Cow parsnip is known in our field guides as Heracleum lanatum, although it sometimes has other names. The flowers are typically displayed in big, flattish inflorescences called “umbels,” each umbel comprised of several small “umbelets.” On each umbelet, the outer ring of flowers has larger petals than the others. The literature says that some flowers are strictly male, while others are hermaphroditic. Those outer flowers seem to mature ahead of the others and often lose their stamens, so they appear to be female, but really they were both male and female. Most flowers are small, only a few millimeters across, but they offer pollen and nectar to insect visitors.

At times, nothing seems to be happening on those big inflorescences, but at other times it is possible to watch the insects as they visit the flowers. I recently strolled with a friend up along Montana Creek and things were happening on cow parsnip inflorescences (which flowered later here than in other places, where the plant is already producing fruits). Some on the inflorescences were covered with dozens of flies of various sizes, from vanishingly small to the size of house flies. I have no idea who they were (except for a few hoverflies) and some of them were orange rather than blackish. We also saw a few tiny beetles, small brown moths, and a small black and white moth. Most of those visitors were sipping nectar, and maybe eating pollen, moving from flower to flower. At least some of those insects are surely pollinators, as they are for closely related plants.

Of special interest were several inflorescences with bumblebees (also potential pollinators); one inflorescence had five of those bees. The bees were very quiet, hardly moving, but they weren’t dead. Looking closely, we could usually see antennae waving or mouthparts extending to obtain nectar. A few bees were so quiet that we wondered if they were alive, but a gentle touch with a grass stem elicited a response; they were just resting. There weren’t many other kinds of open flowers along the roadway, aside from buttercups (which show no insect activity), and I wondered if these bees were driven to find some food on the tiny flowers of cow parsnip.

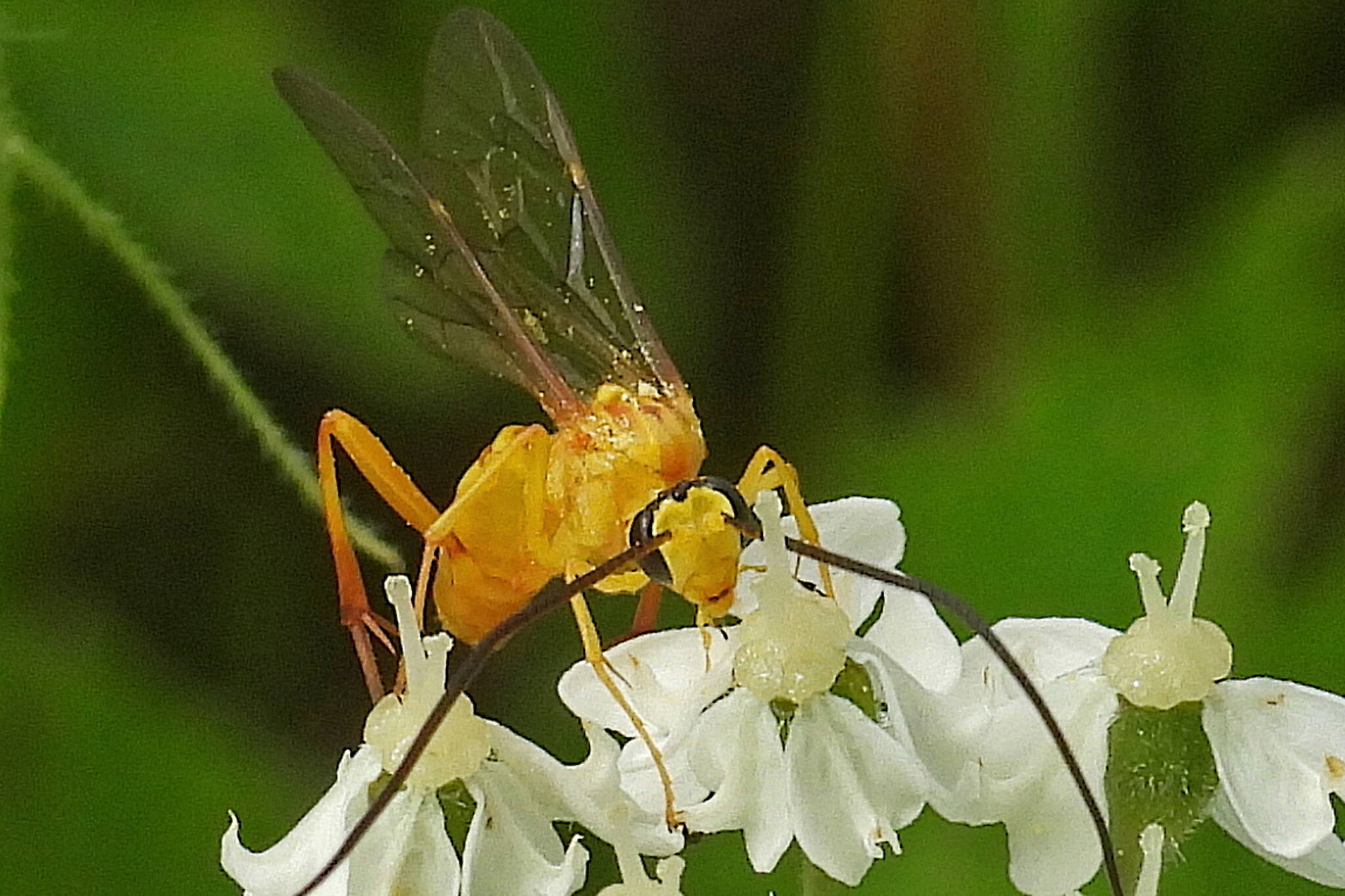

We looked carefully at the aggregations of insects to see if they interacted in some way. In the past, we have sometimes seen predatory wasps acting (deceitfully) like nectar foragers but, instead, sidling up to an unsuspecting fly and pouncing on it. But that we did not see on this particular day. However, sometimes wasps (with or without predatory intentions) do forage for nectar. For another time, it would be interesting to look at the inflorescences at night, to see who visits then.

Cow parsnip and many of its relatives produce powerful chemical substances as protection. The best known are furanocoumarins, which seem to defend the plant against fungi and perhaps other consumers. Despite the chemical defenses, bears and grazing mammals are reported to eat the plant. The amount and concentration of furanocoumarins depends in part on light and nutrients, and in some cases they are induced by herbivore attacks. Some insects have evolved the means of coping with the defensive substances and use cow parsnip as host plants for their larvae; that is so for some swallowtail butterflies and a number of types of moth, including the parsnip webworm and a stem borer.

As local hikers may know or at least learn about quickly, the sap of cow parsnip can raise big itchy, sore patches if it get on the skin and is exposed to sunlight. The defensive chemicals are phototoxic, so walkers are advised to avoid getting the sap on their exposed skin.

• Mary F. Willson is a retired professor of ecology. “On The Trails” appears every Wednesday in the Juneau Empire.