Laurie Hernandez keeps insisting she’s too young to know better. That she’s so new to this whole Olympics thing, she doesn’t know she’s supposed to be scared.

“You just kind of have to act naive to it,” the 16-year-old said with a shrug. “It’s just another meet. The arena is just a little bigger than usual.”

The stakes, too. Yet the youngest member of the powerhouse U.S. Olympic women’s gymnastics team hardly seems intimidated. Hernandez is too busy putting on a show, her effortless charisma and “dare you to look away” performance during last week’s Olympic trials erased whatever doubt remained in national team coordinator Martha Karolyi’s mind about Hernandez’s ability to handle the big stage.

If anything, Hernandez is trying to own it. Ask her what she considers her biggest talent and she doesn’t point to any particular physical attribute but something decidedly more abstract.

“I’m confident,” she said. “I’m a crowd pleaser.”

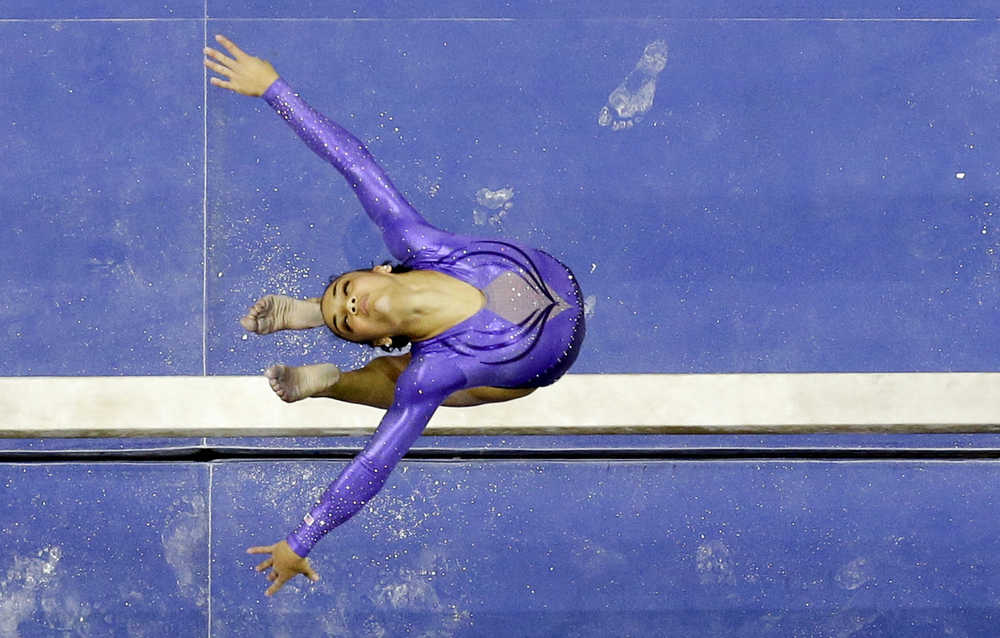

It shows, particularly when Hernandez’s floor music starts. What follows is 90 seconds of attitude and athleticism. Hernandez doesn’t dance so much as strut, every move joined by an electric smile that doesn’t seem plastered in place but an organic byproduct of the joy she’s feeling. She’s having a good time out there. And she wants you to notice.

Hernandez describes her gymnastics as “sassy” but that’s underplaying it. Her tumbling is on par with anyone on the planet not named Simone Biles — the three-time world champion who is the heavy favorite to come back from Rio with a luggage full of gold medals — and her steady, detailed work on balance beam the result of thousands of hours spent with longtime coach Maggie Haney trying to get over a small bit of stage fright.

No, really.

Hernandez admits there was a time early on she was scared of the beam. When she hopped on she’d settle into a squat because she couldn’t summon the courage to stand. Haney didn’t baby Hernandez to get her going. If anything, Haney went the other way, putting Hernandez through countless “pressure sets” designed to force Hernandez into a choice: get mentally tough or find something else to do with your free time.

Sometimes Haney would play Hernandez and teammate Jazmyn Foberg against each other, the difficulty of Foberg’s next routine based on the quality of Hernandez’s. The worst for Hernandez, however, is when Haney would tell all the kids in the gym to stop working and gather around the beam, while her star student tried to hold it together in the stillness.

“I was like, ‘Why are you doing this to me? It’s so annoying, you’re really really making me anxious,’” said Hernandez, who easily posted the top score on beam at the trials. “But then I look back and I can only thank her for that because it’s made me so calm today.”

A place that slowly came into focus over the last four years as Hernandez learned to harness her considerable talents. She rose from 21st in junior nationals in 2012 to junior champion last summer despite wrist and knee injuries that sidelined her for most of 2014. When a knee sprain threatened to derail Hernandez’s momentum this year, Haney offered a very brief, very pointed pep talk.

“I looked at her, ‘It is time. Now,’” Haney said. “She snapped and went into kind of crazy … mode. Every practice, every time on the floor was important to her.”

The eye-opener came at the Pacific Rim Championships in April, when she came in third behind Biles and three-time Olympic medalist Aly Raisman. It wasn’t just the praise from Karolyi that she noticed — it was the way people seemed to respond to her.

“You hear cheering and clapping and you’re thinking ‘I don’t even know these people,’” she said. “It brings a lot of energy, a lot of positive energy.”

Energy that practically radiates off Hernandez, the youngest of Wanda and Marcus Hernandez’s three children. A second-generation Puerto Rican, Hernandez is proud of her heritage and aware she’s suddenly become a role model, even if she doesn’t quite consider herself one.

“I think people are people,” she said. “If you want something, go get it. I don’t think it matters what race you are.”

Hernandez considers herself a gymnast above all else. Sure that smile makes it look easy, but it’s also hard earned from years and years of falling and picking herself back up. Don’t let her playful demeanor fool you; she may be the bubbliest workaholic around. She’s home-schooled and spends most days working out with Haney at one of the two gyms near her home in Old Bridge, New Jersey, about an hour south of New York City. Pressed if she has friends outside the gym, she laughs and says not really.

That’s changing by the day. Biles considers her “a little sister.” Twitter verified her account (@lzhernandez02) after the trials. The mayor of Old Bridge threw a party for her this week. Everyone is looking to come up with a good nickname. The leaders are “The Human Emoji” and “Baby Shakira.” She can’t help but laugh at the idea while simultaneously trying not to get ahead of herself.

As for college, she has verbally committed to competing at Florida whenever she’s out of high school (she still has at least two years left). She downplayed the idea of turning professional even as NBC cameras tripped over themselves following her every move at the trials. Hernandez won’t decide until after Rio so there won’t be any distractions.

“It’s all happening really fast,” she said. “This is a really cool part of my life.”