As the first African-American quarterback inducted to the NFL Hall of Fame — and the middle child of seven from a single-parent home — the only thing ever handed to Warren Moon was a football.

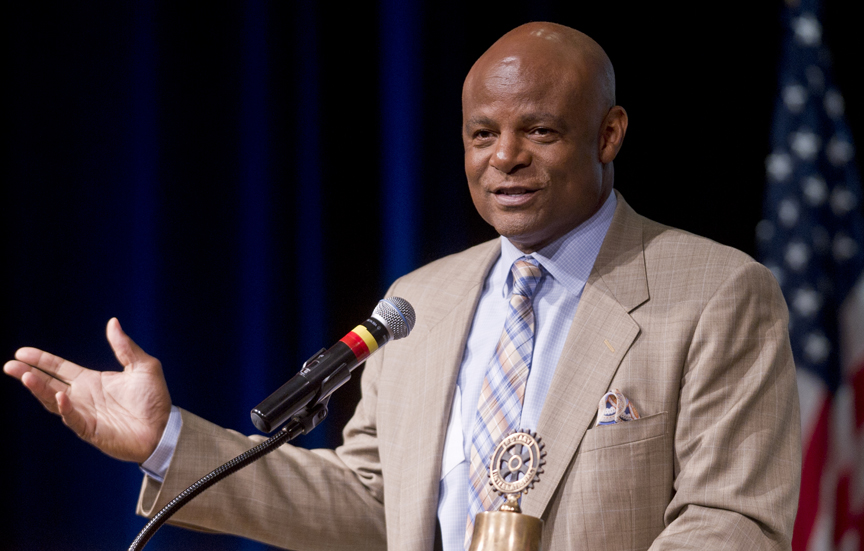

Moon delivered the keynote speech at Glacier Valley Rotary’s Pillars of America series at Centennial Hall on Wednesday.

Once he was the NFL’s highest-paid QB, and well worth the price; in 17 seasons he accumulated nine pro bowls, three all-pro nominations, 291 touchdowns and 49,325 yards. He’s one of only two players (the other being Doug Flutie) to be inducted into both the NFL and Canadian Football League halls of fame.

Though Moon is grateful for all the success in his playing career, the only thing he ever wanted was an opportunity.

“I think that’s what we all look for. … Everyone deserves an opportunity to do what we want to do in life. If you’re not good enough, then you can move on, but to not get the opportunity, that makes you so bitter,” Moon told the crowd of Rotarians and Juneau students.

Just finding the opportunity to keep playing quarterback turned out to be the biggest challenge of his career.

“As I went forward trying to become an African-American quarterback, in a time where stereotypes were used about us, I knew it was going to be a journey,” he said. “But I was determined to make it happen because I just felt I was good enough.”

Moon began his stellar career at Alexander Hamilton High School in Los Angeles, using a fake address to attend the better-funded school. Held back by racist stereotypes, Moon faced disbelievers at every stage in his career.

“It was tough for me to make the sophomore team in high school because the coach didn’t believe in African-Americans playing the quarterback position. Believe it or not, I was the third-string QB,” Moon remembers. “I went on to be an all-city and all-state quarterback. I thought I was going to get recruited by major universities, and it just wasn’t happening for me. Most schools wanted me to play a different position. They wanted me to go to defensive back, wanted me to go to wide receiver, positions I had never played before. And here I am, I’m qualified, I’m an all-city, all-state quarterback and I am being denied the opportunity to play at the next level. A lot of it was because of those stereotypes that African-American quarterbacks are guys who probably can’t lead, they probably can’t think and make decisions.”

Moon’s father died of alcoholism when he was 7, challenging his mother to raise him and his six sisters on her own. The death of his father made Moon grow up quickly and develop leadership abilities that would be called into question by ignorant coaches and fans the rest of his life.

Living with a big family helped him become an independent man, Moon said. He came out of his childhood home ready to take care of himself in every respect, something he credits to his mother, whom he calls the “most influential and inspiring person in my life.”

After playing two years at a junior college, Moon was recruited by the University of Washington, where some of UW’s own fans would boo him as he came on the field.

“The booing, the name-calling, the things that were being suggested to me. A lot of my friends in the stands got into either arguments or fisticuffs with people because of the names people were calling me. It was a lot for an 18-, 19-year-old to go through,” Moon said of his college years. “Every time I would go from the sideline to the huddle, all you would hear was boos. To walk into that huddle and the crowd is just booing like crazy, and to have those 10 guys look at you in your eyes and see that this doesn’t bother you. … It was killing me inside but I had to let these guys know in my eyes that I am confident, that we’re going to go down the field and score.”

Even after Moon proved his worth as a college QB, NFL coaches still pressured him to switch positions. Moon wouldn’t give in to the pressure — he always knew he was good enough — and after his collegiate career, which included a 1978 Rose Bowl MVP, Moon signed a contract with the Edmonton Eskimos in Alberta, Canada, where he led the team to five championships in six seasons.

Canada was a friendly place for African-American quarterbacks.

“Going to Canada, I never felt that feeling at all,” Moon said of the lack of racism from Canadian fans. “Of course, on the road you’re going to get booed from time to time, but they’re doing that because they don’t like your team, it’s nothing to do with me personally. I enjoyed playing that way because it was just about football.”

Though Moon found the acceptance and success he wanted in Canada, the challenge of the NFL was always in the back of his mind. When NFL teams finally did come knocking, he was the most sought-after player in the league.

“Now they wanted my services, so they started recruiting me, and I made them pay, I tell you, I made them pay up,” Moon said. “I wasn’t going to make it easy. … I wanted them to wine and dine me, I wanted to see the city, meet all the dignitaries. … Here’s a guy they didn’t even want to play quarterback, and now he’s the highest-paid player in the league.”

Moon went on, of course, to 17 great seasons with five different NFL teams.

He hopes people see his experience as a testament to perseverance and self-belief.

“We’re all going to get knocked down,” Moon told the Pillars audience. “What are you going to do about it?”

• Contact Sports editor Kevin Gullufsen at kevin.gullufsen@juneauempire.com or 523-2228.

Related stories: