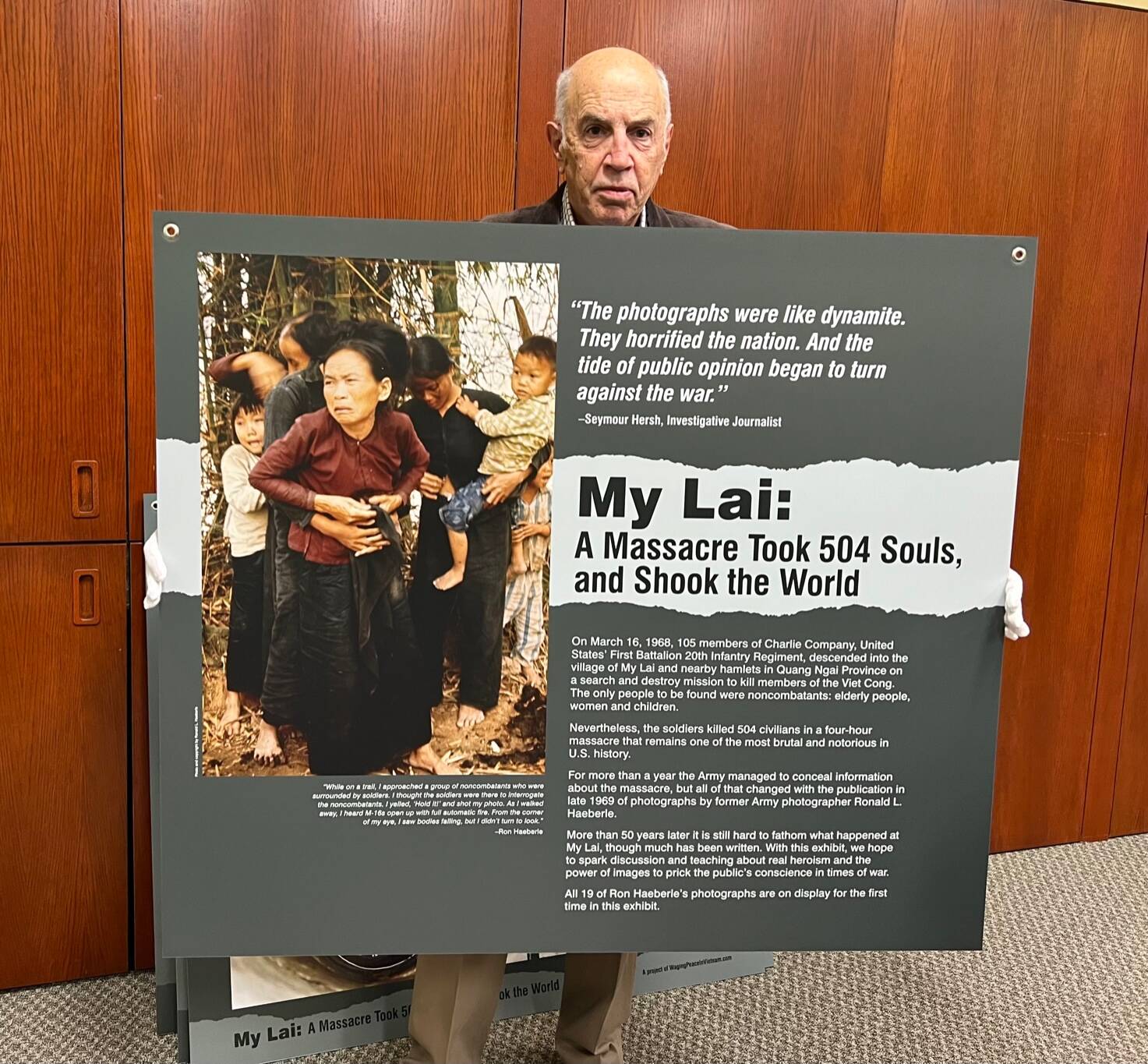

The title of the exhibit is anything but inspiring: “Mỹ Lai – A Massacre Took 504 Souls, and Shook the World.” But as is often the case, real heroes emerge from horrific events. And exhibit curator Ron Carver designed it to progress from gruesome images to the soldiers who courageously intervened. And to those who made sure America and the world learned the truth.

Mỹ Lai is one of Carver’s “Waging Peace in Vietnam” exhibits on display at the University of Alaska Southeast through Dec. 15. “U.S. Soldiers and Veterans Who Opposed the War” is the other.

In designing both, he seeks to honor soldiers whose actions challenged the war’s objectives and execution. The difference though is Mỹ Lai has been an acknowledged stain on American history for more than half a century. And the size and impact of the active GI resistance in Vietnam and on U.S. military bases is virtually unknown.

Only a few books have been written about it. “Soldiers in Revolt” was published in 1975, “A Matter of Conscience” in 1992. Authors David Cortright and William Short were both soldiers active in the movement.

Hugh Thompson Jr. wasn’t part of it when the Mỹ Lai massacre occurred. He was the pilot who saw what was happening from the air, landed his helicopter, and safely evacuated two groups of civilians.

Ron Haeberle was the army photographer assigned to the unit that committed the atrocity. His personal camera contained evidence that most of dead were women and children.

For 20 months though, their eyewitness accounts were buried under the official military narrative that claimed the unit had “killed 128 Communists in a bloody day-long battle.”

Ron Ridenhour helped expose that lie. He was the soldier most responsible for providing evidence to Seymour Hersch, the investigative journalist who broke the story. Soon afterwards, Life Magazine published Haeberle’s graphic photographs.

One reason for the military’s attempted coverup then became immediately clear. The truth about Mỹ Lai helped turn public opinion against the war.

It also infused the resistance within the military with urgency and credibility.

Before he began his work six years ago, Carver realized that “most historians in this country did not know that there was a robust GI peace movement” that contributed to bringing the war to an end. That’s why his second goal is to “change the way scholars teach about the war.”

Learning from the past requires an examination of an honest and complete history. It also necessitates trying to imagine different possible outcomes. And that requires students consider the resisters’ case against the war.

And it’s not just the Vietnam War where we should wonder about the presence and potential impact of such resistance.

“What can we learn from Germany?” Clint Smith asked in an article for the Atlantic this week. He was looking for answers to help us “memorialize the sins of our history.”

The American sin he referred to was slavery, not the Vietnam War. But in looking to Germany, he saw efforts to dedicate memorials to the millions of innocent people slaughtered by Hitler. And it’s appropriate for the world to wonder how many lives might have been saved if his Wehrmacht had been hampered by robust resistance among its enlisted personnel and officer corps.

After two trips to Berlin and the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site, Smith concluded that no memorial project, “whether in the U.S. or Germany, can ever be commensurate with the history they are tasked with remembering.” But it’s “the very act of attempting to remember that becomes the most powerful memorial of all.”

The Mỹ Lai exhibit is that kind of memorial.

Remembering the entirety of the Vietnam War is a more complex task. To be complete, we must make an effort to understand why so many active-duty soldiers risked being sent to military prison for acts of resistance. Through samplings from historical records that include GI demonstrations, petitions, and the hundreds of antiwar newspapers they published, the second exhibit shines a light on their stories.

Finally, both exhibits have a forward looking objective. By showcasing how these soldiers helped end an unjust war, Carver hopes to inspire younger generations to recognize that the possibility exists for them “to change things in our society even when it seems near hopeless.”

• Rich Moniak is a Juneau resident and retired civil engineer with more than 25 years of experience working in the public sector. Columns, My Turns and Letters to the Editor represent the view of the author, not the view of the Juneau Empire. Have something to say? Here’s how to submit a My Turn or letter.