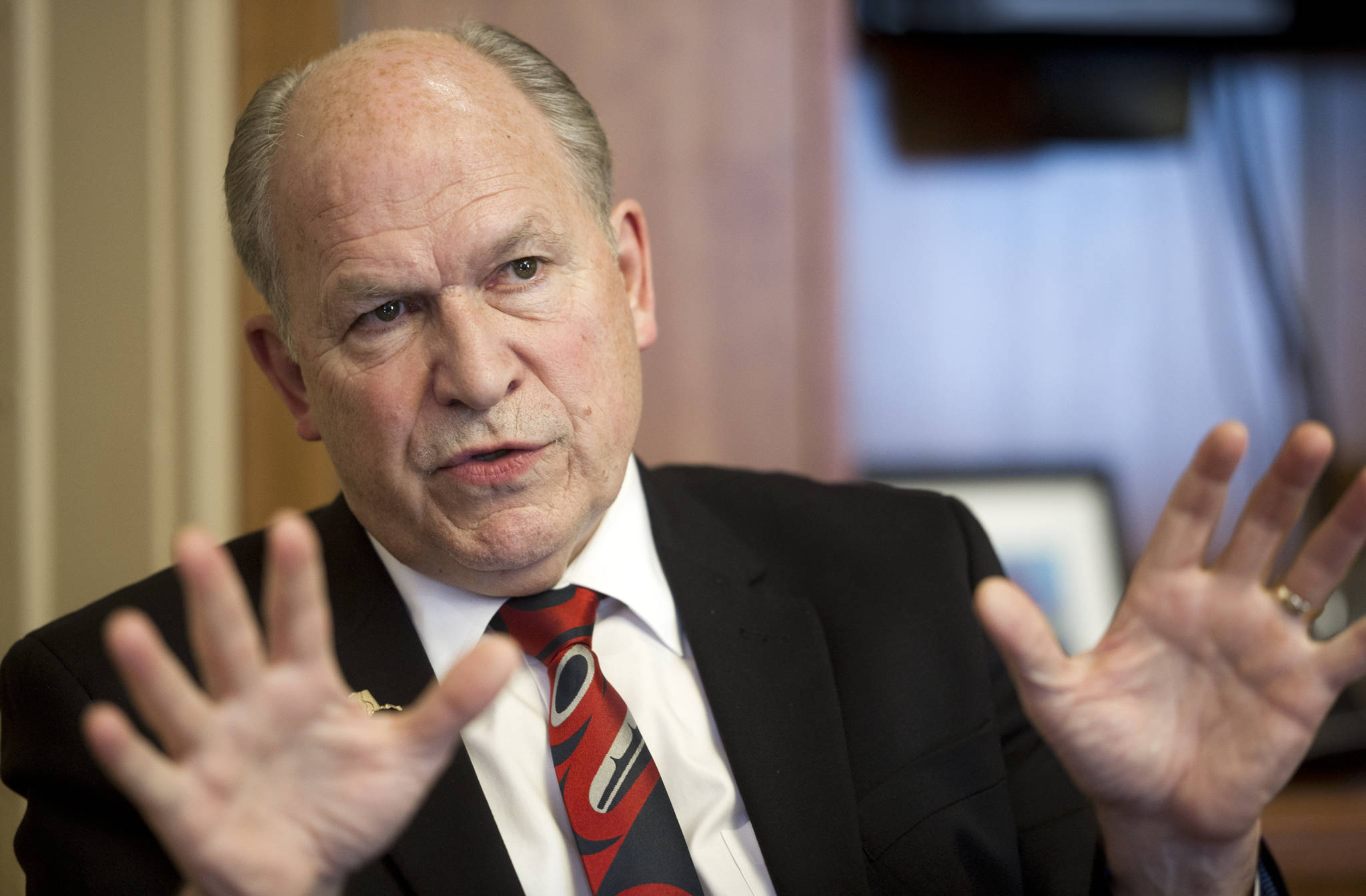

Like only one other governor before him, Bill Walker embodied the true spirit of the last frontier. It’s why he believed that Alaskans working together would “make constructive changes” to “the traditional ways of doing business” and right our financial ship of state. That he couldn’t make it happen may be a collective failure originating in our greater attachment to the nation than to the place we call home.

Much of Walker’s inspiration comes from his memory of the 1964 earthquake. He wasn’t quite 13 years old when a massive tsunami leveled his hometown of Valdez. Of the 555 people who resided there, more than 30 died. As Walker tells it, “Alaskans pulled together to bury our loved ones, rebuild our communities and forge a path forward for our state.”

Another formative experience that helped implant a deep love for Alaska in Walker was the 1967 flood in Fairbanks. Using what he learned from the earthquake recovery, he drove almost 400 miles on gravel highways to bring aid to friends living there.

Bill Egan had a similar adversity-based attachment to this place. Born in Valdez in 1914, he graduated from high school there at the start of the Great Depression. In 1940, he won a seat in the Territorial House of Representatives. He was then chosen to lead the Alaska Constitutional Convention. “We love our great United States of America” he said at the time, adding “our hearts belong to our great Territory of Alaska, and we will never have true peace of mind until we are taken in full membership as one of the great states of the Union.”

Egan and Walker aren’t the only governors who knew Alaska as a territory and watched it rebuild from the earthquake. But they’re the only two born here. And if you take Alaska out of their identities, both might have difficulty recognizing themselves as Americans.

In a recent piece titled “Yes, I’m an American Nationalist,” New York Times columnist David Brooks offers the opposite assessment of himself. “If you took America out of my identity” he writes, “I’d be unrecognizable to myself.” Because, he says, his attachment to nation is stronger than the Lower Manhattan neighborhood where he and five generations of his family had lived.

According to Brooks, this healthy form of American nationalism exists when millions “sacrifice, in sometimes opposite ways, for the common good.” It’s an “expanding love because it is love for the whole people. It’s an ennobling love because it comes with the urge to hospitality — to share what you love and to want to make more love by extending it to others.”

Implied by expanding and extending is the place where it’s all rooted. For Egan and Walker, it was Alaska when it was truly the last frontier.

That’s the spirit Walker expected would move Alaskans to pull together and solve our fiscal problems. He thought, for the sake of local economies, we’d be willing to sacrifice the nickels and dimes on the dollar saved when shopping outside. He believed we could give local farmers and fishers a boost by ending the dependence on imports for 95 percent of our food.

To varying degrees, the four governors who came here before statehood knew the Alaska Walker loves. But, like the rest, they were deeply rooted in the whole of America before they attached themselves to this place.

And it’s no different for either of the two candidates hoping to succeed Walker. Mark Begich was born in Anchorage a few years after statehood, so one might imagine he’s more Alaskan than Mike Dunleavy, who moved here from Pennsylvania in 1983. But Begich is no less American, especially with a father who was elected to Congress when he was 8 years old and having served in the U.S. Senate himself.

I’m not suggesting that either are less qualified or capable of governing Alaska. But our future will likely be determined less by the frontier spirit Walker knew than the notion of American exceptionalism; by less of community expanding out toward others than a than an inward-looking call to rugged individualism. And I’m afraid it might be a very long time before we have another governor who knows in his heart what it means to be Alaskan first.

• Rich Moniak is a Juneau resident and retired civil engineer with more than 25 years of experience working in the public sector. He contributes a weekly “My Turn” to the Juneau Empire. My Turns and Letters to the Editor represent the view of the author, not the view of the Juneau Empire.